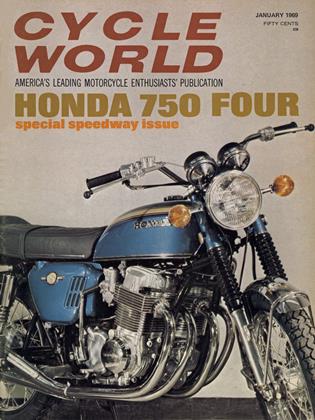

HONDA’S FABULOUS 750 FOUR

Honda Launches the Ultimate Weapon in One-Upmanship — a Magnificent, Musclebound, Racer for the Road.

IF THERE were no Honda motorcycle factory, would anyone believe a 250-cc four-stroke machine that screams to 16,000 rpm? Without Honda, would there be in existence today a five-cylinder 125 four-stroke capable of 18,000 rpm, or a twin-cylinder 50 that will wind to almost 20,000 rpm? The answer, in each case, is a definite "No!" While factories such as Suzuki, Yamaha, MZ, Bridgestone and Kawasaki have poured huge sums of money into development of two-stroke engines, Honda is virtually the only company that, in recent years, has replied with an effective program radically to benefit the four-stroke motorcycle powerplant.

The 250 Six, 125 Five, and 50 Twin are products of Honda's racing and research departments. And, they form a theme that Honda engineers have followed since the company first entered international racing. Stating it simply, Honda likes small cylinders—and many of them.

The thinking behind this multiplication of cylinders is, of course, identical to that which prompts designers of grand prix automobile engines to move from V-8 configurations to 12and 16-cylinder powerplants. There are two basic ways to increase the power of an internal combustion engine. One method is to enlarge piston displacement; the other is to improve the volumetric efficiency of the existing size of engine. The former measure is the least complex, but cannot always be used. In racing, for example, limitations usually are placed on the maximum displacement of engines. And, in motorcycle designs, exceptionally large and heavy power units can be used only at the expense of handling and ridability.

Advantages of using small cylinders, with short piston strokes, lie in the possibility of higher crankshaft rpm, and the consequent increase in the number of power strokes. The proportionately smaller masses of individual pistons, connecting rods, and valve train components enable the engine to operate safely at high speeds, and ensure mechanical reliability and durability. Engines built on these principles have won Honda almost 150 grand prix races, approximately 15 rider's championships, and almost 20 TT victories.

Now, Honda extends the same line of thought into its latest road machine—the fabulous, four-cylinder, ohc, disc-braked 750. Presumably, Honda could have built the 750 as a Twin. Other manufacturers, notably the English factories, produce parallel Twins with total piston displacement of up to 750 cc. And, lovers of big-inch machinery can walk into any HarleyDavidson dealer and order a V-Twin of more than 1200 cc displacement. If Honda built a muscular big Twin, it would doubtless incorporate the factory's famous quality construction, sell at a reasonable price (one of the best bargains in motorcycling today is Honda's 107-mph 450 roadster, available for less than $1000), and go very fast (low-13-sec. standing quarters?).

But, the largest production Twin that has ever left the factory is the 450, a mere stripling, according to the devotees of cubic inches. So, perhaps the revelation that Honda's entry into the prestige machine class is a Four should have come as no great surprise. After all, the factory has never exactly languished in the second best position. It is the world's largest volume producer of motorcycles, but, equally important, has always possessed the knack of building quality into machines built on a quantity basis.

