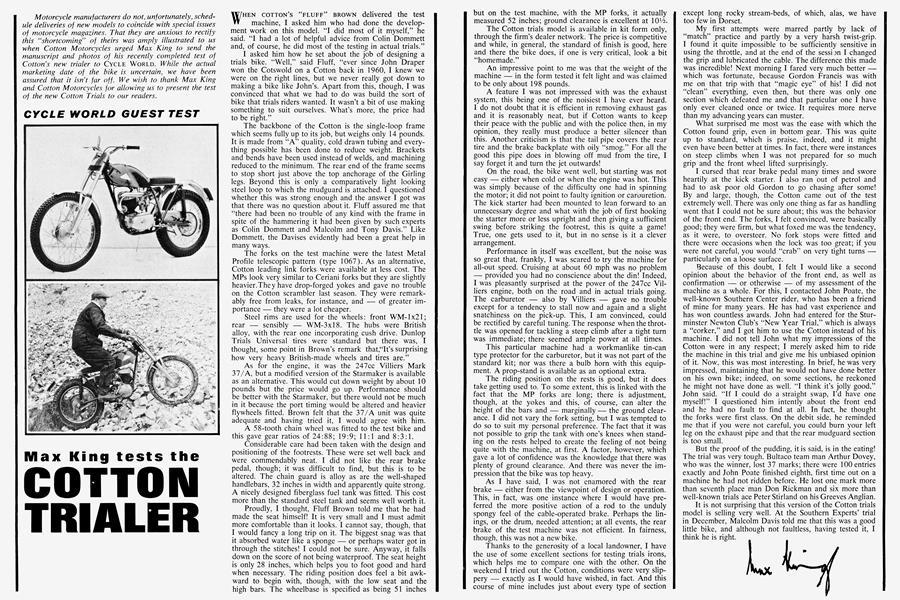

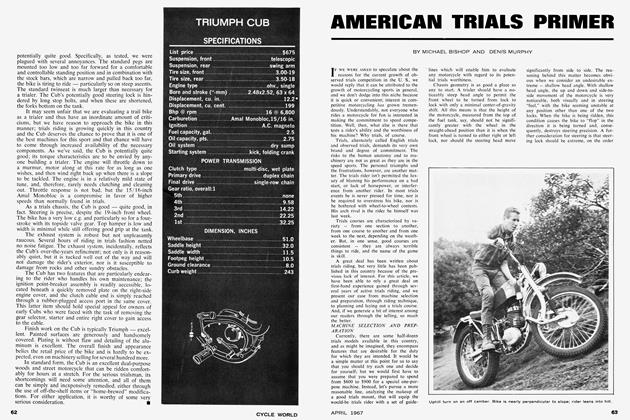

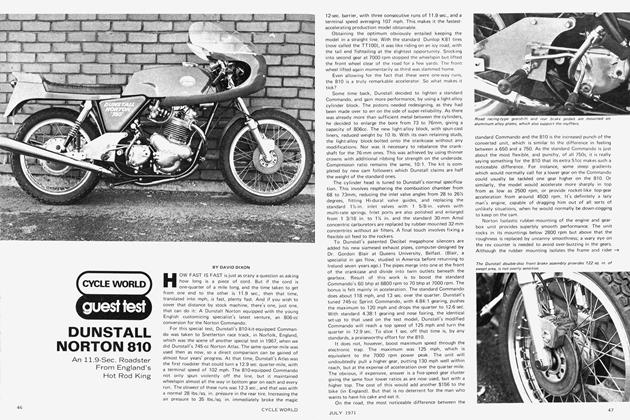

Max King tests the COTTON TRIALER

CYCLE WORLD GUEST TEST

Motorcycle manufacturers do not, unfortunately, schedule deliveries of new models to coincide with special issues of motorcycle magazines. That they are anxious to rectify this “shortcoming” of theirs was amply illustrated to us when Cotton Motorcycles urged Max King to send the manuscript and photos of his recently completed test of Cotton’s new trialer to CYCLE WORLD. While the actual marketing date of the bike is uncertain, we have been assured that it isn’t far off. We wish to thank Max King and Cotton Motorcycles for allowing us to present the test of the new Cotton Trials to our readers.

WHEN COTTON'S “FLUFF'' BROWN delivered the test machine, I asked him who had done the development work on this model. “I did most of it myself,” he said. “I had a lot of helpful advice from Colin Dommett and, of course, he did most of the testing in actual trials.”

I asked him how he set about the job of designing a trials bike. “Well,” said Fluff, “ever since John Draper won the Cotswold on a Cotton back in 1960, I knew we were on the right lines, but we never really got down to making a bike like John’s. Apart from this, though, I was convinced that what we had to do was build the sort of bike that trials riders wanted. It wasn’t a bit of use making something to suit ourselves. What’s more, the price had to be right.”

