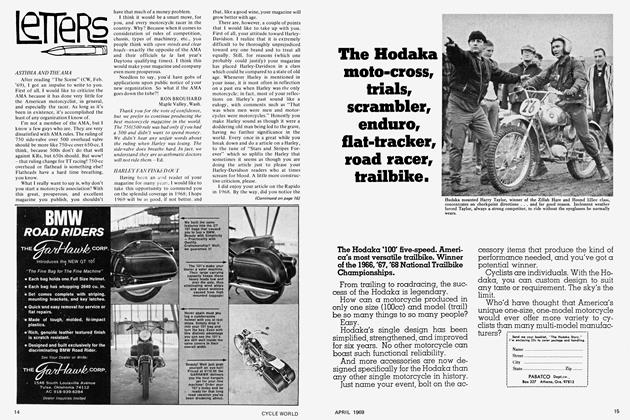

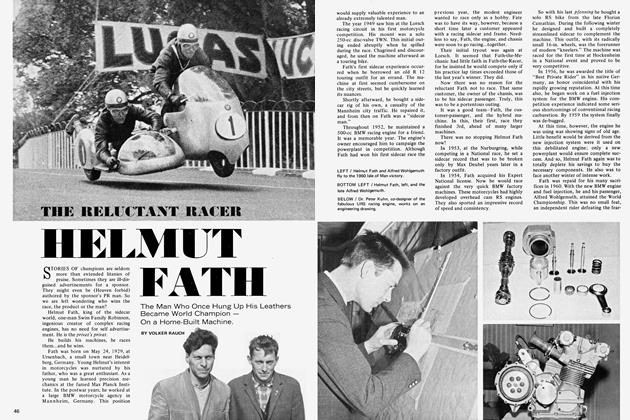

THE GREATEST RACE OF THEM ALL

RICHARD C. RENSTROM

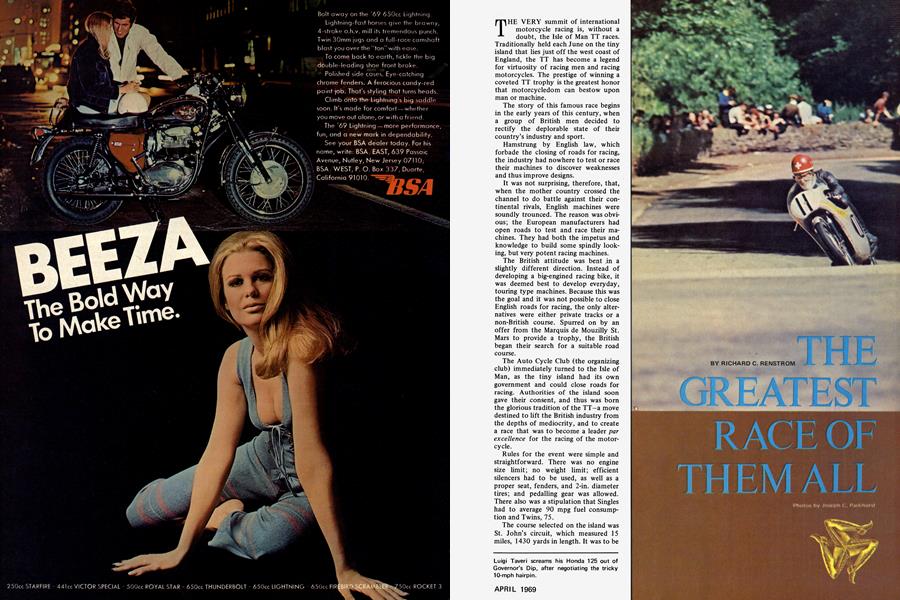

THE VERY summit of international motorcycle racing is, without a doubt, the Isle of Man TT races. Traditionally held each June on the tiny island that lies just off the west coast of England, the TT has become a legend for virtuosity of racing men and racing motorcycles. The prestige of winning a coveted TT trophy is the greatest honor that motorcycledom can bestow upon man or machine.

The story of this famous race begins in the early years of this century, when a group of British men decided to rectify the deplorable state of their country’s industry and sport.

Hamstrung by English law, which forbade the closing of roads for racing, the industry had nowhere to test or race their machines to discover weaknesses and thus improve designs.

It was not surprising, therefore, that, when the mother country crossed the channel to do battle against their continental rivals, English machines were soundly trounced. The reason was obvious; the European manufacturers had open roads to test and race their machines. They had both the impetus and knowledge to build some spindly looking, but very potent racing machines.

The British attitude was bent in a slightly different direction. Instead of developing a big-engined racing bike, it was deemed best to develop everyday, touring type machines. Because this was the goal and it was not possible to close English roads for racing, the only alternatives were either private tracks or a non-British course. Spurred on by an offer from the Marquis de Mouzilly St. Mars to provide a trophy, the British began their search for a suitable road course.

The Auto Cycle Club (the organizing club) immediately turned to the Isle of Man, as the tiny island had its own government and could close roads for racing. Authorities of the island soon gave their consent, and thus was born the glorious tradition of the TT—a move destined to lift the British industry from the depths of mediocrity, and to create a race that was to become a leader par excellence for the racing of the motorcycle.

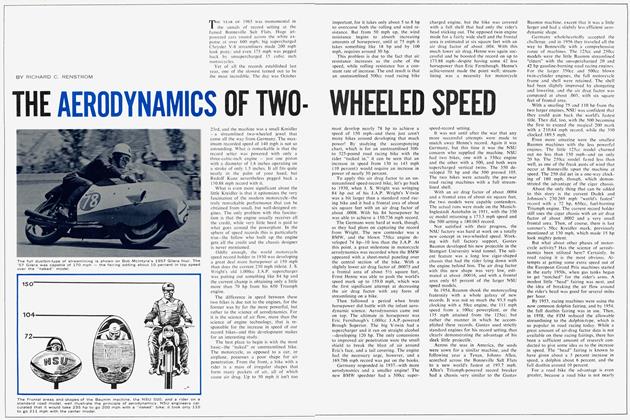

Rules for the event were simple and straightforward. There was no engine size limit; no weight limit; efficient silencers had to be used, as well as a proper seat, fenders, and 2-in. diameter tires; and pedalling gear was allowed. There also was a stipulation that Singles had to average 90 mpg fuel consumption and Twins, 75.

