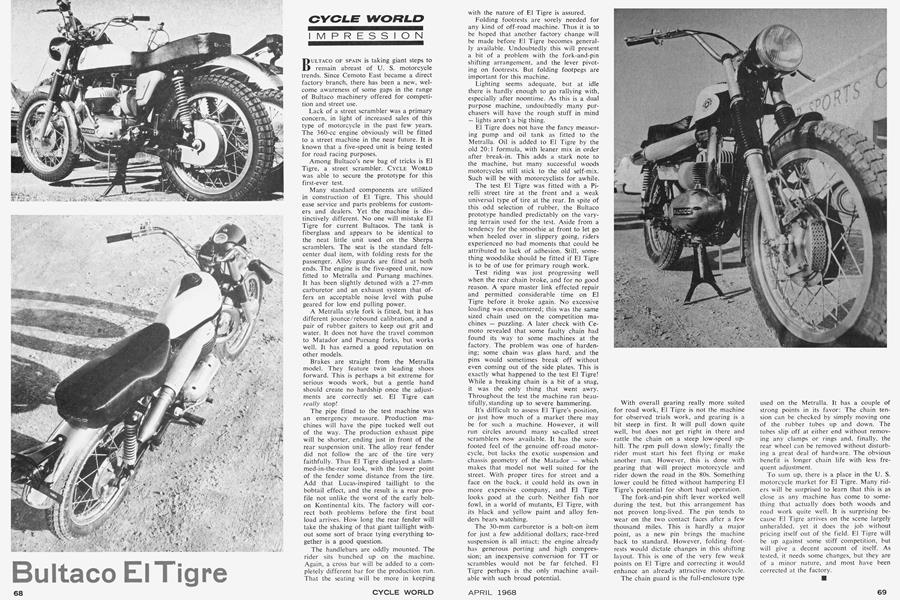

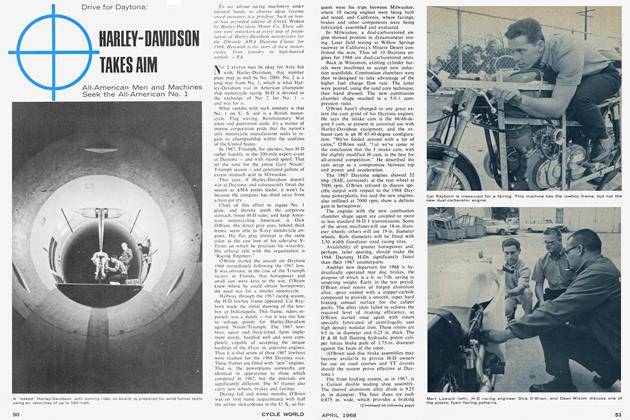

Bultaco Ei Tigre

CYCLE WORLD IMPRESSION

BULTACO OF SPAIN is taking giant steps to remain abreast of U. S. motorcycle trends. Since Cemoto East became a direct factory branch, there has been a new, welcome awareness of some gaps in the range of Bultaco machinery offered for competition and street use.

Lack of a street scrambler was a primary concern, in light of increased sales of this type of motorcycle in the past few years. The 360-cc engine obviously will be fitted to a street machine in the near future. It is known that a five-speed unit is being tested for road racing purposes.

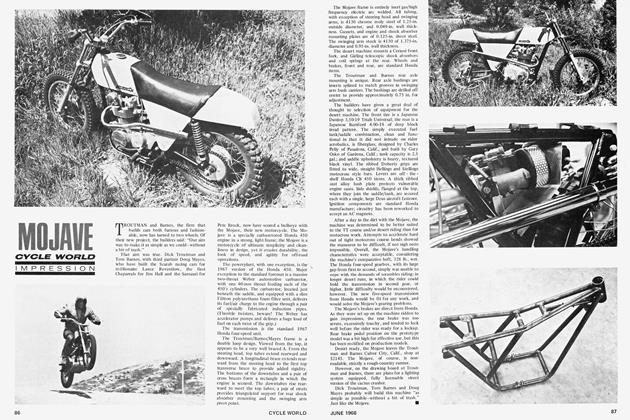

Among Bultaco's new bag of tricks is El Tigre, a street scrambler. CYCLE WORLD was able to secure the prototype for this first-ever test.

Many standard components are utilized in construction of El Tigre. This should ease service and parts problems for customers and dealers. Yet the machine is distinctively different. No one will mistake El Tigre for current Bultacos. The tank is fiberglass and appears to be identical to the neat little unit used on the Sherpa scramblers. The seat is the standard feltcenter dual item, with folding rests for the passenger. Alloy guards are fitted at both ends. The engine is the five-speed unit, now fitted to Metralla and Pursang machines. It has been slightly detuned with a 27-mm carburetor and an exhaust system that offers an acceptable noise level with pulse geared for low end pulling power.

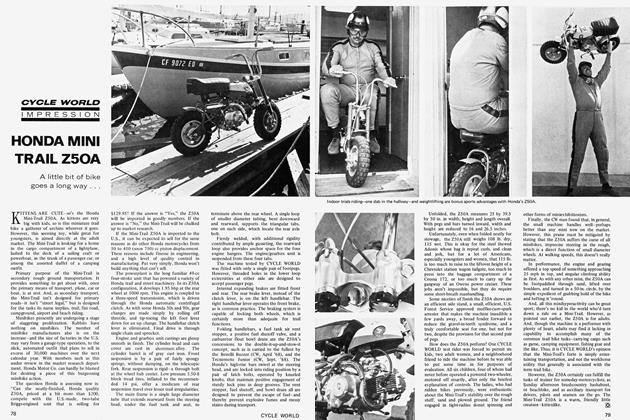

A Metralla style fork is fitted, but it has different jounce/rebound calibration, and a pair of rubber gaiters to keep out grit and water. It does not have the travel common to Matador and Pursang forks, but works well. It has earned a good reputation on other models.

