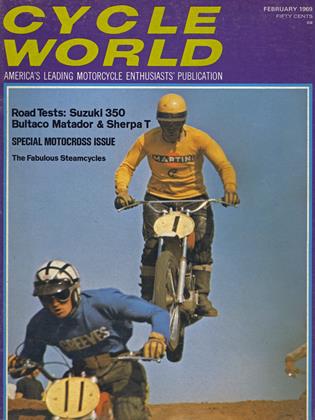

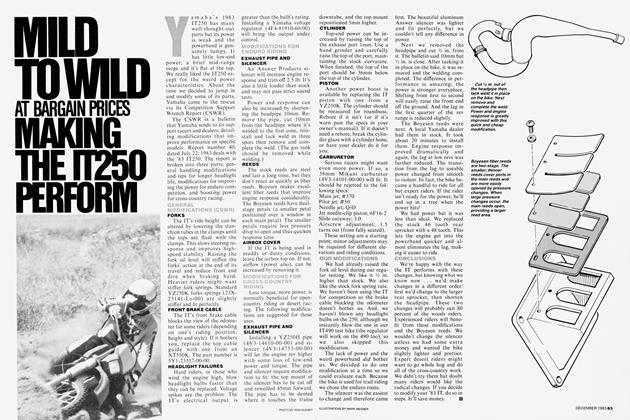

Honda de Baja

The Preparation Payoff, Or, How to Win the 1000

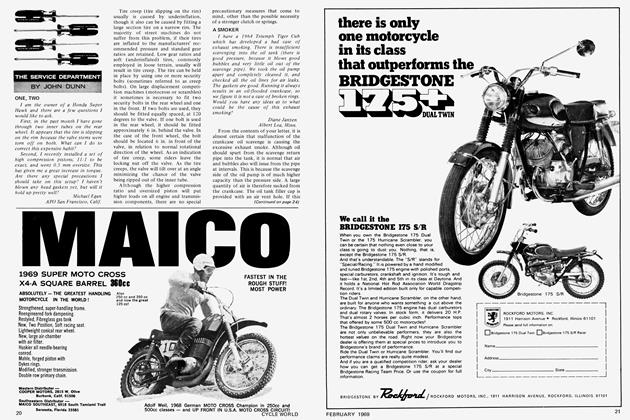

LARRY BERQUIST and Gary Preston wore brightly colored scarves during their winning ride in the Mexican 1000 race, yet carried no spare tubes as they plunged down Mexico's rocky, thorny Baja peninsula. Were they careless, or wildly optimistic, in ignoring the possibility of punctures? The uninitiated might think so, but the riders and their sponsor, Long Beach Honda, disagree. Extensive pre-Baja race experience indicated that the Honda's tires, after treatment with a few ounces of sealant compound, would withstand the 832-mile grind. Calculations were correct-the victorious 350 Honda completed the race in La Paz with its Dunlop Universal covers, and the tubes, in fine condition. And, the scarves were not worn for effect. They formed a communication system between the Long Beach company's two entries-the winning 350, and a 250-cc machine that placed 10th overall-and its two support aircraft.

Silk scarves and tire sealant compound might seem trifling details in the planning that precedes a desert race. But, the cumulative effect of countless similar items, combined with meticulous machine preparation, form the background to Long Beach Honda’s win in the Mexican 1000.