The course selected on the island was St. John’s circuit, which measured 15 miles, 1430 yards in length. It was to be covered 10 times during the race. There was a half-time break of 10 min. for mechanics to repair the bikes and for the riders to rest. The road was cobblestone and rutted dirt—a far cry from the smooth tarmac of today.

The Vintage Era - 1907 to 1930 - The Days of Dirt, Belt Drive and Pushing Uphill

The first epic found 25 starters—18 in the single-cylinder and 7 in the twin-cylinder class. Frank Hulbert and Jack Marshall were the first away on their Triumph Singles, followed by the famous Matchless racing brothers, H.A. and Charlie Collier. Despite the other 21 competitors, the race was among these four men. Charlie Collier led from start to finish. His single-cylinder bike averaged a speedy 38.23 mph over the rough roads. His gas mileage was 94.5 mpg, but this was exceeded by Marshall’s Triumph, which returned with a figure of 114 mpg—some 11 min. behind Collier. Rem Fowler brought his Norton home first in the twin-cylinder class at 36.22 mph, and, as both the Matchless and Norton had pedals for starting and for use on hills, the race was a victory for both man and engine power.

The following year it was decided to bar pedalling gear from the TT, but fuel consumption requirements were tighter; 100 mpg for for Singles and 80 mpg for Twins. Thirty-six men started that year—21 Twins and 15 Singles. The TT became international when two Belgian-made FN four-cylinder models were entered. Jack Marshall reversed the previous year’s results by heading Collier into 1st place, with a speed of 40.4 mph, and fuel consumption of 117.6 mpg. Again, the twin-cylinder class was slower than the thumpers, with Harry Reed and his Dot averaging 38.59 mph.

Easily the fastest bike in those days, the Triumph Single also was known for its reliability. Possessing a side-valve engine with a bore and stroke of 85 by 88 mm, the 500-cc unit pumped out a lusty 3 bhp. Drive was by a single-speed belt arrangement, and the gear ratio was 4.5:1. Brakes were the friction-pad type on the wheel rims, resembling those currently used on foreign bicycles. Marshall’s Triumph weighed only 150 lb., but he still had to get off and help push up the steeper hills.

For 1909, the ACU again modified rules for the TT. The fuel consumption test was dropped. In its place a restriction on engine capacity was adopted. Because of the inferior performance of the Twins, it was decided to allow the multis 750-cc engines and limit Singles to 500 cc. There also was just one class that year-and the fastest man took home the TT trophy.

With the absence of a fuel limit and such a great advantage in displacement, it is no wonder that speeds greatly increased. The winner was Harry Collier, at 49.0 mph on a Matchless Twin. Lee Evans was 2nd on an American-made Indian Twin. Collier’s fastest lap was 52.27 mph—the first time the course had been lapped at the half-century figure.

The 1909 Matchless Twins were very fast. They featured a 1000-cc V-twin JAP engine that had its 85by 85-mm engine destroked to 85 by 65 mm to qualify for the 750-cc class. Single-speed belt drives were used; their questionable reliability was slowly improving.

For 1910, it was decided the Twins had too great an advantage in engine size, so the limit was reduced to 670 cc. Entries increased to 80, easily a record for an international race. Once again the name Collier was in the news, with Charlie taking the win at 50.63 mph on his Matchless Twin. Brother Harry came home 2nd, a batch of trusty Triumph Singles following the two bigger Twins.

For 1911, the ACU made some sweeping rule changes. First and foremost was the adoption of the 37.5-mile long “mountain” course. Circling the island, the new course featured nearly every type of road condition possiblefast and slow corners, jumps, towns, flat-out stretches, and the dreaded machine-killing climb up the mountain. From Ramsey Town to the Bungalow in the highlands was a climb of 1340 ft. in seven miles, and then a speedy drop down to Creg-ny-Baa.

This was a truly magnificent road racing course. It was a challenge for the British to conquer. Their machines had experienced problems on the steeper sections of the St. John’s course, and now they were to tackle the mountain road. British doubts also were increased by the first serious foreign invasion—the American Indians, with champion Jake de Rosier.

The TT was held in June, rather than September, that year, and a new Junior class, with Twins limited to 340 and Singles to 300 cc, was added. The formula for the Senior TT also was changed to 585 cc for Twins and 500 cc for Singles. In addition, the muffler requirement was dropped, thus allowing the engines to develop more power. There were 104 entries received for the two events; the TT truly had become the pinnacle of motorcycle racing.

The Junior race was well represented by the British Humber, New Hudson, Douglas, AJS, Matchless, and Zenith. Foreign flavor was provided by the German NSU, Swiss Moto Reve, and French Alcyon Singles. P.J. Evans won on his Humber Twin at 41.46 mph.

The Senior TT had drama of its own. Over three-quarters of the British bikes had single-speed belt drives, and the riders were limited to even smaller engines to make the climb up the mountain. Then there were the flashy red Indians with their two-speed countershaft gearboxes and all chain drive. The reputation of these speedy Indians had spread all around the world.

Jake de Rosier led from the start, followed closely by Charlie Collier on his Matchless and O.C. Godfrey on another Indian. Indians also were 4th and 6th. Collier then took the lead, but soon was forced to spend 4 min. repairing a flat tire. He eventually finished 2nd, but was disqualified for taking on fuel while in the race. This made a 1-2-3 victory for Indian. Painfully the advantages of a good frame, a countershaft gearbox and all chain drive were set before the Europeans. Godfrey’s winning speed was 47.6 mph.

