JAWA 402-CC GELANDESPORT

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

A Tough Big-Bore Endurance Machine, Wrapped in a Banana

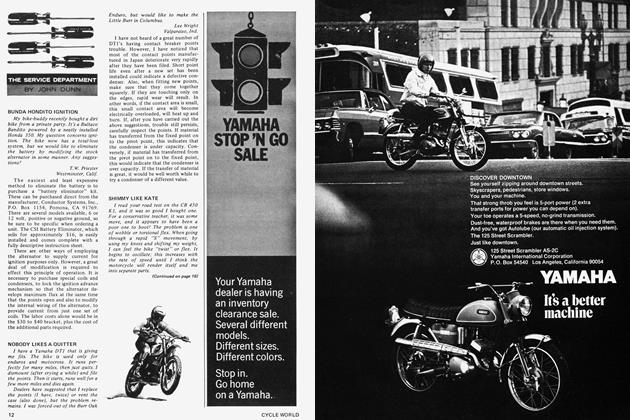

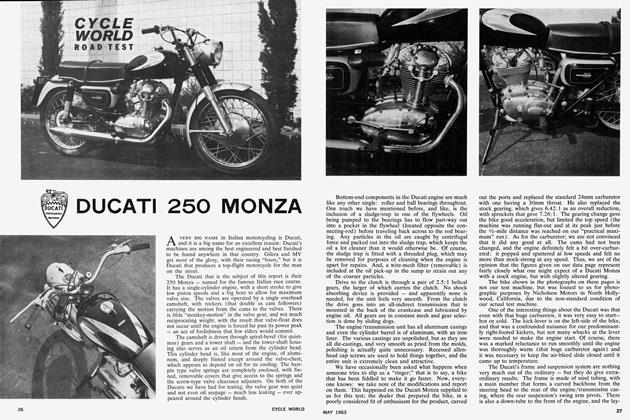

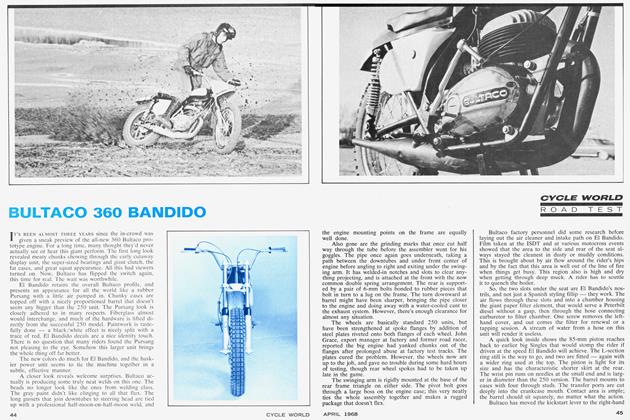

JAWA NEVER DOES anything rash. When Chief Engineer Jan Krivka wanted a bigger, more powerful motorcycle for the 1969 International Six Days Trial, he didn't wait long to begin development. He and Josef Josif, chief of Jawa construction, got busy immediately. Soon, they had a prototype frame, while others were still busy with The Powerplant. That prototype first saw light in 1964, and was ridden by Vlastimil Valek. "The banana frame Jawa," they called it. Now the machine is finished. We've waited five years for it. Seldom does one get so close to such an impressive motorcycle.

All testers agreed that the Jawa's suspension is almost ideal for California desert riding. The front end geometry allows

extremely good directional control and desired slowish steering. The front fork uses high-stepping 32-in. -long stanchions with 7-in. travel. On fast, rough surfaces, however, the rear end tends to bounce a bit. The cast aluminum chain case is partly responsible for this situation as it contributes a sizable 9 lb. to the unsprung weight. But the question of removing this cover should be carefully weighed. It is a valuable adjunct on a machine of this sort because its presence can easily treble chain life, and broken chains are not particularly rare in enduro racing.

The swinging arm is made of flat-sided oval section chrome moly tubing, and, in keeping with motocross-enduro design, is rather long in relation to wheelbase. The swinging arm measures 18 in. from axle center to the arm’s pivot point, while the wheelbase is 54.5 in. The frame must be one of the strongest units ever produced by the industry. Most noticeable, of course, are those crescent-shaped side members (hence, “banana frame”). These sections measure almost 2 in. wide and 0.9 in. thick. At the lowest point of the side members’ arcs, tabs are attached which serve as mounting points for the footpegs, engine/transmission unit and swinging arm, which pivots in bronze bushings. There also are two toptubes of smaller diameter that run slightly downward and straight back across the end of the arc.

The transmission performed flawlessly throughout the test. The dry clutch, which suffered some drag during a heavy hillclimbing session, is mainshaft-mounted with four porcelain-coated driving plates and three steel driven plates. Lever action is smooth and precise. The five-speed transmission is one of the best we have ever tested.

While Jawa and CZ share many components, there is little similarity in their engines and transmissions. The Jawa transmission does not shift gears by the sliding plate arrangement of its CZ cousins. Rather a pawl-driven rotating drum and three shifting forks change the ratios. The unit engine and transmission has been so designed that all the powerplanf s internals may be removed while the cases stay in the frame; this includes gears, shafts, shifting mechanism and crankshaft assembly. With the exception of high gear which is supported by a bronze bushing, all the gears rotate in 3by 8-mm needle bearings.

