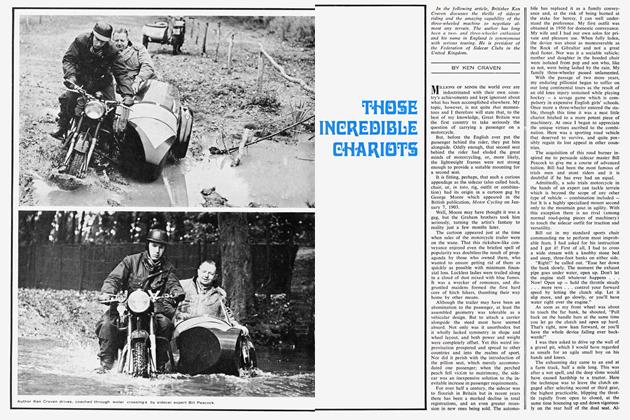

A Sidecar for Touring

The Thunderbolt/Watsonian Combines Speed With Comfort

KEN CRAVEN

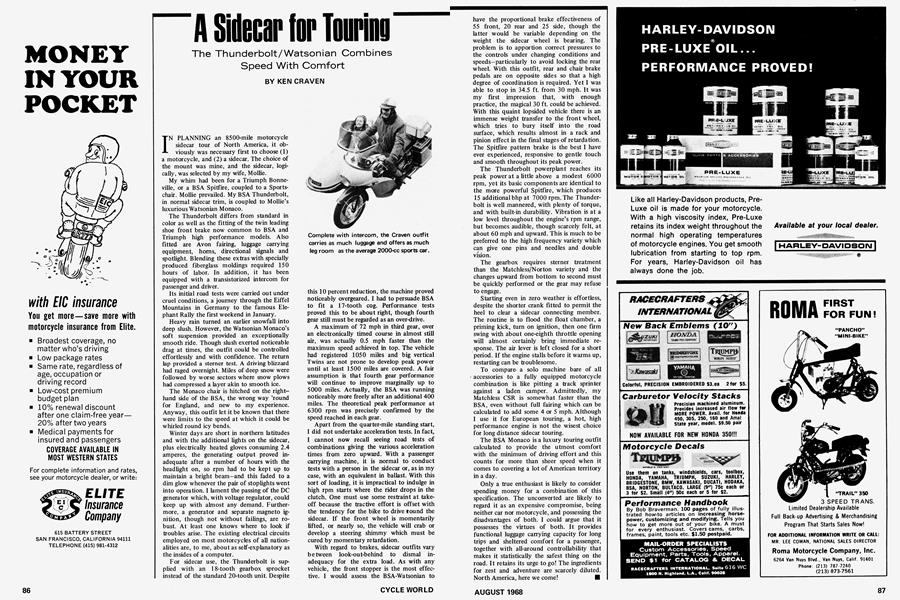

IN PLANNING an 8500-mile motorcycle sidecar tour of North America, it obviously was necessary first to choose (1) a motorcycle, and (2) a sidecar. The choice of the mount was mine, and the sidecar, logically, was selected by my wife, Moffie.

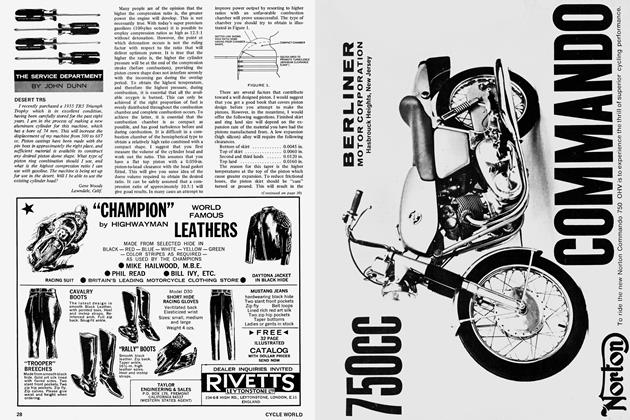

had been for a Triumph Bonneville, or a BSA Spitfire, coupled to a Sportschair. Mollie prevailed. My BSA Thunderbolt, in normal sidecar trim, is coupled to Mollie's luxurious Watsonian Monaco. The Thunderbolt

differs from standard in color as well as the fitting of the twin leading shoe front brake now common to BSA and Triumph high performance models. Also fitted are Avon fairing, luggage carrying equipment, horns, directional signals and spotlight. Blending these extras with specially produced fiberglass moldings required 150 hours of labor. In addition, it has been equipped with a transistorized intercom for passenger and driver. Its initial