For 1912, it was wisely decided to equalize the engine size formulae to 350 cc for all Junior machines and 500 cc for all Senior class bikes. The Junior TT was copped by Harry Bashall on a Douglas—one of those weird looking, opposed Twins with the engine lying in-line with the frame. Th.e 344-cc engine featured side valves and a rather complicated arrangement of two primary chains and two gear control levers which provided four speeds from the two-speed gearbox.

In the Senior TT, the British showed the world they were quick to learn the lesson taught by Indian the previous year. Nearly everyone was trying some sort of gearbox and chain drive arrangement. Frank Applebee romped home the winner on his Scott, with a host of Triumph Singles and Matchless Twins behind him.

The Scott was an unusual bike, with its twin-cylinder two-stroke engine and water cooling. It had a two-speed gearbox and all-chain drive. The Scott packed the very high gear ratios of 4.8 and 3.0:1. Braking power still was provided by friction pads on the wheel rims.

In 1913, the Scott once again mastered the best of the four-strokes—this time with Tim Wood in the saddle. Hugh Mason was the victor in the Junior TT with a JAP-powered N.U.T. machine. The JAP engine was a V-twin with overhead valves—one of the first successes of the ohv engine type.

For 1914, it was decided to require Junior machines to cover five laps, and Senior bikes, six. Thus reliability, as well as speed, was emphasized. The Junior race saw the return of the Single to the winner’s circle, with Eric Williams leading the AJS team into 1st, 2nd, and 4th places. The 348-cc “Ajays” were fine little racers that had side-valve engines with a 74by 81-mm bore and stroke. A two-speed gearbox was used in conjunction with a dual primary chain setup to the clutch. The engine shaft had two sprockets of different sizes, one of which could be engaged to the shaft by a sliding dog. This gave the little thumper four ratios, as well as the Junior TT trophy.

The Senior TT witnessed a new name, as Cyril Pullin won at 49.49 mph on his Rudge Single. The Rudge featured a popular type of engine for those early days—the inlet-over-exhaust arrangement, which meant it had an overhead inlet valve and side exhaust valve. The gearbox was multi-ratio, which gave a nearly unlimited number of ratios through expansion of pulleys and belt drive.

Then came World War I, and racing was suspended until 1920. A slight change in the Island course that year increased it to 37.75 miles-its present length. As an experiment, a 250-cc trophy was added to encourage lightweight class participation. The inclusion of a 250-cc class within the Junior race was the cause of great mirth in many camps, but, when R.O. Clark brought his two-stroke Levis into 4th place in the Junior event, laughter ceased. The Top Hats began thinking seriously of a 250-cc class all to its own.

The Junior TT witnessed a great new engine that year—the new 350-cc AJS. The AJS was a 74by 81-mm Single with a hemispherical combustion chamber and ohv setup that allowed excellent engine breathing. The valves were set at 90 degrees to each other and were operated by pushrods. The gearbox was a three-speed countershaft affair with the double-primary chain-sprocket setup that gave six ratios. The rear wheel featured an internal expanding brake, which was a great milestone, but the front wheel still retained the frictionpad arrangement.

The AJS was a fantastically fast motorbike for its day, but its reliability didn’t match the speed. Only one machine finished, but that was in 1st place. Cyril Williams was the victor at 40.74 mph, after pushing the motorcycle the last few miles following a breakdown. Tommy de la Hay took the Senior TT at 51.79 mph on a very standard sidevalve Sunbeam Single, and Doug Prentice took the 250 Trophy on his New Imperial.

The following year, 1920, saw Europe greatly recovered from the war, and the TT experienced a great resurgence of interest and manufacturer support. The 250-cc class was taken by a New Imperial with a single-cylinder JAP engine, and the ohv thumper averaged a > surprising 44.61 mph.

The big news in 1921 again was the AJS, however, as the firm was working the bugs out of its ohv design. Largely redesigned, the AJS had a new, lower frame, a three-speed gearbox with ratios of 4.9, 6, and 9.3:1, and a new cylinder head. Tire size was 2.25-26, total weight was only 190 lb., and maximum speed, approximately 75 mph.

With a finishing order of 1, 2, 3, 4, and 6, the marque dominated the Junior TT. Eric Williams was the victor at 52.11 mph. Then, in the Senior TT, Howard Davies took his little 350 to victory at the record speed of 54.49 mph. Truly, it can be said that the AJS showed the world the advantage of the hemispherical combustion chamber design.

For 1922, the AJS was improved by fitting internal expanding brakes to both wheels, and Tom Sheard again won for the marque the Junior TT trophy. His speed was 54.75 mph. Geoff Davison took the newly created Lightweight TT on his two-stroke Levis, and Alec Bennett won the Senior on his Sunbeam side-valve Single at 58.31 mph.

The following year, a new event, a sidecar race, was won by Fred Dixon on a Douglas, and Tom Sheard kept the marque in the news with his Senior TT win at 55.55 mph. These Douglas racers were unorthodox, with their opposed Twin ohv engines mounted in-line with the frame. However, they did have a weight advantage of only 250 lb., plus a low center of gravity. In the Junior, Stanley Woods won the first of many TTs that year on an ohv Cotton, and Jock Porter took the 250 on his New Gerrard.

The year 1924 saw a milestone in the history of the motorcycle when Alec Bennett won the Senior TT on his ohv Norton. With this win at the record speed of 61.64 mph, Bennett can be said to have ended the era of the side-valve engine. Jock Porter took the 175-cc trophy, and the brothers Kenneth and Eddie Twemlow took the Junior and Lightweight TTs on their New Imperials.

Howard Davies was the man in the news in 1925 when he took his newly launched HRD into a smashing Senior victory at 66.13 mph. Davies’ bike used the legendary JAP ohv Single, and the 8-in. brakes set a new standard in stopping power. Wal Handley took the Ultra-lightweight and Junior TTs on his Rex-Acmes that year, and Eddie Twemlow won the 250 race on his New Imperial.