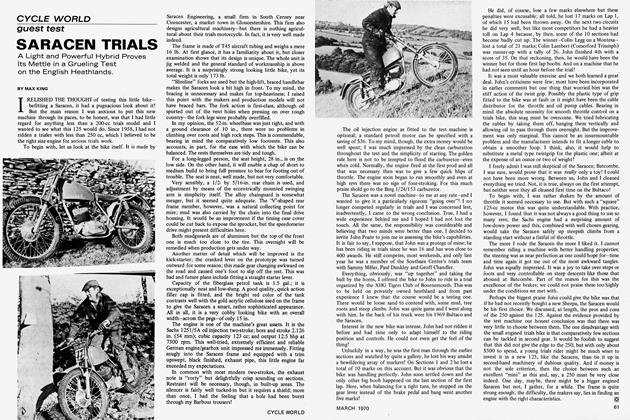

The backbone of the Cotton is the single-loop frame which seems fully up to its job, but weighs only 14 pounds. It is made from “A” quality, cold drawn tubing and everything possible has been done to reduce weight. Brackets and bends have been used instead of welds, and machining reduced to the minimum. The rear end of the frame seems to stop short just above the top anchorage of the Girling legs. Beyond this is only a comparatively light looking steel loop to which the mudguard is attached. I questioned whether this was strong enough and the answer I got was that there was no question about it. Fluff assured me that “there had been no trouble of any kind with the frame in spite of the hammering it had been given by such experts as Colin Dommett and Malcolm and Tony Davis.” Like Dommett, the Davises evidently had been a great help in many ways.

The forks on the test machine were the latest Metal Profile telescopic pattern (type 1067). As an alternative, Cotton leading link forks were available at less cost. The MPs look very similar to Ceriani forks but they are slightly heavier. The y have drop-forged yokes and gave no trouble on the Cotton scrambler last season. They were remarkably free from leaks, for instance, and — of greater importance — they were a lot cheaper.

Steel rims are used for the wheels: front WM-lx21; rear — sensibly — WM-3xl8. The hubs were British alloy, with the rear one incorporating cush drive. Dunlop Trials Universal tires were standard but there was, I thought, some point in Brown’s remark that,“It’s surprising how very heavy British-made wheels and tires are.”

As for the engine, it was the 247cc Villiers Mark 37/A, but a modified version of the Starmaker is available as an alternative. This would cut down weight by about 10 pounds but the price would go up. Performance should be better with the Starmaker, but there would not be much in it because the port timing would be altered and heavier flywheels fitted. Brown felt that the 37/A unit was quite adequate and having tried it, I would agree with him.

A 58-tooth chain wheel was fitted to the test bike and this gave gear ratios of 24:88; 19:9; 11:1 and 8:3:1.

Considerable care had been taken with the design and positioning of the footrests. These were set well back and were commendably neat. I did not like the rear brake pedal, though; it was difficult to find, but this is to be altered. The chain guard is alloy as are the well-shaped handlebars, 32 inches in width and apparently quite strong. A nicely designed fiberglass fuel tank was fitted. This cost more than the standard steel tank and seems well worth it.

Proudly, I thought, Fluff Brown told me that he had made the seat himself! It is very small and I must admit more comfortable than it looks. I cannot say, though, that I would fancy a long trip on it. The biggest snag was that it absorbed water like a sponge — or perhaps water got in through the stitches! I could not be sure. Anyway, it falls down on the score of not being waterproof. The seat height is only 28 inches, which helps you to foot good and hard when necessary. The riding position does feel a bit awkward to begin with, though, with the low seat and the high bars. The wheelbase is specified as being 51 inches but on the test machine, with the MP forks, it actually measured 52 inches; ground clearance is excellent at lOVi.

The Cotton trials model is available in kit form only, through the firm’s dealer network. The price is competitive and while, in general, the standard of finish is good, here and there the bike does, if one is very critical, look a bit “homemade.”

An impressive point to me was that the weight of the machine — in the form tested it felt light and was claimed to be only about 198 pounds.

A feature I was not impressed with was the exhaust system, this being one of the noisiest I have ever heard. I do not doubt that it is efficient in removing exhaust gas and it is reasonably neat, but if Cotton wants to keep their peace with the public and with the police then, in my opinion, they really must produce a better silencer than this. Another criticism is that the tail pipe covers the rear tire and the brake backplate with oily “smog.” For all the good this pipe does in blowing off mud from the tire, I say forget it and turn the jet outwards!

On the road, the bike went well, but starting was not easy — either when cold or when the engine was hot. This was simply because of the difficulty one had in spinning the motor; it did not point to faulty ignition or carouretion. The kick starter had been mounted to lean forward to an unnecessary degree and what with the job of first hooking the starter more or less upright and then giving a sufficient swing before striking the footrest, this is quite a game! True, one gets used to it, but in no sense is it a clever arrangement.

Performance in itself was excellent, but the noise was so great that, frankly, I was scared to try the machine for all-out speed. Cruising at about 60 mph was no problem — provided you had no conscience about the din! Indeed, I was pleasantly surprised at the power of the 247cc Villiers engine, both on the road and in actual trials going. The carburetor — also by Villiers — gave no trouble except for a tendency to stall now and again and a slight snatchiness on the pick-up. This, I am convinced, could be rectified by careful tuning. The response when the throttle was opened for tackling a steep climb after a tight turn was immediate; there seemed ample power at all times.

