Torpedoing the Time Barrier

J. L. BEARDSLEY

SINCE THE Olympic Games of Ancient Greece first lit the fires of sporting rivalry among men, becoming the fastest, the strongest, or the best, has spurred the greatest human efforts. But the dawn of the Motor Age brought a fiercer challenge to the eternal question, “How fast?”

To answer it motorcycles have become like rolling rockets built by space age technology; yet they still run on two wheels, driven by guys with nerve, flat-out on top of a hot engine and racing the Grim Reaper for a new record.

The men who first put a motor into a bicycle frame half a century ago had to start from scratch, and the lessons they learned by trial-and-error were first proven in speed tests on the roads and beaches. Getting these fragile machines to run at all was a problem, but to make them run fast took ingenuity and a lot of faith.

The first American to set a flying mile record was C. H. Metz, whose Orient “Motor Bicycles” were among the first made. His mile at Staten Island, New York, in 1 minute 10.4 seconds was over the world mark of 1902, held by Maurice Fournier, of France, at 1:05.6.

But two American engineers were also experimenting with motorcycles in 1902. One was Oscar Hedstrom, a noted bicycle racer, who joined in partnership with George M. Hendee, manufacturer of the Indian bicycle at Springfield, Mass., to build a motor-bike Hedstrom had perfected. Tn a bold bid for publicity, Hedstrom rode one of the new creations in a mile run at Ormond Beach, Florida in 1903 and clocked 1:03.2 seconds, which was claimed as a world record for medium-weight machines of 3 horsepower, and the racing saga of the Indians had begun.

Another builder, whose name would one day become a legend, was throwing his hat into the ring — Glenn Curtiss, famed aviator, inventor, and plane manufacturer. In 1903, Curtiss put a one-cylinder motorbike he’d built in his shop at Hammondsport, New York, to the test. At Providence, Rhode Island, he knocked the American record down to 56.40 seconds — the first mile-a-minute bike in America.

The next year Curtiss had a twin engine job ready and took on W. W. Austin and Oscar Hedstrom, on Indians, in a 10mile match race at Ormond Beach. Curtiss became king of the two-wheelers by beating them in a record 8:54.41 time, with a record mile for the course of 59V2 seconds as well. Later Curtiss scored a sensational mile on his twin of 46.40 seconds, or 77.58 mph, which stood until the Italian star Guippone rode a French Peugeot bike at Ostend, Belgium one kilometer (about 3/5 of a mile) in 27.2 seconds, for 82 mph on July 13, 1905.

Early aviation experimenters had been watching Curtiss and his high-performance air-cooled powerplants used in the line of good motorcycles he built in his Hammondsport factory. Captain Tom Baldwin, noted dirigible designer, commissioned him to build a compact motor to power a small dirigible, and it was completed in 1906 — a neat 40 hp V-8. For testing he mounted the engine in a long steel frame carried on two light automobile wire wheels front and rear, and with a solid shaft drive, it had to be towed 30 miles an hour before starting. In a day of 7 to 10 hp motorcycles, this monstrosity got a lot of attention at the Ormond Beach Speed Carnival, in Florida, in January, 1907.

On the 23rd, Curtiss was ready to fire up his creation for a try at the absolute speed record for motorcycles. A four-mile course was laid out, special timers selected, and Curtiss barreled through a mile that left judges, timers, and spectators in a

state of shock. He had rocketed through in 26.40 seconds! Five timers had caught this fantastic run at 136.36 mph, and all swore to its accuracy ever afterward.

The Rules Committee refused to accept it as official due to “the motor not being standard.” If it had been confirmed, they could have tossed the record book into cold storage for the next 23 years — it took that long to top it.

By 1909, more powerful machines began to attack the record Curtiss set on his standard twin of 46.40, and the scene changed to Daytona Beach, where William Wray, Jr., on a 14 hp Simplex, made a 45-second mile for a new American mark, but Oscar Hedstrom, also on a Simplex, cut this to 44.6. Riding an unnamed make, Robert Stubbs equaled this time on March 25th; but the same day Walter Goerke rode an Indian to a new kilometer record of 27.8 seconds, and 5 miles in 3:30.0.