The crankshaft turns in needle main bearings. Needle bearings are also used on both ends of the connecting rod.

Front and rear fenders, fuel tank and number plates are made of thick fiberglass, presumably to reduce high-up weight. The finish on these units is handsomely rough and cobby. After all, soldiers don’t wear silk. The easily removable fuel tank is held down by an aluminum strap, which is hinged at the tank’s front, and a wing nut at the rear of the tank.

Seating seems uncomfortable for enduro riding—a tad too hard and narrow, as most American riders prefer less Spartan accommodations. On the other hand, the seat/footpeg relationship is very comfortable. Long rides do not leave you with cramped legs. (Continued on page 56)

The Jawa’s kickstarter is interesting because it swings forward. The beefy, cast aluminum lever can be kicked through with relative ease while sitting aboard the big Jawa. A 402-cc two-stroke with a 10.5:1 compression ratio requires a lot of leverage to get it going. But the ISDT Jawa is one of the easiest starting “monster poppers” around.

At first though, it was a different story. When we took delivery of the bike it was brand new and tighter than a weightlifter’s wristwatch. After CW staffers took turns wheezing and puffing over the kickstarter, the machine, with a senior staffer perched regally in the saddle, was pushed down the street by lower ranking members of the organization. After several passes, the engine snapped into life, and the bike and senior staffer went burbling and crackling down the street. Since then, the Jawa has never shown a reluctance to fire. One or two kicks will do it for cold starts, along with a speck of tickling and compression releasing.

Jawa’s ignition is a dual coil-single breaker points system with a spark plug situated on each side of the “dekompresor.” On the machine’s left side, below the seat and shielded by its upholstery, are two toggle switches. Each one controls a separate coil. They can operate simultaneously or, when one fails, individually. The flywheel magneto provides three circuits for current, two 1 2-V circuits for lighting and a 6-V winding for ignition. All the wiring has been waterproofed externally, while the points and magneto are safely ensconced behind a watertight magnesium casting on the engine’s left side. Incidentally, the Jawa manual indicates that ignition advance is adjusted by a slabeho papirku (cigarette paper) placed between the points. This method should prove popular with hippies and other roll-your-own types.

Riders not familiar with enduro equipment may find the chronométrie Smiths speedometer takes some getting used to, not only because it reads in kilometers per hour, but also because it is entirely gear-operated with no magnets in the dial head, and the needle moves in 5-kmph jerks, rather than smoothly sweeping the dial. While this is typical of such chronométrie instruments, they are more accurate and consistent under adverse weather conditions. The unit also has a trip reset knob, a necessity for enduros.

That U-shaped bar mounted under the crankcase seems inadequate for serious enduro riding. Nothing less than a complete bash plate is needed to protect the machine’s vitals from hostile elements. And, as mounting provisions already exist, the mod should take minimal effort.

The 400-cc Jawa has a very strong exhaust note. And even though there’s a baffle in the exhaust, the bike can be heard for some distance away. The three-piece pipe is tighter at the joints than most other makes, but still oozes some gas/oil soot from the forward juncture of the expansion chamber. However you can t be too critical of this because 1) it’s a competition bike and, 2) multi-piece exhaust pipes almost always leak anyway.

The Jawa manual strongly cautions against tampering with the exhaust system’s design, except for cleaning the silencer core. Any such alterations will assuredly inhibit engine output. The unit is designed along contemporary expansion chamber lines, but with many crucial adaptations for the highly individualistic Jawa engine. As the exhaust pulse reaches the expanded section of the pipe it slows down, at which time a negative shock wave is reflected back up the pipe. The function of this first wave is to shove any fresh intake mixture that’s crept past the port back into the cylinder. By this time, the gas in the expansion chamber is making its way out of the pipe by way of the silencer core. The resultant throttling effect causes a second pressure wave to shoot back up the pipe. The secondary pulse actually seals the port until it is closed by the piston. While this is only general expansion chamber theory and not exclusive to the Jawa’s exhaust system, it illustrates how critical a two-stroke exhaust syste/n is; it literally controls intake and exhaust timing. This also explains the phenomenal flexibility of the Jawa engine; indeed the power curve is almost as flat as the proverbial pancake.

In all, the Jawa’s performance is excellent. It handles remarkably well for a 295-lb. machine. With its five gears and Herculean torque range the bike is capable of climbing the highest slopes with ease and still attain speeds of 85-90 mph. The ratio spacing is just right, while the engine never seems to work hard. Testing sessions at Saddleback Park revealed the bike’s tractor-like determination. In fact, so obvious is this trait that “The Tractor” became its nickname. Even many four-strokes we have tested cannot equal the Jawa’s chugability. And throughout the entire test, we could not find an off-road riding condition that could absorb more than the Jawa could produce. As an enduro machine, it is the thoroughbred that the factory has been working on for the past five years. It is designed expressly for the International Six Days Trial, a grueling, brutal race of 200-plus miles-per-day over some of the most uncompromising terrain in Europe. No doubt, it will acquit itself honorably. [O]

JAWA

402-CC GELANDESPORT