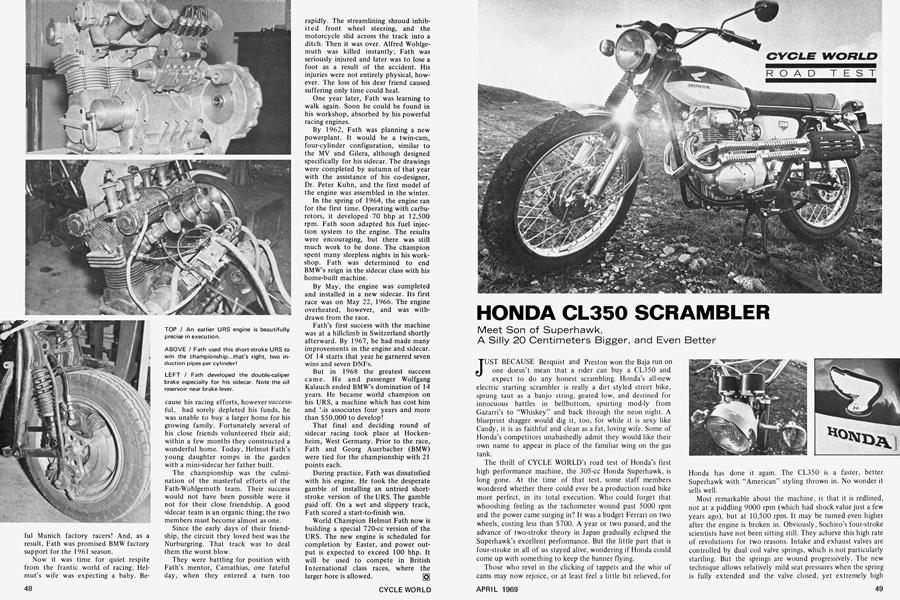

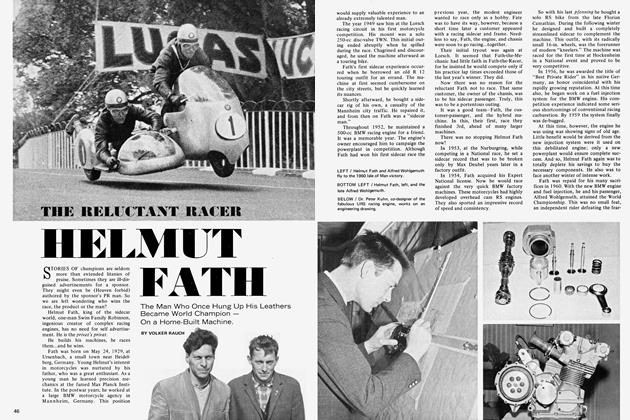

HONDA CL350 SCRAMBLER

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

Meet Son of Superhawk, A Silly 20 Centimeters Bigger, and Even Better

JUST BECAUSE Berquist and Preston won the Baja run on one doesn’t mean that a rider can buy a CL350 and expect to do any honest scrambling. Honda’s all-new electric starting scrambler is really a dirt styled street bike, sprung taut as a banjo string, geared low, and destined for innocuous battles in bellbottom, spurting mod-ly from Gazarri’s to “Whiskey” and back through the neon night. A blueprint shagger would dig it, too, for while it is sexy like Candy, it is as faithful and clean as a fat, loving wife. Some of Honda’s competitors unabashedly admit they would like their own name to appear in place of the familiar wing on the gas tank.

The thrill of CYCLE WORLD’S road test of Honda’s first high performance machine, the 305-cc Honda Superhawk, is long gone. At the time of that test, some staff members wondered whether there could ever be a production road bike more perfect, in its total execution. Who could forget that whooshing feeling as the tachometer wound past 5000 rpm and the power came surging in? It was a budget Ferrari on two wheels, costing less than $700. A year or two passed, and the advance of two-stroke theory in Japan gradually eclipsed the Superhawk’s excellent performance. But the little part that is four-stroke in all of us stayed alive, wondering if Honda could come up with something to keep the banner flying.

Those who revel in the clicking of tappets and the whir of cams may now rejoice, or at least feel a little bit relieved, for Honda has done it again. The CL350 is a faster, better Superhawk with “American” styling thrown in. No wonder it sells well.

Most remarkable about the machine, is that it is redlined, not at a piddling 9000 rpm (which had shock value just a few years ago), but at 10,500 rpm. It may be turned even higher after the engine is broken in. Obviously, Sochiro’s four-stroke scientists have not been sitting still. They achieve this high rate of revolutions for two reasons. Intake and exhaust valves are controlled by dual coil valve springs, which is not particularly startling. But the springs are wound progressively. The new technique allows relatively mild seat pressures when the spring is fully extended and the valve closed, yet extremely high spring tension as the valve opens and the spring stacks up on the tighter winding to give the required control at high rpm. The exhaust valve diameter is about 90 percent that of the intake valve—a larger than usual ratio, as 80 to 84 percent is considered by some flow theorists to be the optimum range. But the passage of fuel is carefully restricted as it passes from the carburetor through the intake port, increasing the efficiency of the intake. The fuel passage, beginning at the carburetor bore (1.255 in.), narrows at the manifold (1.195 in.), narrows again through the port (1.175 in.). As the port curves around the valve guide it becomes oval but larger in area, and is finally 1.260 in. in diameter at the valve seat. The “hourglass” concept is designed to accelerate the fuel charge on its way through the port and thereby aid cylinder filling at the high rpm involved.