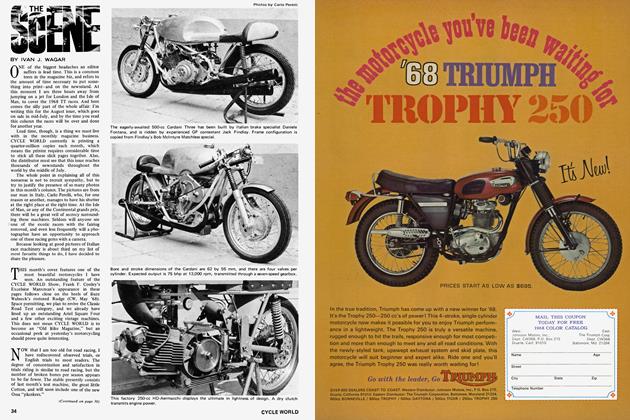

road tests were carried out under cruel conditions, a journey through the Eiffel Mountains in Germany to the famous Elephant Rally the first weekend in January. Heavy rain

turned an earlier snowfall into deep slush. However, the Watsonian Monaco's soft suspension provided an exceptionally smooth ride. Though slush exerted noticeable drag at times, the outfit could be controlled effortlessly and with confidence. The return lap provided a sterner test. A driving blizzard had raged overnight. Miles of deep snow were followed by worse sectors where snow plows had compressed a layer akin to smooth ice. The Monaco

chair is hitched on the righthand side of the BSA, the wrong way 'round for England, and new to my experience. Anyway, this outfit let it be known that there were limits to the speed at which it could be whirled round icy bends. Winter days

are short in northern latitudes and with the additional lights on the sidecar, plus electrically heated gloves consuming 2.4 amperes, the generating output proved inadequate after a number of hours with the headlight on, so rpm had to be kept up to maintain a bright beam-and this faded to a dim glow whenever the pair of stoplights went into operation. I lament the passing of the DC generator which, with voltage regulator, could keep up with almost any demand. Furthermore, a generator and separate magneto ignition, though not without failings, are robust. At least one knows where to look if troubles arise. The existing electrical circuits employed on most motorcycles of all nationalities are, to me, about as self-explanatory as the insides of a computer. For sidecar

use, the Thunderbolt is supplied with an 18-tooth gearbox sprocket instead of the standard 20-tooth unit. Despite this 10

percent reduction, the machine proved noticeably overgeared. I had to persuade BSA to fit a 17-tooth cog. Performance tests proved this to be about right, though fourth gear still must be regarded as an over-drive. A maximum

of 72 mph in third gear, over an electronically timed course in almost still air, was actually 0.5 mph faster than the maximum speed achieved in top. The vehicle had registered 1050 miles and big vertical Twins are not prone to develop peak power until at least 1500 miles are covered. A fair assumption is that fourth gear performance will continue to improve marginally up to 5000 miles. Actually, the BSA was running noticeably more freely after an additional 400 miles. The theoretical peak performance at 6300 rpm was precisely confirmed by the speed reached in each gear. Apart from

