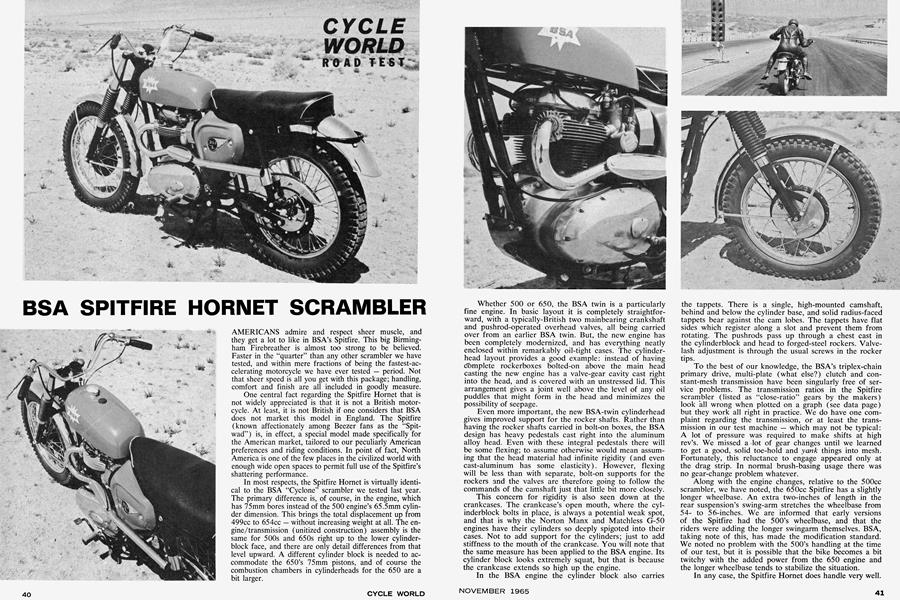

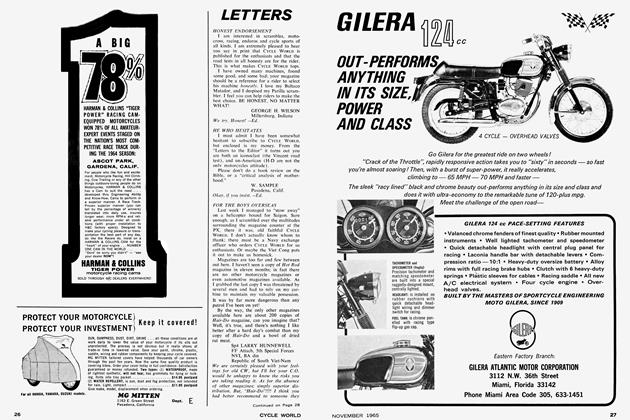

BSA SPITFIRE HORNET SCRAMBLER

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

AMERICANS admire and respect sheer muscle, and they get a lot to like in BSA's Spitfire. This big Birmingham Firebreather is almost too strong to be believed. Faster in the "quarter" than any other scrambler we have tested, and within mere fractions of being the fastest-accelerating motorcycle we have ever tested — period. Not that sheer speed is all you get with this package; handling, comfort and finish are all included in goodly measure.

One central fact regarding the Spitfire Hornet that is not widely appreciated is that it is not a British motorcycle. At least, it is not British if one considers that BSA does not market this model in England. The Spitfire (known affectionately among Beezer fans as the "Spitwad") is, in effect, a special model made specifically for the American market, tailored to our peculiarly American preferences and riding conditions. In point of fact, North America is one of the few places in the civilized world with enough wide open spaces to permit full use of the Spitfire's shattering performance.

In most respects, the Spitfire Hornet is virtually identical to the BSA "Cyclone" scrambler we tested last year. The primary difference is, of course, in the engine, which has 75mm bores instead of the 500 engine's 65.5mm cylinder dimension. This brings the total displacement up from 499cc to 654cc — without increasing weight at all. The engine/transmission (unitized construction) assembly is the same for 500s and 650s right up to the lower cylinderblock face, and there are only detail differences from that level upward. A different cylinder block is needed to accommodate the 650's 75mm pistons, and of course the combustion chambers in cylinderheads for the 650 are a bit larger.

Whether 500 or 650, the BS A twin is a particularly fine engine. In basic layout it is completely straightforward, with a typically-British two mainbearing crankshaft and pushrod-operated overhead valves, all being carried over from an earlier BSA twin. But, the new engine has been completely modernized, and has everything neatly enclosed within remarkably oil-tight cases. The cylinderhead layout provides a good example: instead of having complete rockerboxes bolted-on above the main head casting the new engine has a valve-gear cavity cast right into the head, and is covered with an unstressed lid. This arrangement gives a joint well above the level of any oil puddles that might form in the head and minimizes the possibility of seepage.

Even more important, the new BSA-twin cylinderhead gives improved support for the rocker shafts. Rather than having the rocker shafts carried in bolt-on boxes, the BSA design has heavy pedestals cast right into the aluminum alloy head. Even with these integral pedestals there will be some flexing; to assume otherwise would mean assuming that the head material had infinite rigidity (and even cast-aluminum has some elasticity). However, flexing will be less than with separate, bolt-on supports for the rockers and the valves are therefore going to follow the commands of the camshaft just that little bit more closely.

This concern for rigidity is also seen down at the crankcases. The crankcase's open mouth, where the cylinderblock bolts in place, is always a potential weak spot, and that is why the Norton Manx and Matchless G-50 engines have their cylinders so deeply spigoted into their cases. Not to add support for the cylinders; just to add stiffness to the mouth of the crankcase. You will note that the same measure has been applied to the BSA engine. Its cylinder block looks extremely squat, but that is because the crankcase extends so high up the engine.