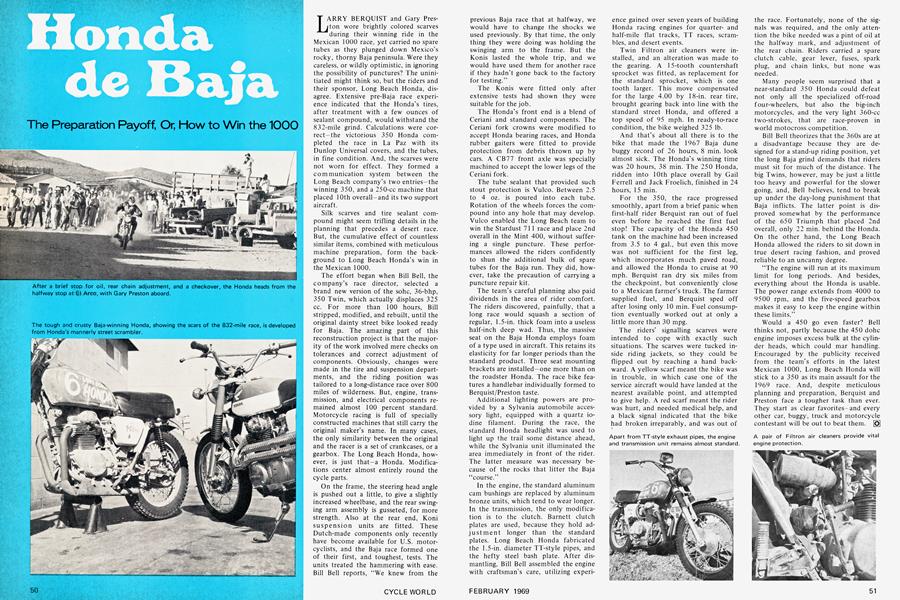

The effort began when Bill Bell, the company’s race director, selected a brand new version of the sohc, 36-bhp, 350 Twin, which actually displaces 325 cc. Lor more than 100 hours, Bill stripped, modified, and rebuilt, until the original dainty street bike looked ready for Baja. The amazing part of this reconstruction project is that the majority of the work involved mere checks on tolerances and correct adjustment of components. Obviously, changes were made in the tire and suspension departments, and the riding position was tailored to a long-distance race over 800 miles of wilderness. But, engine, transmission, and electrical components remained almost 100 percent standard. Motorcycle racing is full of specially constructed machines that still carry the original maker’s name. In many cases, the only similarity between the original and the racer is a set of crankcases, or a gearbox. The Long Beach Honda, however, is just that-a Honda. Modifications center almost entirely round the cycle parts.

On the frame, the steering head angle is pushed out a little, to give a slightly increased wheelbase, and the rear swinging arm assembly is gusseted, for more strength. Also at the rear end, Koni suspension units are fitted. These Dutch-made components only recently have become available for U.S. motorcyclists, and the Baja race formed one of their first, and toughest, tests. The units treated the hammering with ease. Bill Bell reports, “We knew from the previous Baja race that at halfway, we would have to change the shocks we used previously. By that time, the only thing they were doing was holding the swinging arm to the frame. But the Konis lasted the whole trip, and we would have used them for another race if they hadn’t gone back to the factory for testing.”

The Konis were fitted only after extensive tests had shown they were suitable for the job.

The Honda’s front end is a blend of Ceriani and standard components. The Ceriani fork crowns were modified to accept Honda bearing races, and Honda rubber gaiters were fitted to provide protection from debris thrown up by cars. A CB77 front axle was specially machined to accept the lower legs of the Ceriani fork.

The tube sealant that provided such stout protection is Vulco. Between 2.5 to 4 oz. is poured into each tube. Rotation of the wheels forces the compound into any hole that may develop. Vulco enabled the Long Beach team to win the Stardust 711 race and place 2nd overall in the Mint 400, without suffering a single puncture. These performances allowed the riders confidently to shun the additional bulk of spare tubes for the Baja run. They did, however, take the precaution of carrying a puncture repair kit.

The team’s careful planning also paid dividends in the area of rider comfort. The riders discovered, painfully, that a long race would squash a section of regular, 1.5-in. thick foam into a useless half-inch deep wad. Thus, the massive seat on the Baja Honda employs foam of a type used in aircraft. This retains its elasticity for far longer periods than the standard product. Three seat mounting brackets are installed—one more than on the roadster Honda. The race bike features a handlebar individually formed to Berquist/Preston taste.