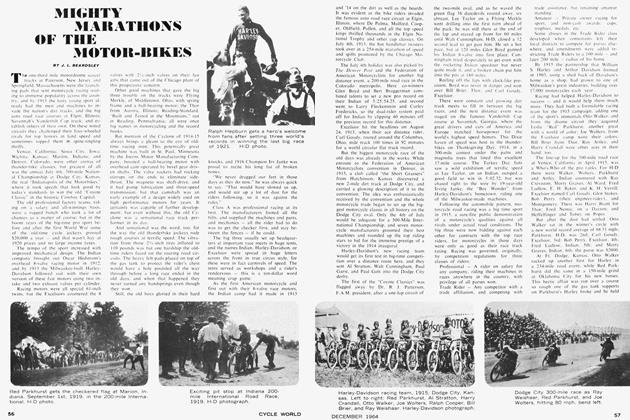

The rise of the Harley-Davidson motorcycle firm, and the intense rivalry with Indian, the other giant of the industry, overshadowed all else in the great road and track championships for the next decade. It was February, 1920, before Harley sent a record-team to Daytona Beach. Fred Ludlow was first to set a new world kilometer mark on a pocketvalve Harley at 102.87 mph on February 13th. Two days later, Leslie “Red” Parkhurst, a H-D racing immortal, wound up a 68 eu. in. 8-valve race bike for a kilometer at 111.98 mph, the fastest speed ever attained by a motorcycle. His mile was a good 110.94, but again the M&ATA (Motorcycle & Allied Trades Association) reverted to technical hair-splitting, and rejected these marks by a motor “above 61inch displacement limits.” Parkhurst then made a solo run on a 61-inch, 8-valve twin, for a new kilometer mark of 103.30 mph, and a mile in 34.89 seconds. Then, with a 61-inch-engined sidecar carrying Fred Ludlow as passenger, he established the first side-hack mile record of 82.10 mph, and this was recognized as a world mark by the FICM in Europe.

In April, 1920, the Indian company rushed Gene Walker to Daytona Beach to restore their prestige in the record books. They were careful to comply with international regulations in making twoway runs, and Walker sent his 61-inch Indian track-burner through the tapes for a 34.70 second average and 103.75 mph. His 5 miles was even better — 108.68 mph. Walker brought the land speed hon-

ors back to the U.S.A., and it was the last world record set at Daytona Beach. In addition, he topped all of Harley’s one way runs, with his best kilometer recorded at 115.79 miles per hour.

European competitors concentrated on kilometer runs, and the famous Brooklands Speedway in England was a center of record attempts on both two and four wheels in the 1920’s. The kilometer was used almost exclusively in European record runs, but for clarity is here given in equivalent miles per hour. Two English riders, Freddie Dixon on a souped-up Harley at 106.20 mph, and an engineer named Temple, on a lOOOcc Anzani, at 108.68 mph, were the next kings of absolute speed on motorcycles in 1923.

Continental speed star Bert LeVack next rose to fame, riding an English lOOOcc Brough-Superior at the Arpajon Speedway in France, where he shot the world mark up to 118.75 mph on July 7, 1924. At the same place in 1925, Paul Anderson rode a 61-inch Indian in a two-way, electrically-timed record assault that figured out to 135.71 mph, which the Motorcycle Club of France hailed as a new mark. But the governing International Motorcycle Federation took a dim view of the timing system and refused to confirm it. This may have been a great injustice, for the 61-inch Indian race jobs of that day were good for this on the straightaway, as proved by Johnny Seymour at Daytona Beach on January 12, 1926. The great Indian star rocketed to a 30.50-inch record kilometer mark of 112.63 mph; and his 61-inch run was a smashing 132.01 mph, both official AMA records.

In Europe, England’s Joe Baldwin and Bert LeVack were rivals who escalated the record up to 129.07 mph in a succession of great performances by each over a four-year period. But in 1930 Germany had a real two-wheel speed champ in Ernst Henne, who began by riding a 750cc supercharged BMW on a road near Ingolstadt, Bavaria, at an official 134.58 mph, for a genuine world mark.

He was immediately challenged by England’s Joe Wright, who rode a JAP-Zenith (JAP were the initials of designer J. A. Prestwich) and on August 31, 1930,

racked up a 137.30 mph record. Henne came back three weeks later to up it to 137.75. The British engineers Temple and Osborn spent a year re-working the JAP engine, and on a course in Ireland, Wright set a new motorcycle mark of 150.74 mph on November 6, 1931.