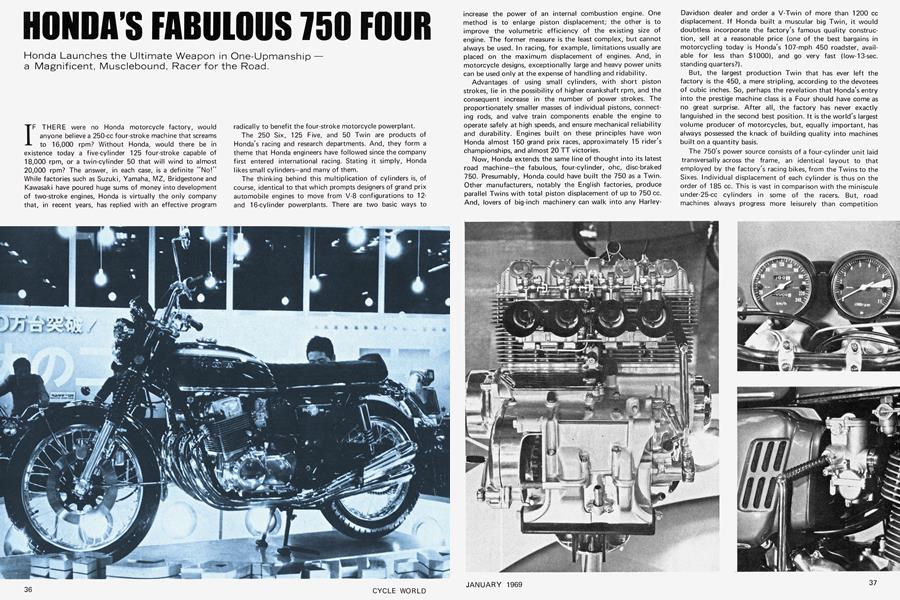

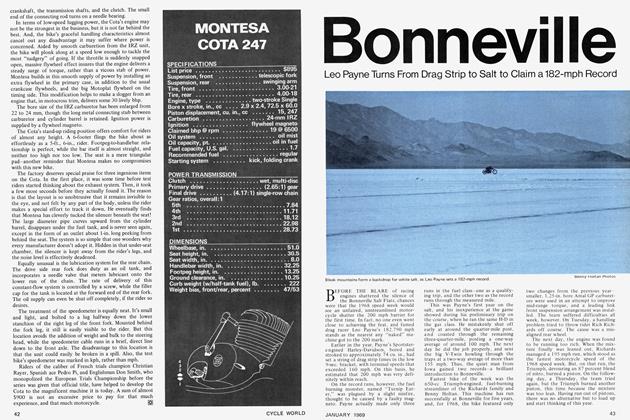

The 750's power source consists of a four-cylinder unit laid transversally across the frame, an identical layout to that employed by the factory's racing bikes, from the Twins to the Sixes. Individual displacement of each cylinder is thus on the order of 185 cc. This is vast in comparison with the miniscule under-25-cc cylinders in some of the racers. But, road machines always progress more leisurely than competition bikes, in the interests of reliability and longevity. Make no mistake, Honda's decade in international motorcycle racing, and its briefer period in grand prix automobile competition, reflect massively on the design of the 750 roadster.

Basic engine and transmission details can be seen in the accompanying diagram. Drive to the single overhead camshaft is by chain from a sprocket located between the two pairs of cylinders. Primary transmission also is by chain, a divergence from Honda's usual practice of employing gears for this task. At the time of writing, it was not known whether the primary drive and camshaft drive chains are of single-row, duplex, or triplex proportions. Each side of the crankshaft features crankpins set at 180 degrees to each other; in other words, when the two outer pistons are at tdc, the inner pair is at bdc. On the left end of the crankshaft, a generator provides power for the electric starter. Again contrary to Honda practice, all main and rod bearings are plain. This surprising departure from more sophisticated roller bearings should enhance reliability, because plain bearings are capable of withstanding heavier loads. But, they do absorb more power through friction than, say, rollers. Maybe Honda is so confident of the 750's power output that it is not concerned about this point.

While some industry experts expected that a single-plate dry clutch might be necessary to handle the 750's musclepower, Honda has retained a conventional multi-plate unit. From the clutch, drive is transferred to the gearbox shafts, the gearbox sprocket, and by a single-row chain to the rear wheel.

Overall engine dimensions are tidily compact for a fourcylinder unit. It measures 20.5 in. across the crankcases, 18.9 in. in length, and is approximately 17.3 in. wide across the cylinder barrels. Honda resorted to several space-saving measures in order to achieve this reduced bulk. The central drive takeoff decreases engine width—a primary drive system mounted on one end of the crankshaft would increase this dimension. The single camshaft is preferred to a dohc layout, which would involve cam covers projecting forward and rearward of the cylinder heads. And, the 750 employs a dry sump lubrication system, a feature almost unique on Honda machinery. Oil is instead contained in a separate tank, mounted beneath the seat. This saves an inch or two beneath the crankcase. The transmission also, following Honda race car practice, features dry sump lubrication.