Nineteen hundred and twenty-six was a monumental year in the annals of motorcycling. That was the year an sohc engine won a TT. The rider was Alec Bennett, his mount, the Velocette. The Velo featured a bevel gear-driven single overhead cam, and the speedy 350 won the Junior TT at 66.7 mph. It also started a wholesale rush to having the cams “upstairs.” In 1927, Velocette scored another big first, when its TT bikes appeared with a positive-stop foot gearshift.

The Senior TT was taken by the ohv Norton again, this time with Stanley Woods in the saddle at 67.54 mph. Paddy Johnston won the Lightweight TT on his Cotton. That year also marked the end of the “vintage tank” era, as the 1925 HRD had a saddle type gas tank which shrouded the engine and one top frame tube. Previously, the side-valve engines had been shorter than the new ohv units, so the fuel tank had been mounted on top of the engine, usually between two frame tubes.

The following year saw the new ohc Norton, which featured a long-stroking (79 by 100 mm) bevel gear-driven single cam engine that was fast enough to garner the Senior TT for Alec Bennett at record speed. The 500 model was followed by a 71by 88-mm 350 the following year, but the Junior mount was destined to wait a few years for success. The Junior TT that year was taken by Fred Dixon on his HRD, and Wal Handley won the Lightweight TT on an ohv Rex-Acme.

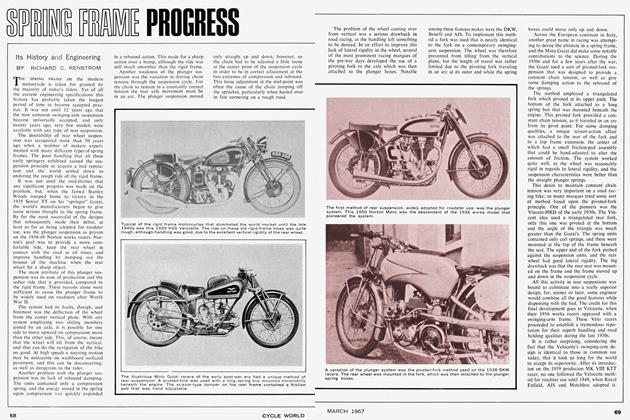

In 1928, some unusual machines came to the Island to try out innovations. One of the most interesting was the spring-frame Velocette. The frame had a triangulated rear section with the large coil springs mounted beneath the seat. Handling left something to be desired, so the bike was not used in the race. Instead, the factory relied on the standard ohc models which scored convincing 1st, 2nd, and 5th places.

The Senior TT was a reversal of the success of the ohc engine in the Junior event, as Charlie Dodson took an ohv Sunbeam Single to victory over the Norton cammers. The Sunbeam racing engines featured a new hairpin type of valve spring. As engine speeds increased, the problem of valve spring breakage had become severe, and the new hairpin spring soon was in wide use. The ohv engine was also victorious in the Lightweight TT, with Frank Longman the winner on a JAP-powered OK.

The overhead camshaft engine continued to fight it out with the ohv during 1929, with the cammer dominating the Junior TT and the pushrod engines wining the 250 and 500-cc events. The Velocette, in particular, was a truly magnificent racing machine for its day. It took 1st, 3rd, 5th, and 6th in ihe Junior TT with an ohc AJS in 2nd position. The little 350 featured a rigid frame with a girder front fork, and the cast iron engine operated on a 7.5:1 compression ratio. Breathing through a 1.062-in. carburetor, the 350 pumped out about 85 mph through its 5.25:1 gear ratio. A three-speed close-ratio gearbox was used, and the bike weighed 265 lb.

The ohv engine still held sway in the Senior TT, where the greater reliability of the tried and proven pushrod design often made the difference. Charlie Dodson once again was the winner on his Sunbeam, and at the record speed of 72.05 mph. The 250-cc event was won by Syd Crabtree on a JAP-powered

The following year was the final year in the vintage era, and it ended with a high note for the ohv engine. The ohc Norton had been redesigned, but there were just too many bugs to be worked out of the engine before it would be raceworthy. The Velocette was also in the process of great technical advances which made it temporarily non-competitive. As a result, the only overhead cam success was Jimmy Guthrie’s Lightweight win on his AJS.

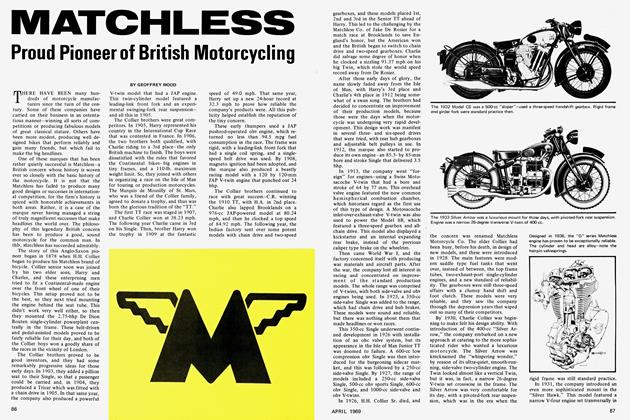

So the year of 1930 was a great one for the overhead valve engine, but history was to record that it also was to be the last time a pushrod engine was to win a Junior or Senior TT. The victorious machine was the Rudge—a now defunct company whose 1930 road racing models are considered great classics in the annals of the sport.

The single-cylinder Rudge was a very advanced machine for its day. It represented all the knowledge that had been gained from nearly 20 years of racing the pushrod engine design. Without a doubt, the most unusual feature was a four-valve engine. The 350-cc engine featured a hemispherical combustion chamber with the four valves set radially in the head. Two pushrods operated two rocker arms, which in turn operated the four rocker arms that opened the valves. Two exhaust pipes were used, and the engines were known for their reliability. The 500-cc engine also had four.valves, but they were set parallel in the head instead of having the radial setup.

The excellence of the Rudge did not end with the engine. It featured such advanced ideas as a four-speed footshift gearbox with all the shafts running on needle roller-bearings and massive 8-in. diameter brakes. The frame was an orthodox rigid unit with a girder fork on the front. The top speed of the 500-cc model was in excess of 100 mph, which was a substantial rate in those early days.