Henne and the BMW factory experts spent exactly one more year preparing the supercharged German annihilator for another blast-off on November 3, 1932. On a course near Tat, Hungary, Henne raised it to 151.86 mph. He later boosted it to 153.04 mph. But Ernst Henne was never satisfied. Riding on an Autobahn, in Germany, Henne pushe’d the land speed to 159 and finally to 169.13 in 1936. This lasted only until April 17, 1937, when Eric Farnihough, an English schoolteacher with a yen for speed, zoomed over a road near Guyon, France, on a lOOOcc BroughSuperior, at a record 169.75 mph.

It was about this time that HarleyDavidson sent their star Joe Petrali to Daytona Beach, with a 45-inch twin and a 61-inch OHV streamliner. Petrali scorched the sand with a 136.183 speed for a new official AMA record on the streamliner, said to be still a Daytona course record. This famous machine is on exhibit at the Museum of Speed in Daytona Beach, as well as part of Gene Walker’s 1920 Indian record bike. Then in October the noted Italian, Piero Taruffi, roared over the Brescia-Milan Autostrada on a streamlined Güera, just one kilometer an hour better than Farnihough had done.

The record-smashing year of 1937 ended with Ernst Henne in a fantastic ride against time. After shattering all existing world records at 173.64 mph, Henne crawled out of the torpedo shell and announced he was through with all competition riding. He had set seven absolute speed records — more than any other man before or since — and his latest one stood for over 13 years!

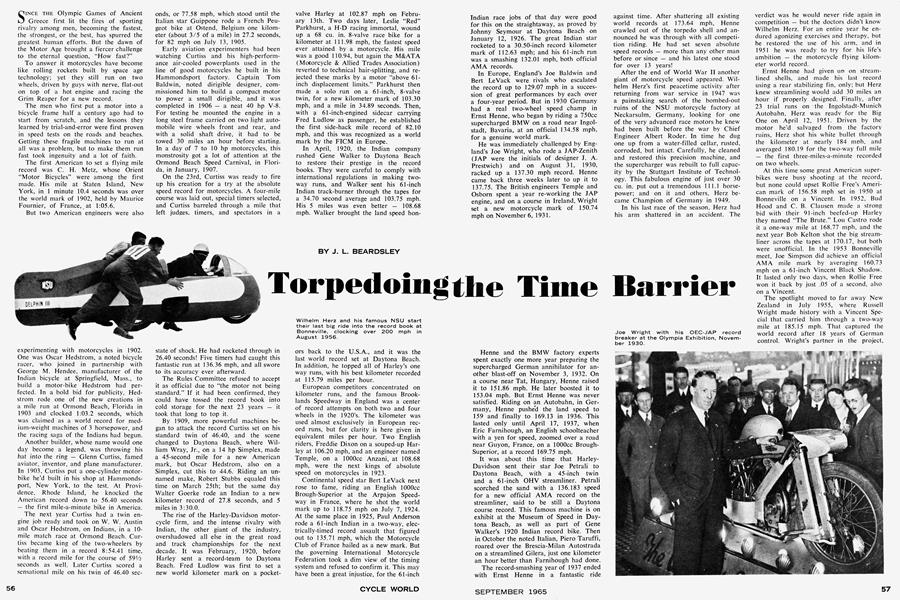

After the end of World War II another giant of motorcycle speed appeared. Wilhelm Herz’s first peacetime activity after returning from war service in 1947 was a painstaking search of the bombed-out ruins of the NSU motorcycle factory at Neckarsulm, Germany, looking for one of the very advanced race motors he knew had been built before the war by Chief Engineer Albert Roder. In time he dug one up from a water-filled cellar, rusted, corroded, but intact. Carefully, he cleaned and restored this precision machine, and the supercharger was rebuilt to full capacity by the Stuttgart Institute of Technology. This fabulous engine of just over 30 eu. in. put out a tremendous 111.1 horsepower; and on it and others, Herz became Champion of Germany in 1949.

In his last race of the season, Herz had his arm shattered in an accident. The verdict was he would never ride again in competition — but the doctors didn’t know Wilhelm Herz. For an entire year he endured agonizing exercises and therapy, but he restored the use of his arm, and in 1951 he was ready to try for his life’s ambition — the motorcycle flying kilometer world record.

Ernst Henne had given un on streamlined shells, and made his last record using a rear stabilizing fin, only; but Herz knew streamlining would add 30 miles an hour if properly designed. Finally, after 23 trial runs on the Ingolstadt-Munich Autobahn, Herz was ready for the Big One on April 12, 1951. Driven by the motor he’d salvaged from the factory ruins, Herz shot his white bullet through the kilometer at nearly 184 mph, and averaged 180.19 for the two-way full mile — the first three-miles-a-minute recorded on two wheels.