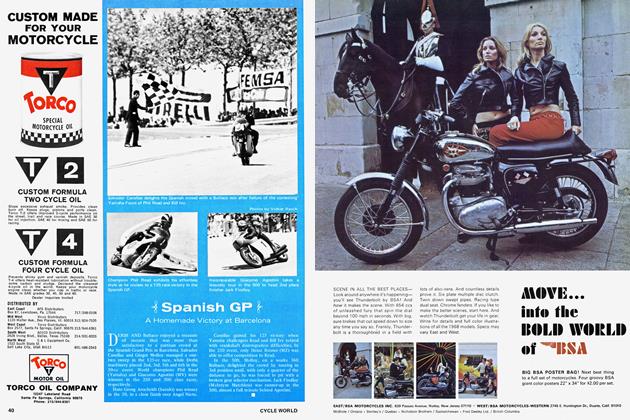

the quarter-mile standing start, I did not undertake acceleration tests. In fact, I cannot now recall seeing road tests of combinations giving the various acceleration times from zero upward. With a passenger carrying machine, it is normal to conduct tests with a person in the sidecar or, as in my case, with an equivalent in ballast. With this sort of loading, it is impractical to indulge in high rpm starts where the rider drops in the clutch. One must use some restraint at takeoff because the tractive effort is offset with the tendency for the bike to drive round the sidecar. If the front wheel is momentarily lifted, or nearly so, the vehicle will crab or develop a steering shimmy which must be cured by momentary retardation. With regard

to brakes, sidecar outfits vary between look-out-behind to dismal inadequacy for the extra load. As with any vehicle, the front stopper is the most effective. I would assess the BSA-Watsonian to 86 86 have the proportional brake effectiveness of 55 front, 20 rear and 25 side, though the latter would be variable depending on the weight the sidecar wheel is bearing. The problem is to apportion correct pressures to the controls under changing conditions and speeds—particularly to avoid locking the rear wheel. With this outfit, rear and chair brake pedals are on opposite sides so that a high degree of coordination is required. Yet I was able to stop in 34.5 ft. from 30 mph. It was my first impression that, with enough practice, the magical 30 ft. could be achieved. With this quaint lopsided vehicle there is an immense weight transfer to the front wheel, which tries to bury itself into the road surface, which results almost in a rack and pinion effect in the final stages of retardation. The Spitfire pattern brake is the best I have ever experienced, responsive to gentle touch and smooth throughout its peak power.

The Thunderbolt powerplant reaches its peak power at a little above a modest 6000 rpm, yet its basic components are identical to the more powerful Spitfire, which produces 15 additionalbhp at 7000 rpm. The Thunderbolt is well mannered, with plenty of torque, and with built-in durability. Vibration i$ at a low level throughout the engine's rpm range, but becomes audible, though scarcely felt, at about 60 mph and upward. This is much to be preferred to the high frequency variety which can give one pins and needles and double vision.

The gearbox requires sterner treatment than the Matchless/Norton variety and the changes upward from bottom to second must be quickly performed or the gear may refuse to engage.

Starting even in zero weather is effortless, despite the shorter crank fitted to permit the heel to clear a sidecar connecting member. The routine is to flood the float chamber, a priming kick, turn on ignition, then one firm swing with about one-eighth throttle opening will almost certainly bring immediate response. The air lever is left closed for a short period. If the engine stalls before it warms up, restarting can be troublesome.

To comparea solo machine bare of all accessories to a fully equipped motorcycle combination is like pitting a track sprinter against a laden camper. Admittedly, my Matchless CSR is somewhat faster than the BSA, even without full fairing which can be calculated to add some 4 or 5 mph. Although I use it for European touring, a hot, high performance engine is not the wisest choice for long distance sidecar touring.

The BSA Monaco is a luxury touring outfit calculated to provide the utmost comfort with the minimum of driving effort and this counts for more than sheer speed when it comes to covering a lot of American territory in a day.

Only a true enthusiast is likely to consider spending money for a combination of this specification. The unconverted are likely to regard it as an expensive compromise, being neither car nor motorcycle, and possessing the disadvantages of both. I could argue that it possesses the virtues of both. It provides functional luggage carrying capacity for long trips and sheltered comfort for a passenger, together with all-around controllability that makes it statistically the safest thing on the road. It retains its urge to go! The ingredients for zest and adventure are scarcely diluted. North America, here we come! ■