In the race, the Rudges scored a convincing 1st, 2nd, and 5th in the Senior TT, with Wal Handley winning at 74.24 mph. Tyrell Smith won the Junior event at 71.08 mph, and other Rudge riders filled 2nd and 3rd positions.

And so ended the vintage era—an epic of motorsport that saw the Isle of Man TT become the world’s greatest motorcycle race. From its feeble beginning in 1907, the race gained in stature until its 37.75 miles of road were considered to be the supreme test of man and machine. The race grew from a minor affair that interested only a few of the more sporting manufacturers, to a spectacle par excellence for the connoisseur of fine motorbikes.

More important, though, was the contribution the Island course gave to motorcycle engineering and development. With its uphill and downhill stretches, short but fast straights, jumps, and corners, the circuit put a premium on stamina, handling, brakes, and gearboxes. The British industry participated with great gusto in the TT, and knowledge gained in the races helped bring these manufacturers to the very summit of engineering excellence.

During this vintage era, for example, the world witnessed the rise of the British motorcycle, from the American Indian victory of 1911, to a time when British motorbikes were considered the finest in the world. From crude and unreliable belt-driven machines of the pre-World War I days, the motorcycle developed into a speedy and reliable mount. Innovations included ohv engines, stable frames and robust girder front forks, foot gearshifts, the positive-stop gearshifts, two-, threeand four-speed gearboxes, and then the overhead camshaft engine. Other developments were the saddle type gas tank, effective internal expanding brakes, and dry sump lubrication systems. All these technical advances were proven on the famous Island—magnificent contributions to the development of the motorcycle.

So ends the Vintage Era—an era in which England ruled supreme. The following years brought a great foreign challenge and tremendous technical development of the racing motorcycle.

The Classic Era - 1931 to 1939 - The Days of Supercharged Singles, Twins, Threes and Fours

WHEN THE vintage years ended, in 1930, the Isle of Man TT race had been established as the summit of motorcycle racing excellence. From the early days when belt-driven motorbikes chugged around the circuit, the road racing motorcycle had evolved into a 100-mph machine that finally acquired a reputation of reliability.

During the late 1920s, the sport had suffered because of the economic depression. Reduced sales of new bikes allowed the world’s manufacturers very slim racing budgets. But the 1930s yielded recovery for the economy and the sport.

With increased sales came increased profits, which manufacturers poured into their development and racing programs. Even the governments of Italy and Germany became involved, as they invested huge sums of money to gain international prestige in their drive toward power in the pre-World War II days.

These economic and political forces greatly stimulated motorcycling-and the TT. In the nine years prior to the war, the racing motorcycle experienced the most rapid development in its history. From rigid frames, girder front forks, and pushrod-operated ohv Singles capable of 100 mph in 1930, the racing motorcycle developed into overhead cam multi-cylindered mounts with telescopic forks, swinging-arm frames, water cooling, and superchargers. These technical advances led to the creation of a magnificent racer with a speed of nearly 1 50 mph.

This colorful chapter in the Isle of Man story began in 1931, when the Norton overhead camshaft Single came into its own. Tim Hunt won the Senior and Junior TTs at 77.9 and 73.94 mph. These old 500and 350-cc thumpers were long strokers, with bore and stroke measurements of 79 by 100 mm and 71 by 88 mm, respectively. The single cam was driven by bevel gears and a vertical shaft. A cast iron engine and a fourspeed foot shift gearbox were used. Suspension was provided only by the girder fork on the front, as the frame was still the rigid type. The ride naturally was on the rough side, but the Nortons were very reliable at speed.

The Lightweight TT saw Graham Walker speed to a 68.98-mph victory on his 250-cc Rudge. This little Single featured the famous four-valve head design. All the TT winners that year were the trusty Singles—a type that was to undergo extensive development to remain competitive against foreign challenges.

The following year, Norton again dominated the races. The policy was a methodical step-by-step technical improvement each year. The 1932 Singles were modified with bronze heads, a set of small return springs on the front fork to help dampen the compression action, and large fuel tanks that gave the Nortons their famous cobby appearance. Stanley Woods took the Senior and Junior races at record speeds, and Leo Davenport won the Lightweight TT on his New Imperial Single.

For 1933, the Nortons were improved with a new aluminum alloy head and cylinder. The head had the alloy fins cast onto a bronze “skull,” and deep fins were moulded on the cast iron cylinder sleeve for improved heat dissipation. The Nortons once again swept the board in the Senior and Junior TTs. Woods became the first man to win at over the 80 mark when he averaged 81.04 mph on his 500-cc mount. He was followed by Nortons in 2nd and 3rd positions in both events.

The Lightweight TT was won by a most unusual machine—the Excelsior “Mechanical Marvel.” This British marque used a single-cylinder engine with two cams—one at the front, the other at the rear. These cams operated two pushrods which operated four rockers and valves. Two carburetors and exhaust pipes were used, and the four valves were in a radial position on the head. The Excelsior came straight from the drawing board to the TT, but that victory proved to be its only success. It later was dropped.

In 1934, the Nortons became the very essence of racing motorcycles. The problem of valve spring breakage had become serious, as the designers were using larger valves and higher rpm to obtain the ultimate in performance. To solve the problem, Norton adopted the hairpin type of valve spring. The head was modified for t^vo spark plugs. The bikes also acquired the “bolt-through” type of gas tank" and a megaphone exhaust that year. These Nortons were truly beautiful racing machines.

Maximum speed on the 500-cc model was nearly 110 mph, and the 350 was capable of approximately 100. The frame was still rigid and the front fork was the common girder type. Reliability and good handling were the hallmarks of Norton in those days, but competition was on its way.

In the early 1930s, the British Velocette had become quite successful in the Junior Class. In 1934, the marque decided to field a 500-cc stablemate for the smaller 350-cc Single. The larger Velo measured 81 by 96 mm, compared to the 74 by 81 mm of the 350. Both models had the bevel gear and vertical shaft drive to the single overhead camshaft, alloy heads and cylinders, a cradle frame, and massive magnesium alloy conical hubs with powerful 1.5by 7-in. brakes. These new Velocettes were known for fine handling and stamina. The Norton obviously had a challenger.