At this time some great American superbikes were busy shooting at the record, but none could upset Rollie Free’s American mark of 156.58 mph set in 1950 at Bonneville on a Vincent. In 1952, Bud Hood and C. B. Clausen made a strong bid with their 91-inch beefed-up Harley they named “The Brute.” Lou Castro rode it a one-way mile at 168.77 mph, and the next year Bob Kelton shot the big streamliner across the tapes at 170.17, but both were unofficial. In the 1953 Bonneville meet, Joe Simpson did achieve an official AMA mile mark by averaging 160.73 mph on a 61-inch Vincent Black Shadow. It lasted only two days, when Rollie Free won it back by just .05 of a second, also on a Vincent.

The spotlight moved to far away New Zealand in July 1955, where Russell Wright made history with a Vincent Special that carried him through a two-way mile at 185.15 mph. That captured the world record after 18 years of German control. Wright’s partner in the project, Robert Burns, hooked a sidecar to the machine and established another world three-wheel mark of 163.06 mph.

But back at Bonneville a trio of raceminded Texans were ready to take aim at the record a few weeks later. Stormy Mangham, former race rider and longtime airline pilot, had built an aerodynamic torpedo body around a Triumph. The 40-inch unblown motor was speedtuned to perfection by Jack Wilson, mechanic for Ft. Worth Triumph dealer Pete Dalio; young Johnny Allen of southwestern racing fame would ride.

But they had to wait until the NSU “invasion” of Bonneville was over. The German firm had sent Wilhelm Herz and H. P. Mueller with two streamliners, the “Dolphin” and a torpedo-shaped machine, the Baum Streamliner. Nearly 100 technicians, newsmen, and executives accompanied the party, and on August 4th, 1956, Wilhelm Herz was first to crack the 200 mile barrier with a new land record of 211.40 mph — both his runs had been in identical times! Mueller, in the NSU Baum also set 38 world class records, and the Germans returned home.

Johnny Allen then climbed into the 15foot, fiberglass shell of the Bonneville Triumph, and zoomed over the same course at a blistering 214.40 mph average for an official AMA record. An accident to the timing clocks in transit to the FIM for checking is said to have prevented this from becoming the first accepted world record by an American in 36 years. The same team, using the same machine, but ridden by Jess Thomas, of Ft. Worth, Texas, achieved a second AMA record of 214.47 mph at the salt beds in 1958.

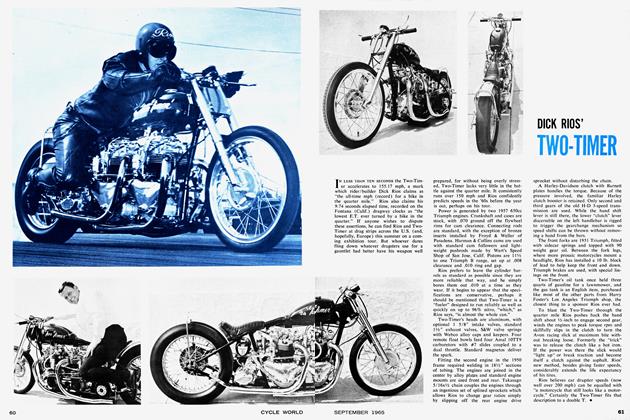

In 1962, a 17-foot needle-nosed shell was built. Johnson Motors Inc., Triumph distributors of Pasadena, California, supplied a 650cc engine for another world record attempt. Joe Dudek, Chief Mechanic, Aero Space Division, North American Aviation, designed the body, and Bill Johnson, of Garden Grove, California, would ride this land-rocket. His aim was good and he climbed to a new land speed of 230.269 mph, accepted by the AMA for Class S-A (streamlined on alcohol-base fuel). As timed by the US AC, an affiliate of FIM, “The Worlds Fastest Motorcycle” proved itself with a kilometer run at 224.56 mph, accepted by the FIM as an official world mark using pump gasoline.

After holding the actual World Flying Mile record for nearly a decade, the Triumph was challenged in 1964 by HarleyDavidson’s Sportster using a streamlined body built by Stormy Mangham, and with Roger Reiman in the missile. A 300 mph goal was announced by the sponsors. This was not achieved, however, so the old, yet-ever-new, question of “How fast can they go?” can’t be answered for another year. But with 70 hp, better streamlining and Goodyear racing tires, the Sportster seems to be a leading contender for a legitimate new two-wheel motorcycle record.