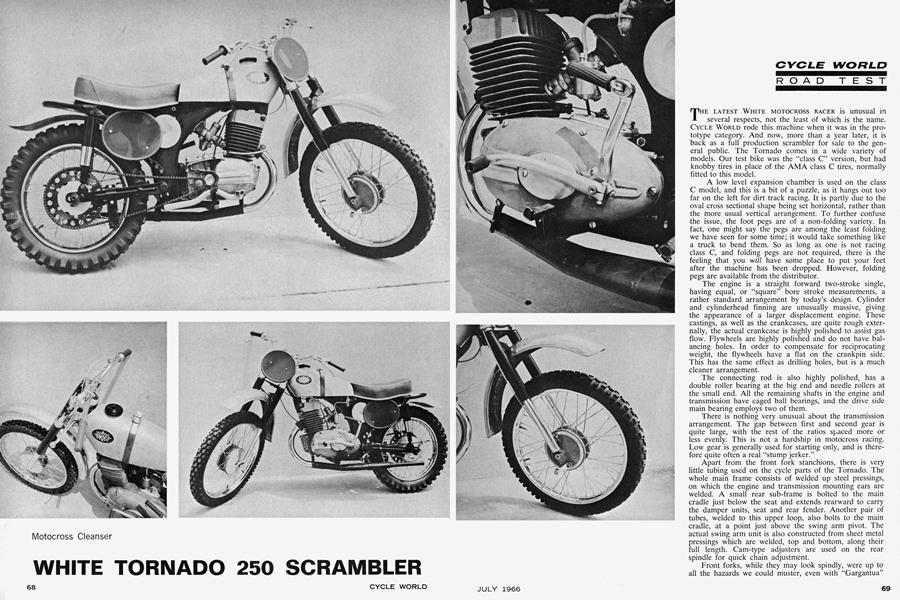

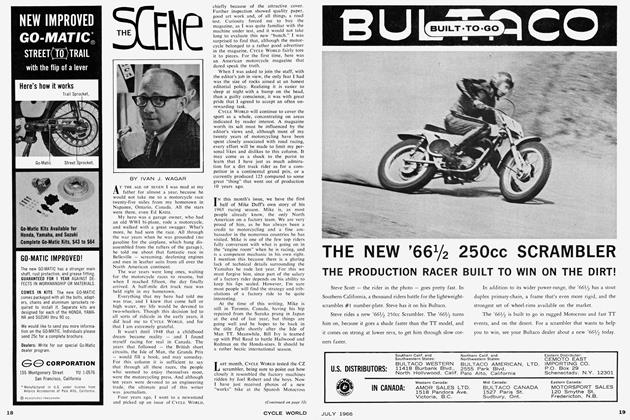

WHITE TORNADO 250 SCRAMBLER

Motocross Cleanser

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

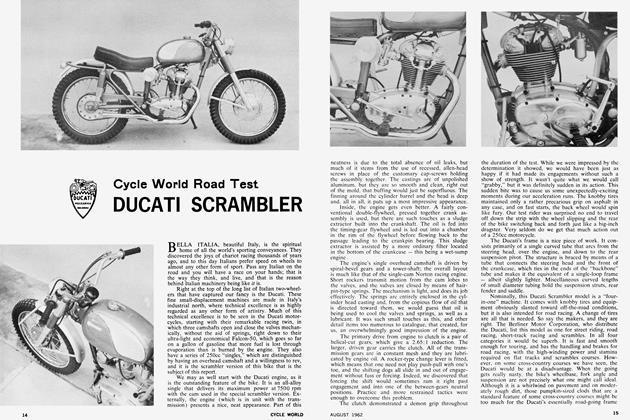

THE LATEST WHITE MOTOCROSS RACER is unusual in several respects, not the least of which is the name. CYCLE WORLD rode this machine when it was in the prototype category. And now, more than a year later, it is back as a full production scrambler for sale to the general public. The Tornado comes in a wide variety of models. Our test bike was the "class C" version, but had knobby tires in place of the AMA class C tires, normally fitted to this model.

A low level expansion chamber is used on the class C model, and this is a bit of a puzzle, as it hangs out too far on the left for dirt track racing. It is partly due to the oval cross sectional shape being set horizontal, rather than the more usual vertical arrangement. To further confuse the issue, the foot pegs are of a non-folding variety. In fact, one might say the pegs are among the least folding we have seen for some time; it would take something like a truck to bend them. So as long as one is not racing class C, and folding pegs are not required, there is the feeling that you will have some place to put your feet after the machine has been dropped. However, folding pegs are available from the distributor.

The engine is a straight forward two-stroke single, having equal, or “square” bore stroke measurements, a rather standard arrangement by today’s design. Cylinder and cylinderhead finning are unusually massive, giving the appearance of a larger displacement engine. These castings, as well as the crankcases, are quite rough externally, the actual crankcase is highly polished to assist gas flow. Flywheels are highly polished and do not have balancing holes. In order to compensate for reciprocating weight, the flywheels have a flat on the crankpin side. This has the same effect as drilling holes, but is a much cleaner arrangement.

The connecting rod is also highly polished, has a double roller bearing at the big end and needle rollers at the small end. All the remaining shafts in the engine and transmission have caged ball bearings, and the drive side main bearing employs two of them.

There is nothing very unusual about the transmission arrangement. The gap between first and second gear is quite large, with the rest of the ratios spaced more or less evenly. This is not a hardship in motocross racing. Low gear is generally used for starting only, and is therefore quite often a real “stump jerker.”

Apart from the front fork stanchions, there is very little tubing used on the cycle parts of the Tornado. The whole main frame consists of welded up steel pressings, on which the engine and transmission mounting ears are welded. A small rear sub-frame is bolted to the main cradle just below the seat and extends rearward to carry the damper units, seat and rear fender. Another pair of tubes, welded to this upper loop, also bolts to the main cradle, at a point just above the swing arm pivot. The actual swing arm unit is also constructed from sheet metal pressings which are welded, top and bottom, along their full length. Cam-type adjusters are used on the rear spindle for quick chain adjustment.

Front forks, while they may look spindly, were up to all the hazards we could muster, even with “Gargantua” riding. Fork travel is sufficient to give a comfortable ride over rough terrain. In fact, with the wheels and tires we were using, the Tornado handled as might be expected from a good motocross machine. The handlebars are the opposite extreme from the last pair we disliked and, without any doubt, these set some sort of record for being the world’s worst. Fortunately, good bars to suit individual riders are easily obtainable, so this is not a permanent handicap.

If the handlebar situation can be overcome, the steering is precise and everything behaves well under hard going. The seat is comfortable and the brakes are adequate for serious competition. We do not like the rear brake pedal arrangement, for safety reasons, because the pedal arm passes over the footpeg, rather than under. If brake fade should occur during a race, or if lining wear is excessive, the pedal will simply bottom on the peg. The result would be no rear brake.

There is a touch of old-world craftsmanship in the fenders, which are still hand formed, and the zinc galvanized gas tank is held on by a leather strap and buckle, making the tank quickly removable.

Some confusion seems to exist regarding the origin of White motorcycles. It has been explained something like this: various parts come from several different sections of Europe — Bosch electrics are from Germany, wheels are made in Austria, and so on. The motorcycle is assembled by Csepel in Hungary, one of Europe’s largest industrial plants. This, at least, applies to the Tornado we tested; other models bearing the White emblem are produced in other European countries.

Watching television commercials, we find the White Tornado is supposed to clean up everything in sight. This one may clean house; it is too soon to say for sure. One did put in a good performance at a recent motocross, until a broken chain ended things. ■

WHITE TORNADO

$745