What is interesting about all this, is that the machine is much more tractable than the somewhat cammy Superhawk, which showed a reluctance to torque itself away if the throttle was opened at engine speeds below 5500 rpm. The CL350 has a much broader torque band and will pull from about 3000 rpm in high gear without giving the rider that clammy feeling that he is being unkind to the engine. Part of the reason may be that Honda purposely restricts the 350’s exhaust header size to keep the gas velocity high when the engine is turning over at slower speeds. The exhaust pipes look pleasantly large in diameter, but there is actually a smaller pipe inside the larger one to narrow the passage. In addition, the CL350’s exhaust system—two upswept pipes terminating in one boxy muffler/spark arrester—lowers the power band, because it is shorter and more restrictive than the big, separate silencers used on its running mate, the CB350, a higher geared, faster machine for the road rider with purist tastes. The CB uses all of that 10,500 rpm to achieve its 36 bhp. The CL’s power peak is dropped to 9500 rpm, where it produces 33 bhp.

CB or CL, it is clear that Honda has concealed a wolf in sheep’s clothing for purposes of tractability, and that the real power potential of this sohc Twin is yet to be revealed by an enterprising tuner. Simply replacing the 350’s mild cams with a moderate racing grind produces remarkable results. The five-speed gearbox allows a much narrower power band, so tuners will find the 350 a “natural.”

The prospective buyer may ask whether the engine is built to stand the strain of all those “R’s.” The answer is yes. Construction from bottom to top is positively tank-like. The 350 has four main bearings—three roller bearings, and a ball bearing on the drive side. The crankcases hold the outer bearings in place, while a large cast aluminum bearing cap with four bolts holds the center main bearings to the upper crankcase. The crank assembly boasts four flywheels, two for each roller bearing crankpin. The crank assembly is Honda’s customary 180-degree layout, yet doesn’t produce the handnumbing resonance which used to be one of the Superhawk’s few faults. The 350 is a smooth, well-balanced engine, at any speed.

Robustness is carried into the upper end as well, with eight cylinder through-bolts, and heavy rocker boxes. The chaindriven single overhead cam is not supported in the middle, but this is hardly necessary, as it weighs a hefty 3 lb. The camshaft rides directly in aluminum end caps, rather than in ball bearings. Sturdy, plain-ended rocker arms ride on eccentric spindles, which are externally adjustable by the simple removal of the covers on each side of the head.

Power is taken from the engine in a rather novel way. The gears are straight cut, a feature which is most efficient, but is noisier than the alternate less efficient method of using helical gears. However, the drive gear on the 350 is actually two rows of gears, the teeth on one row staggered in between the relative position of the teeth on the second row. The power is picked up by two rows of teeth on the clutch shell disposed in corresponding alternation. The effective time the gears are in mesh is doubled—the same factor which makes helical gears silent—while avoiding the power robbing side loading of a helical gear.

The 350 clutch has eight metal and eight friction plates, running in oil bath, with a four-spring pressure plate. Its action was smooth and firm during the miles spent on the road, although it got mushy after 15 banzai mns down the quarter-mile, recalling its ancestor’s need for readjustment after the first few hundred miles of ownership. The in-unit transmission bears some similarity to the Superhawk’s—in the shifting drum, shaft and forks. The gear layout is different to accommodate the fifth gear, and the required extra shifting fork. Power goes in through the clutch at the right side and is delivered to the countershaft sprocket at the left side. Caged needle bearings carry the mainshaft and layshaft on the clutch side, with twin roller bearings serving on the sprocket side. Both upshifts and downshifts were smooth, and could be made faultlessly regardless of engine speed. The short-travel lever required minimum toe pressure.

The frame is nothing out of the ordinary—pressed steel backbone and tubular downtube, cradle and supporting members. It is inexpensive to build because pressed steel allows spot welding. It is strong because it is heavy. The exhaust system, because of the extra inner piping, weighs in at an anvil-like 23 lb. The engine itself, while looking massive, weighs only 125 lb., so it is clear where the other part of 363 lb. must be.

The ride is firm, a characteristic feature of Japanese road bikes, which is one good reason why the CL350 had best be restricted to pavement and relatively smooth graded roads. It flicks into turns in quite secure fashion. In a seeming paradox, it is a lightly handling machine but it steers somewhat ponderously. This is no fault of design; the heaviness comes from all the gadgetry hung on the front end: full sized headlight, speedometer, tachometer, buttons, switches and a pair of large turning signal pods. A ribbed front tire, instead of the CL’s universal, would be vastly superior for road work, and reduce the indecision about tracking and the angle of lean needed during a hard corner, but, after all, ribbed tires are just not the “in” thing on a street scrambler. The purist will get his ribbed cover on the front of the CB.

Straight-line performance of the CL is excellent, if not overwhelming. It will top 100 mph, and bustles through the quarter-mile timers at 81.37 mph, with a 15.38-sec.e.t. We can’t help wondering what it would do if its displacement were really 350 cc like its name, instead of only 325 cc. And, it would be straighter to John Q. Public to call a spade a spade.

Starting is easy. Turn the key, fiddle with the choke lever to the left of the dual constant velocity Keihin carburetors, press the starter button and fiddle with the choke lever some more while the engine warms a bit. But that drill should be nothing new to owners of the Superhawk, the bike that started it all.

And so we doff our hats, or should we say helmets, to the CL350. What a magnificent engineering feat it is to mass-produce a machine for the enthusiast that may be ridden with insouciance by people who know next to nothing about motorcycling. A most compelling testimonial. [o]

HONDA

CL350 SCRAMBLER