Another interesting attempt to dethrone Norton was the Husqvarna Twins ridden by Stanley Woods and Ernie Nott. These Swedish speedsters were V-twins, in both 350 and 500-cc sizes, and their performance was very good. The 500-cc engine had a bore and stroke of 65 by 75 mm and a compression ratio of 10:1. Two 1-in. Amal TT carburetors were used and peak power was 44 bhp at 6800 rpm. Pushrods operated the overhead valves.

The V-twin used a four-speed gearbox mounted in a rigid frame, and the Swedish-made girder front fork was replaced in the Island by a Webb TT type as the handling had not been satisfactory. As was common on most road racers in those days, a large 5.7-gal. fuel tank was fitted to satisfy the engine’s thirst for the petrol-benzol fuel. The Junior model was virtually the same, except for the smaller engine size.

The little Rudge won the 250-cc TT; then the company slowly passed out of existence. The Junior TT saw Norton once again the victor with Jimmy Guthrie leading teammate Jimmy Simpson home. Nott brought the Husqvarna into 3rd, followed by a gang of Velocette riders.

The Senior TT witnessed the beginning of the truly classical battles as Stanley Woods gave the Norton team a real scare. Woods ran 2nd early in the race, then began closing the gap. He clocked the fastest lap of the race on his third circuit. But the Husqvarna finally let him down, and Stanley retired within a few miles of the finish. Nortons scored a 1-2 victory with Guthrie and Simpson, and Walter Rusk brought the new Velo home in 3rd position.

In the spring of 1935, it was obvious that the winds were changing. Since 1930, the Norton had experienced very little competition, as the Rudge concern was slowly going broke and Velocette had been preoccupied with building a new factory and expanding its production. With the depression nearly over and sales booming all over Europe, many marques with new ideas were sniffing excitedly about the racing game. Change was in the air—exotic, fantastic, and urgent. Norton would have to fight to stay alive.

When the 1935 TT rolled around, the Norton camp was there, but their bikes were little changed from the previous year. Several more top-flight riders had been added to the team, but complacency overshadowed bike preparation. The gearboxes that year were the closeratio type, with ratios of 4.44, 4.88, 5.91, and 7.86:1 on the Senior model; and correspondingly lower with a 5.17:1 top gear on the 350 model. The two engines were identical to the previous year and packed only modest 7.25 and 7.6:1 compression ratios.

The Velocettes also were much the same as the previous year, but a MK V production 350-cc KTT model, newly introduced, established an excellent reputation. Other British manufacturers were busy. Royal Enfield entered a works 500 Single that featured a pushrod engine with a plain bushing for the big end bearing. The Enfield used, a four-speed Albion gearbox, rigid frame, and girder front fork. The speed was something like 110 mph, which was a very respectable rate for those days.

Another successful machine was the Excelsior Manxman-a Single available in 250-, 350and 500-cc sizes. The Manxman featured an sohc engine, though the rest of the bike was quite orthodox for its day. The 250-cc model was noted for its speed and reliability.

However, the most significent machine entered in the 1935 TT was none of these, as the challenge had become foreign. It is not that foreign bikes had not been entered before, because nearly every year several factories were represented. But 1935 presented a really serious foreign challenge for the first time since 1911.

The new antagonist was the Italian Moto Guzzi, with the great Stanley Woods as rider. Stanley’s mounts were unique and exotic-a 250-cc Single with its engine lying horizontally in the frame, and a 500-cc V-twin that was rumored to have its cranks at 180 degrees. The little 250 featured an sohc head, girder front fork, and a four-speed gearbox. The Twin had its cylinders at 120 degrees, and produced 44 bhp at 7500 rpm for a maximum speed of 112 mph. Other than the immense brakes, the most notable feature of the Guzzis was the rear suspension, which was provided by a triangulated rear frame section that was pivoted at the top and attached to a long spring box at its lower point.

A TT race had never been won by a bike with rear suspension, and a foreign machine had not scored a victory since 1911. Undaunted, Stanley won the Lightweight TT on his 250 Single and broke the lap record at 74.19 mph. This was the first time a foreign bike had ever won the Lightweight TT—the challenge was genuine.

In the Junior TT, Jimmy Guthrie, Walter Rusk, and Crasher White easily subdued the Velocette challenge, but the Senior TT was a different story. Guthrie led from the start, and had built up a 52-sec. lead by the end of Lap 3. Then came the drama, as Stanley began urging his Twin forward. At the end of Lap 4, he was only 42 sec. behind, then 29 on the fifth, and 26 at the end of Lap 6.

Casting the rev limit to the winds, Stanley screamed into the last lap after Guthrie. Second by second he pegged back the difference until he shattered the lap record by nearly 4 mph. He won the Senior TT by 4 tiny sec. Behind Stanley lay an 86.53-mph lap record, an 84.68-mph race record, the first winning rides on a spring frame motorcycle, and a badly trampled Norton reputation. For Norton, it was fight or go under.

Norton chose to fight. So did several other British manufacturers. By June the new Nortons were ready-and what beautiful machines they were. The most notable improvement was the adoption of a plunger type of rear suspension to improve road holding. The cylinder bore was increased fractionally to raise the capacity from 490 to 499 cc, and a remote mounted float bowl was fitted to prevent fuel frothing.

At Hall Green, the Velocette racing engineers also were very busy. The marque’s new racers featured a brilliant method of rear suspension—the modern swinging arm system. The 350 Velos had a new dohc head, but the 500-cc model retained the single cam setup. Possibly the most important item was the hiring of Stanley Woods, as the team needed a really great rider if it was to ever get to the top. The factory previously had bikes fast enough to win, but they never had had a capable rider.