In the BSA engine the cylinder block also carries the tappets. There is a single, high-mounted camshaft, behind and below the cylinder base, and solid radius-faced tappets bear against the cam lobes. The tappets have flat sides which register along a slot and prevent them from rotating. The pushrods pass up through a chest cast in the cylinderblock and head to forged-steel rockers. Valvelash adjustment is through the usual screws in the rocker tips.

To the best of our knowledge, the BSA's triplex-chain primary drive, multi-plate (what else?) clutch and constant-mesh transmission have been singularly free of service problems. The transmission ratios in the Spitfire scrambler (listed as "close-ratio" gears by the makers) look all wrong when plotted on a graph (see data page) but they work all right in practice. We do have one complaint regarding the transmission, or at least the transmission in our test machine — which may not be typical: A lot of pressure was required to make shifts at high rev's. We missed a lot of gear changes until we learned to get a good, solid toe-hold and yank things into mesh. Fortunately, this reluctance to engage appeared only at the drag strip. In normal brush-basing usage there was no gear-change problem whatever.

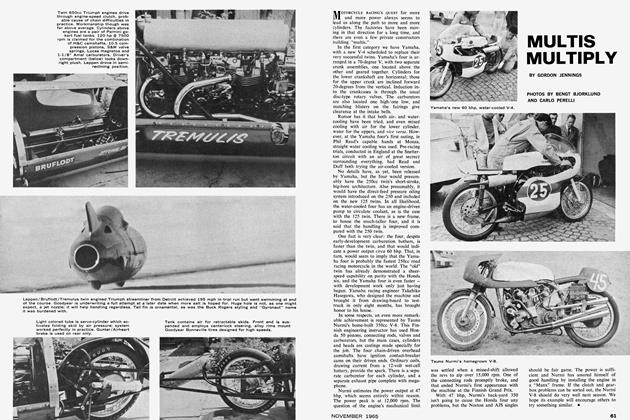

Along with the engine changes, relative to the 500cc scrambler, we have noted, the 650cc Spitfire has a slightly longer wheelbase. An extra two-inches of length in the rear suspension's swing-arm stretches the wheelbase from 54to 56-inches. We are informed that early versions of the Spitfire had the 500's wheelbase, and that the riders were adding the longer swingarm themselves. BSA, taking note of this, has made the modification standard. We noted no problem with the 500's handling at the time of our test, but it is possible that the bike becomes a bit twitchy with the added power from the 650 engine and the longer wheelbase tends to stabilize the situation.

In any case, the Spitfire Hornet does handle very well.

There is enough rake in the forks so that the bike will pick its way through the rough without a lot of wrestling and herding on the part of the rider, and the forks themselves have had their damping greatly improved over that provided in the not too distant past. The rear suspension can also be relied upon to behave itself, and while nothing as big as the Spitfire is ever going to be exactly agile, the rig is stable and a good rider can accomplish a lot of maneuvering with the right handlebar grip. Just bank it over a mite and turn up the wick; it will come around as though it had the wheelbase of a unicycle.

Get up close to the Spitfire, take a long, careful look and you will find a wealth of impressive small details. Like the exhaust pipes, which have a compound bend up at the cylinderhead (a difficult and expensive manufacturing problem) just to bring the pipes in close where they will not get banged against things. There was, unfortunately, a small problem with these pipes: at their rear mounting a spacer holds them cantilevered from a tab on the frame and vibration broke away one of the tabs on our test bike. Sad experience with other motorcycles with similar arrangements tells us that this will probably be a common occurrence. Perhaps a bonded-rubber mounting piece would ease the sharpness of the vibration enough to keep the tabs from cracking away.

We think the fiberglass fuel tank and "skirt" panels are a very good thing. Color is bonded-in, so they can't get all chipped, and they are light. The tank, having a 2-gallon capacity, gives quite a useful range, and it is fitted with a tap on each side. Yes there is a "reserve." The usual BSA single-bolt fastening is employed to secure the tank, with access to the bolt under a rubber dust-cap just behind the aluminum flip-top racing filler cap.

The seating position is excellent with a long, soft perch and pegs and bars set just right. In fact, the bike is fitted with a "buddy" seat, and would be great for packing double but for the lack of foot-rests for buddy. Still, the mounting lugs for passenger pegs are there. Buddy may have a bit of a problem with the exhaust pipes for although the pipes have heat-guards that, in theory, protect the rider's legs, these guards are a bit marginal for the rider and buddy would almost certainly collect some burns unless he wore asbestos boots.

Again, we will have to enter a complaint against British gravel-strainer air-cleaners, which the BSA and everything else from the Misty Isles seems to have. Once again, chaps: A) there is not always enough moisture in our air to keep the grit glued together in large, convenient clumps. B) the finely dispersed bits of grit will pass right through the sort of filters you universally favor. And C) the grit does terrible things to the inside of the engine. If we were at all inclined to be waspish, we could also mention that if there was much moisture in our air, the Spitfire's exposed electricals, located above the transmission casing and right in the line of fire of any mud and/or water from the rear wheel, will get more than somewhat wet.

On the other hand: three cheers for the accordiontype dust covers above the front fork's sliders, which would seem to promise a much extended life for the seals. More cheers for the effective stone/stump shield under the engine. We also liked the provision of two stands (one a side-prop; the other an over-center stand) on the machine, which serious competitors will promptly remove but which we found handy in casual sporting riding. And then there were the nice "eyes" on the handlebars for holding the control cables in out of the way. Finally, there was the ease of starting, a characteristic much appreciated by both racing and play-time riders. Total all this, and a lot of other little things too numerous for inclusion, and you have the BSA Spitfire Hornet, the friendliest firebreather of them all. •

BSA 650 SPITFIRE HORNET

$1182