The engine breathes through four 26-mm Keihin carburetors. All four throttle slides are operated through a drum attached to a shaft, and rotated by a push-pull cable system.

Japanese sources say the bike's power output now has been confirmed at 75 bhp at 9500 rpm. A figure of this order was expected, for Honda's 325-cc Twins produce 36 bhp at 10,500 rpm. However, though such an output had been predicted for the past few months, the reality is nonetheless staggering. After all, not more than 80 bhp is claimed for the three-cylinder MV that in recent years has dominated the 500-cc class of world championship road racing. Comparisons between racing and road machinery usually are misleading. But, in this case, the contrast does indicate the immensity of the 750 Four's potential.

Honda claims that, during tests, the Four has reached a maximum speed of 130 mph, and standing quarter-miles in 12.3 sec. If these figures are correct, they make the bike the world's fastest production motorcycle. That fact alone should be sufficient to fill dealers' books with more than a few advance orders.

At least three major departures have been made from the design of the bike pictured in the first photographs released. The major change is the installation of a hydraulic, single-disc front brake. The bike pictured in last month's Report from Japan featured a twin leading shoe unit that appears similar to those fitted to Honda 450s. The new brake, shown in latest photographs, includes a disc 11.8 in. in diameter, and a handlebar-mounted reservoir for the brake fluid. Previous experience with this type of component leads CYCLE WORLD to believe that it is the most effective form of stopping power that could be fitted to a bike as fast as the Four. This magazine has tested two other machines—a Dunstall 750, and a Rickman Triumph Metisse—that featured similar hydraulically-operated brakes. In each case, the unit proved markedly superior to cable-operated drum brakes, and far smoother in operation. Presumably, the Honda version will offer similar benefits.

Other modifications concern the fuel tank and the exhaust system. The tank first appeared to be lifted from the Honda 450. Now, latest 750s display a more streamlined design. The new tank does, in fact, look somewhat scanty in size, and should ensure many stops for fill-ups if the Honda's potential is used to the full—or as far as speed limits will permit. The exhaust pipes have been given a bright chrome finish, in place of the previous black matt surface. The pipes are fitted with racy-looking reverse cone megaphones.

Visually, the 750 is a meticulously designed, finely balanced mastodon. Overall dimensions of the bike are: height, 44.3 in.; length, 87.0 in.; width, 31.5 in.; and wheelbase, 58.2 in. The double cradle frame is the first of this type that Honda has used. The seat, although it looks scanty, actually offers generous room, while the handlebar strikes a happy compromise. It's not too high to make fast riding excessively awkward, yet provides enough leverage for easy walking-pace control. With two megaphone-shaped silencers ranged along each side of the machine, its rear end is decidedly busy. Thus, rear footpegs are mounted solidly to the outer silencers.

Instrumentation consists of a tachometer reading to 11,000 rpm, and a 240-kph (150 mph) speedometer that incorporates an odometer. Turn signals also are fitted.

Suspension equipment follows normal Honda procedure—a telescopic fork is fitted at the front, and De Carbon shock absorbers and a swinging arm at the rear. Tires are Dunlop K70s, and the sizes are 3.25-19 at the front, and 4.00-18 at the rear. The rear single leading shoe drum brake is operated by a conventional rod assembly.

And, that is about all that is known about the new Honda, thus far. When will it be available? How much will it cost? April of this year is the earliest that it will be marketed, and, as yet, no price has been announced. The U.S. already is tense with anticipation for the new machine. Since the first announcement of the Four (Report from Japan, CW, Dec. '68), this magazine has been busy answering letters and phone calls from would-be buyers. More than one Honda dealer has complained to CW that advance news of the 750 sent customers rushing to his shop, eager to buy a machine that dealers will not possess for at least several months.

But, the easiest mistake in the world is to rave wildly about a new machine simply because it is new. The final proof of even the most exotic machines lies in the way they ride, how they handle, how long they last. As soon as is humanly possible, CYCLE WORLD will have the new Honda for road test, and report on what it is and does, rather than what it appears to be.