Additional lighting powers are provided by a Sylvania automobile accessory light, equipped with a quartz iodine filament. During the race, the standard Honda headlight was used to light up the trail some distance ahead, while the Sylvania unit illuminated the area immediately in front of the rider. The latter measure was necessary because of the rocks that litter the Baja “course.”

In the engine, the standard aluminum cam bushings are replaced by aluminum bronze units, which tend to wear longer. In the transmission, the only modification is to the clutch. Barnett clutch plates are used, because they hold adjustment longer than the standard plates. Long Beach Honda fabricated the 1.5-in. diameter TT-style pipes, and the hefty steel bash plate. After dismantling, Bill Bell assembled the engine with craftsman’s care, utilizing experience gained over seven years of building Honda racing engines for quarterand half-mile flat tracks, TT races, scrambles, and desert events.

Twin Filtron air cleaners were installed, and an alteration was made to the gearing. A 15-tooth countershaft sprocket was fitted, as replacement for the standard sprocket, which is one tooth larger. This move compensated for the large 4.00 by 18-in. rear tire, brought gearing back into line with the standard street Honda, and offered a top speed of 95 mph. In ready-to-race condition, the bike weighed 325 lb.

And that’s about all there is to the bike that made the 1967 Baja dune buggy record of 26 hours, 8 min. look almost sick. The Honda’s winning time was 20 hours, 38 min. The 250 Honda, ridden into 10th place overall by Gail Ferrell and Jack Froelich, finished in 24 hours, 15 min.

For the 350, the race progressed smoothly, apart from a brief panic when first-half rider Berquist ran out of fuel even before he reached the first fuel stop! The capacity of the Honda 450 tank on the machine had been increased from 3.5 to 4 gal., but even this move was not sufficient for the first leg, which incorporates much paved road, and allowed the Honda to cruise at 90 mph. Berquist ran dry six miles from the checkpoint, but conveniently close to a Mexican farmer’s truck. The farmer supplied fuel, and Berquist sped off after losing only 10 min. Fuel consumption eventually worked out at only a little more than 30 mpg.

The riders’ signalling scarves were intended to cope with exactly such situations. The scarves were tucked inside riding jackets, so they could be flipped out by reaching a hand backward. A yellow scarf meant the bike was in trouble, in which case one of the service aircraft would have landed at the nearest available point, and attempted to give help. A red scarf meant the rider was hurt, and needed medical help, and a black signal indicated that the bike had broken irreparably, and was out of the race. Fortunately, none of the signals was required, and the only attention the bike needed was a pint of oil at the halfway mark, and adjustment of the rear chain. Riders carried a spare clutch cable, gear lever, fuses, spark plug, and chain links, but none was needed.

Many people seem surprised that a near-standard 350 Honda could defeat not only all the specialized off-road four-wheelers, but also the big-inch motorcycles, and the very light 360-cc two-strokes, that are race-proven in world motocross competition.

Bill Bell theorizes that the 360s are at a disadvantage because they are designed for a stand-up riding position, yet the long Baja grind demands that riders must sit for much of the distance. The big Twins, however, may be just a little too heavy and powerful for the slower going, and, Bell believes, tend to break up under the day-long punishment that Baja inflicts. The latter point is disproved somewhat by the performance of the 650 Triumph that placed 2nd overall, only 22 min. behind the Honda. On the other hand, the Long Beach Honda allowed the riders to sit down in true desert racing fashion, and proved reliable to an uncanny degree.

“The engine will run at its maximum limit for long periods. And besides, everything about the Honda is usable. The power range extends from 4000 to 9500 rpm, and the five-speed gearbox makes it easy to keep the engine within these limits.”

Would a 450 go even faster? Bell thinks not, partly because the 450 dohc engine imposes excess bulk at the cylinder heads, which could mar handling. Encouraged by the publicity received from the team’s efforts in the latest Mexican 1000, Long Beach Honda will stick to a 350 as its main assault for the 1969 race. And, despite meticulous planning and preparation, Berquist and Preston face a tougher task than ever. They start as clear favorites—and every other car, buggy, truck and motorcycle contestant will be out to beat them. [O]