Another outstanding British bike that year was the New Imperial Single, a 250-cc pushrod model that had an amazing turn of speed. The alloy engine had the oil tank contained in the crankcase in an effort to keep the center of gravity as low as possible. The frame was still rigid.

New Imperial also had a speedy 500-cc V-twin in 1936 that was virtually a double-up of the 250 engine. The cylinders were set at 60 degrees, and the bore and stroke were 62.5 by 80 mm. The powerplant turned to 8000 rpm, but the handling and roadability were not up to the speed. The alloy engine was housed in a rigid frame, and a four-speed Sturmey-Archer gearbox was used.

The foreign challenge was there in 1936, but not nearly so formidable as the previous year. The only truly raceworthy machine was the DKW—an unorthodox and colorful entry from Germany. The DKW was a two-stroke 250 which had the split-single piston arrangement. This unusual feature has two pistons on one articulated connecting rod, but with a common combustion chamber.

The romance of the design didn’t end there, however, as a third piston was mounted in a horizontal position. This piston acted as a compressor for blowing the fuel charge into the crankcase, and a rotary valve was used to time the crankcase charging. The two vertical cylinders had the intake ports in one cylinder and the exhaust ports in the other. Then, to top off this remarkable machine, water cooling was used. Horsepower was 25 at 4400 rpm.

This German challenge proved to be in earnest, too, as Stanley Woods took the DKW straight into the lead. The lead then see-sawed back and forth between Woods and Bob Foster, on his New Imperial, but the two-stroke finally blew while leading on the last lap. Foster romped home the winner.

In the Junior TT, Stanley streaked away on his dohc Velo. But the new engine proved to be too new, and Woods retired to let Ted Mellors do battle with the Nortons. Ted came home 3rd behind the Nortons of Fred Frith and Crasher White.

The Senior TT was a fantastically close battle as Guthrie witnessed Woods steadily reduce his early lead throughout the race until the final result left only 18 sec. between them. Stanley, however, did have the consolation of an 86.98-mph record lap.

(Continued on page 77)

ISLE OF MAN

Continued from page 70

An intensity of purpose was apparent in the spring of 1937. Motorcycle racing had become a leading sport in Europe, and international competition was mounting. Spurred on by government financial backing, the German and Italian marques began to develop some highly sophisticated designs.

Norton responded by introducing a dohc head on their works racers. The dual spark plug head was dropped in favor of a single plug, and the finning of the head and cylinder was greatly increased. The valve springs and valve stems remained exposed for cooling.

The Velocette works racers that year featured new sohc engines with all the valve gear enclosed, and the massive 9-in. square head set a new fashion for finning. Tappett adjustment was by eccentrically mounted rocker arms, and a metered jet method was used for lubrication. The inlet port was downswept and the float was remotely mounted on the oil tank. These were truly magnificent racing machines with the 350 churning out 32 bhp at 7200 rpm for a maximum speed of 117 mph, and with the 500-cc model producing 42 bhp at 6700 for 124 mph.

The foreign competition grew awesome. BMW sent over a fabulous supercharged Twin and DKW fielded a team on their blown 250s. The Singles were well represented with Guzzi 250 and 500 models, NSU 350 and 500 machines, and the Swedish 250 Husqvarna.

The Lightweight TT was strictly a foreign battle between the Guzzi and DKW, with Omobono Tenni taking the win on his Guzzi at the record speed of 74.72 mph. With this win came the end of British supremacy in the 250-cc class, for never again would they win the Lightweight TT.

In the Junior TT, the Norton team celebrated by taking the first three places with Guthrie, Frith, and White. Woods brought his Velo home 4th. The foreigners were soundly trounced. Guthrie’s fastest lap was 85.18 mph—a better than 3-mph improvement over the previous year.

The Senior TT once again provided a tremendous battle between the Norton and Velocette teams. BMW’s expected challenge failed to materialize, probably because it takes a few years to master the difficult 37.75-mile circuit. At the end of Lap 5, it was Woods in the lead, with Frith only 10 sec. behind. On Lap 6, they were tied for the lead, but on the last circuit Frith turned in a fantastic 90.27-mph lap to snatch the victory by 15 sec. This was the first time the course had been lapped at over the 90 mark, and the lone BMW rider in 6th position must have gained a new respect for British roadability.

During the long winter the search for more horsepower and improved roadability became frantic. In an effort to better control their supercharged horsepower, BMW engineers replaced the girder front fork with a hydraulically dampened telescopic fork. NSU continued to race their dohc Singles, but the racing department was hard at work on a new design.

In England, the Norton engineers responded by producing a totally new bike with many splendid technical improvements. The most notable was the new telescopic front fork that had compression and rebound springs but no hydraulic damping. Massive conical wheel hubs were cast from magnesium alloy, and the ribbed brake drums had air scoops for cooling.

(Continued on page 112)

Continued from page 77

In an effort to obtain greater rpm and more horsepower, the stroke was shortened from 100 to 94 mm on the 500, and from 88 to 77 mm on the 350. The bores were opened up from 79 to 82 mm, and from 71 to 76 mm on the two engines. The finning was again increased so that the head had a massive square appearance. The 500-cc model used a huge 1.312-in. carburetor. The Senior mount was said to produce 50 bhp at 6500 rpm for a top speed of 125 mph.

At Hall Green, Velocette modified some of the internal engine components to attain better reliability rather than speed. A new MK VII KTT model was produced for the private owner. This production racing Velo established a great reputation for its handling and stamina, and it, along with the AJS R7 350-cc racer, the Excelsior Singles, and the 350and 500-cc production racing Nortons, provided private owners with pukka racing machines.

Probably the most exciting British machine that year was the works AJS 500-a supercharged V-4. The new AJS certainly was not lacking in performance, but the roadability never matched the speed. The rather complicated powerplant also had many “teething” troubles.

Other British racing attempts included the Vincent 500-cc Single, and the Cotton, Excelsior, Rudge, and OK Supreme. Two surprising entries in the TT were a pair of American bikes—a 500-cc Indian and a 350-cc HarleyDavidson. Speed was notably lacking in both.