This particular machine had a workmanlike tin-can type protector for the carburetor, but it was not part of the standard kit; nor was there a bulb horn with this equipment. A prop-stand is available as an optional extra.

The riding position on the rests is good, but it does take getting used to. To some extent, this is linked with the fact that the MP forks are long; there is adjustment, though, at the yokes and this, of course, can alter the height of the bars and — marginally — the ground clearance. I did not vary the fork setting, but I was tempted to do so to suit my personal preference. The fact that it was not possible to grip the tank with one’s knees when standing on the rests helped to create the feeling of not being quite with the machine, at first. A factor, however, which gave a lot of confidence was the knowledge that there was plenty of ground clearance. And there was never the impression that the bike was top heavy.

As I have said, I was not enamored with the rear brake — either from the viewpoint of design or operation. This, in fact, was one instance where I would have preferred the more positive action of a rod to the unduly spongy feel of the cable-operated brake. Perhaps the linings, or the drum, needed attention; at all events, the rear brake of the test machine was not efficient. In fairness, though, this was not a new bike.

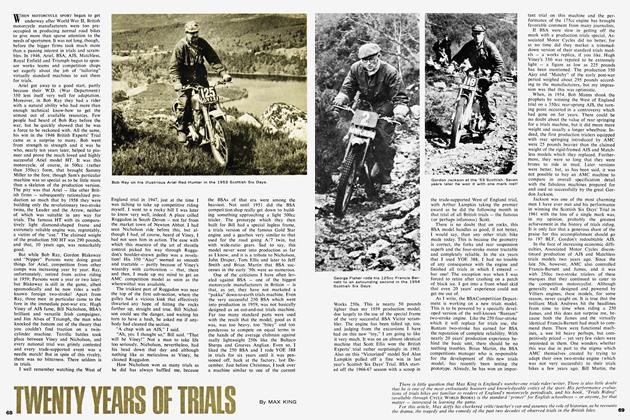

Thanks to the generosity of a local landowner, I have the use of some excellent sections for testing trials irons, which helps me to compare one with the other. On the weekend I tried out the Cotton, conditions were very slippery — exactly as I would have wished, in fact. And this course of mine includes just about every type of section except long rocky stream-beds, of which, alas, we have too few in Dorset.

My first attempts were marred partly by lack of “match” practice and partly by a very harsh twist-grip. I found it quite impossible to be sufficiently sensitive in using the throttle, and at the end of the sessi an I changed the grip and lubricated the cable. The difference this made was incredible! Next morning I fared very much better — which was fortunate, because Gordon Francis was with me on that trip with that “magic eye” of his! I did not “clean” everything, even then, but there was only one section which defeated me and that particular one I have only ever cleaned once or twice. It requires more nerve than my advancing years can muster.

What surprised me most was the ease with which the Cotton found grip, even in bottom gear. This was quite up to standard, which is praise, indeed, and it might even have been better at times. In fact, there were instances on steep climbs when I was not prepared for so much grip and the front wheel lifted surprisingly.

I cursed that rear brake pedal many times and swore heartily at the kick starter. I also ran out of petrol and had to ask poor old Gordon to go chasing after some! By and large, though, the Cotton came out of the test extremely well. There was only one thing as far as handling went that I could not be sure about; this was the behavior of the front end. The forks, I felt convinced, were basically good; they were firm, but what foxed me was the tendency, as it were, to oversteer. No fork stops were fitted and there were occasions when the lock was too great; if you were not careful, you would “crab” on very tight turns — particularly on a loose surface.

Because of this doubt, I felt I would like a second opinion about the behavior of the front end, as well as confirmation — or otherwise — of my assessment of the machine as a whole. For this, I contacted John Poate, the well-known Southern Center rider, who has been a friend of mine for many years. He has had vast experience and has won countless awards. John had entered for the Sturminster Newton Club’s “New Year Trial,” which is always a “corker,” and I got him to use the Cotton instead of his machine. I did not tell John what my impressions of the Cotton were in any respect; I merely asked him to ride the machine in this trial and give me his unbiased opinion of it. Now, this was most interesting. In brief, he was very impressed, maintaining that he would not have done better on his own bike; indeed, on some sections, he reckoned he might not have done as well. “I think it’s jolly good,” John said. “If I could do a straight swap, I’d have one myself!” I questioned him intently about the front end and he had no fault to find at all. In fact, he thought the forks were first class. On the debit side, he reminded me that if you were not careful, you could burn your left leg on the exhaust pipe and that the rear mudguard section is too small.

But the proof of the pudding, it is said, is in the eating! The trial was very tough. Bultaco team man Arthur Dovey, who was the winner, lost 37 marks; there were 100 entries exactly and John Poate finished eighth, first time out on a machine he had not ridden before. He lost one mark more than seventh place man Don Rickman and six more than well-known trials ace Peter Stirland on his Greeves Anglian.

It is not surprising that this version of the Cotton trials model is selling very well. At the Southern Experts’ trial in December, Malcolm Davis told me that this was a good little bike, and although not faultless, having tested it, I