Brakes are straight from the Metralla model. They feature twin leading shoes forward. This is perhaps a bit extreme for serious woods work, but a gentle hand should create no hardship once the adjustments are correctly set. El Tigre can really stop!

The pipe fitted to the test machine was an emergency measure. Production machines will have the pipe tucked well out of the way. The production exhaust pipe will be shorter, ending just in front of the rear suspension unit. The alloy rear fender did not follow the arc of the tire very faithfully. Thus El Tigre displayed a slammed-in-the-rear look, with the lower point of the fender some distance from the tire. Add that Lucas-inspired taillight to the bobtail effect, and the result is a rear profile not unlike the worst of the early bolton Kontinental kits. The factory will correct both problems before the first boat load arrives. How long the rear fender will take the shaking of that giant taillight without some sort of brace tying everything together is a good question.

The handlebars are oddly mounted. The rider sits bunched up on the machine. Again, a cross bar will be added to a completely different bar for the production run. That the seating will be more in keeping with the nature of El Tigre is assured.

Folding footrests are sorely needed for any kind of off-road machine. Thus it is to be hoped that another factory change will be made before El Tigre becomes generally available. Undoubtedly this will present a bit of a problem with the fork-and-pin shifting arrangement, and the lever pivoting on footrests. But folding footpegs are important for this machine.

Lighting seems adequate, but at idle there is hardly enough to go rallying with, especially after noontime. As this is a dual purpose machine, undoubtedly many purchasers will have the rough stuff in mind — lights aren't a big thing.

El Tigre does not have the fancy measuring pump and oil tank as fitted to the Metralla. Oil is added to El Tigre by the old 20:1 formula, with leaner mix in order after break-in. This adds a stark note to the machine, but many successful woods motorcycles still stick to the old self-mix. Such will be with motorcyclists for awhile.

The test El Tigre was fitted with a Pirelli street tire at the front and a weak universal type of tire at the rear. In spite of this odd selection of rubber, the Bultaco prototype handled predictably on the varying terrain used for the test. Aside from a tendency for the smoothie at front to let go when heeled over in slippery going, riders experienced no bad moments that could be attributed to lack of adhesion. Still, something woodslike should be fitted if El Tigre is to be of use for primary rough work.

Test riding was just progressing well when the rear chain broke, and for no good reason. A spare master link effected repair and permitted considerable time on El Tigre before it broke again. No excessive loading was encountered; this was the same sized chain used on the competition machines — puzzling. A later check with Cemoto revealed that some faulty chain had found its way to some machines at the factory. The problem was one of hardening; some chain was glass hard, and the pins would sometimes break off without even coming out of the side plates. This is exactly what happened to the test El Tigre! While a breaking chain is a bit of a snag, it was the only thing that went awry. Throughout the test the machine ran beautifully, standing up to severe hammering.

It's difficult to assess El Tigre's position, or just how much of a market there may be for such a machine. However, it will run circles around many so-called street scramblers now available. It has the surefooted feel of the genuine off-road motorcycle, but lacks the exotic suspension and chassis geometry of the Matador — which makes that model not well suited for the street. With proper tires for street and a face on the back, it could hold its own in more expensive company, and El Tigre looks good at the curb. Neither fish nor fowl, in a world of mutants, El Tigre, with its black and yellow paint and alloy fenders bears watching.

The 3()-mm carburetor is a bolt-on item for just a few additional dollars; race-bred suspension is all intact; the engine already has generous porting and high compression; an inexpensive conversion for TT or scrambles would not be far fetched. El Tigre perhaps is the only machine available with such broad potential. With overall gearing really more suited for road work, El Tigre is not the machine for observed trials work, and gearing is a bit steep in first. It will pull down quite well, but does not get right in there and rattle the chain on a steep low-speed uphill. The rpm pull down slowly; finally the rider must start his feet flying or make another run. However, this is done with gearing that will project motorcycle and rider down the road in the 80s. Something lower could be fitted without hampering El Tigre's potential for short haul operation.

The fork-and-pin shift lever worked well during the test, but this arrangement has not proven long-lived. The pin tends to wear on the two contact faces after a few thousand miles. This is hardly a major point, as a new pin brings the machine back to standard. However, folding footrests would dictate changes in this shifting layout. This is one of the very few weak points on El Tigre and correcting it would enhance an already attractive motorcycle.

The chain guard is the full-enclosure type used on the Metralla. It has a couple of strong points in its favor: The chain tension can be checked by simply moving one of the rubber tubes up and down. The tubes slip off at either end without removing any clamps or rings and, finally, the rear wheel can be removed without disturbing a great deal of hardware. The obvious benefit is longer chain life with less frequent adjustment.

To sum up, there is a place in the U. S. motorcycle market for El Tigre. Many riders will be surprised to learn that this is as close as any machine has come to something that actually does both woods and road work quite well. It is surprising because El Tigre arrives on the scene largely unheralded, yet it does the job without pricing itself out of the field. El Tigre will be up against some stiff competition, but will give a decent account of itself. As tested, it needs some Changes, but they are of a minor nature, and most have been corrected at the factory.