The 1938 TT series opened with the Lightweight event, and Ewald Kluge simply annihilated the opposition with his winning margin of 1 1 min., 9 sec. Kluge’s DKW twin-single averaged 78.48 mph, and his record lap was 80.35 mph. Lapping over the 80-mph mark was a first for a 250.

In the Junior TT, many predicted that Norton’s long string of successes would come to an end, as the Velocette had garnered the 1937 World Championship and appeared to be the faster. And so it was, with Stanley Woods and Ted Mellors leading home the Nortons of Frith, White, and Harold Daniell. Stanley set a lap record of 85.30 mph, a record that stood for 12 long years.

The Senior TT once again saw a classical battle, with Woods leading at the end of Lap 5. Harold Daniell then began to spur his big Norton Single harder and harder. On Lap 6, he turned a record lap and gained 5 sec. over Woods. Then, on his final circuit, Harold turned in his fabulous 91.0-mph lap that gave him a 15-sec. victory over

Stanley. Daniell’s lap record also stood for 12 years.

And what of the foreign challenge? The Fatherland had all sorts of problems. Georg Meier, the leading rider, had a spark plug stripped out just prior to the race, and Jock West came home in 5th position. So 1938 drew to a close with England soundly trounced in the 250-cc class, but firmly in charge of the Junior and Senior events.

During the winter, the quest for performance became intense. The Norton engineers, aiming for greater reliability, made only minor refinements to their TT bikes. Frith’s 350 engine was altered to measurements of 73.3 by 82.5 mm. The Velocettes were much the same as in 1938, but a new Mk VIII KTT model with swinging arm rear suspension was produced. The Mk VIIIs were splendid racing machines, and they accounted for 25 of the first 35 finishers in the Junior TT. The KTT produced 32 bhp at 7200 rpm on a 10.9:1 compression ratio—good enough for 112 mph.

For 1939, the traditional British racing Single took a back seat, as the many exciting supercharged models provided a feast for the technical aficionado. Britain herself even got into the act with Velocette trying out their new 500-cc Twin in practice and AJS racing a team of V-4s in the Senior TT. The AJS had acquired water cooling during the winter, and the engine was at last rehable, even if the handling was not the best.

The Germans were there in force, with 1938 World Champion Georg Meier more determined than ever. The blown BMW Twin had been clocked at 145 mph during the previous grand prix season, and Meier had learned the TT course. The DKW two-strokes were also improved, as an eccentric vane supercharger had replaced the piston compressor. Horsepower was listed as 40 on the 250, and 56 on the new 350-cc model. Maximum speeds were 111 and 122 mph, but the water cooling pushed the dry weights up to 316 and 350 lb. Handling was known to be a problem.

Other new superchargers were the NSU Twins, which produced 65 and 90 bhp, respectively, from the 350 and 500-cc engines. Both powerplants featured double overhead cams, eccentric vane superchargers, and air cooling. The NSU racers used girder front forks and plunger rear suspensions. Their speed was fantastic.

Not to be outdone by the superchargers, Benelli and Guzzi entered outstanding racing bikes with an emphasis on light weight, powerful brakes, and superb handling. The Benelli was a 250-cc Single that turned to 9000 rpm and ran 110 mph. The Guzzis were 250and 500-cc Singles with traditional horizontal engines and outside flywheels.

And so to the races. The Lightweight TT again was dominated by foreign contenders. The Guzzis set an early pace, only to drop out and let Ted Mellors through to win on his Benelli. Kluge, on a DKW, was 2nd. The Benelli victory was a fine example of the advantage a little rain can give to the lighter machine.

The Junior TT was a real donnybrook with the DKW, Norton, and Velocette teams all in the fray. Woods finally won, with a Norton 2nd, a DKW 3rd, and two more Velos in 4th and 5th positions. The race was marked by the great number of high speed finishers—a tribute to the British policy of producing racing machines for the private owner.

In the Senior TT, the era of British supremacy finally came to an end when Meier romped home the winner. Meier’s win at the record speed of 89.38 mph was an easy one, too, as he used the phenomenal performance of his 78-bhp Twin to scorch down every straight miles an hour faster than the British Singles.

So it was. Meier’s victory brought an end to the era, for never again would the Island echo to the scream of supercharged exhausts. The BMW and NSU Twins, the DKW, the AJS V-4, and the Velocette Twins no longer would be seen in full flight winging and howling over the Sulby Mile or on the descent to Creg-Ny-Baa.

It was the farewell prewar performance of the magnificent Singles that were raced with such gusto—the Nortons, KTT Velocettes, the Moto Guzzi Condor, the AJS R7, New Imperial, Excelsior, and Benelli. Then the intrigue of the V-twins—the Husqvarna, New Imperial, and the Guzzi. These were great classics—every one of them.

In this nine-year period, the winning speed had risen over 15 mph in the Senior TT. The colorful works racers had, by 1939, pioneered every major engineering feature that is in use today. For pure uninhibited engineering and the nostalgia of fascinating machines and hard-fought races, this era was the greatest hour the Island has ever known. After the war, it was decided to abolish supercharging for international racing, and the magnificence of this era became just pages of a history book. But it is a history that does not die. The leaderboard results of the 1939 Senior TT—the last TT to hear the drone of a supercharged engine:

1 Georg Meier . . BMW, supercharged Twin 2. Jock West ... BMW, supercharged Twin 3. Fred Frith ....... Norton, dohc Single 4. Stanley Woods . . Velo, works 500 Single 5. J.H. White ....... Norton, dohc Single 6. I—J. Archer .... Velo, works 500 Single 7. Ted Mellors .... Velo, works 500 Single 8. Ginger Wood ..... Norton, Inter Single 9. Maurice Cann .... Guzzi, Condor Single 10. J.C. Galway ...... Norton, Inter Single 11. Walter Rusk .... AJS, supercharged V-4 12. David Whitworth . Velo, KTT 350 Single

To follow-the Postwar Adjustment. [Qj