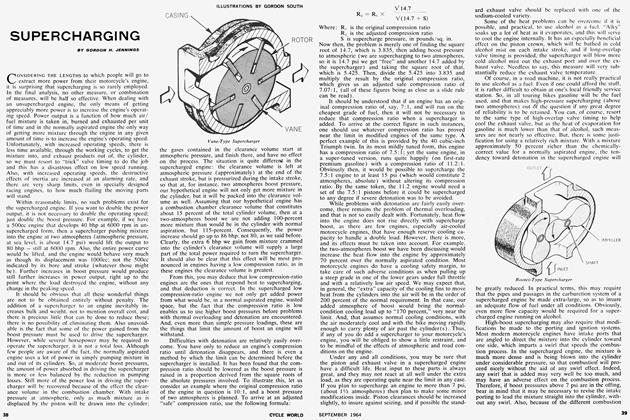

HONDA SUPER HAWK

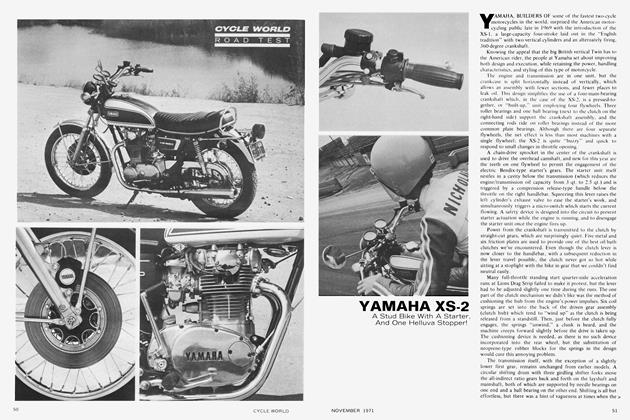

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

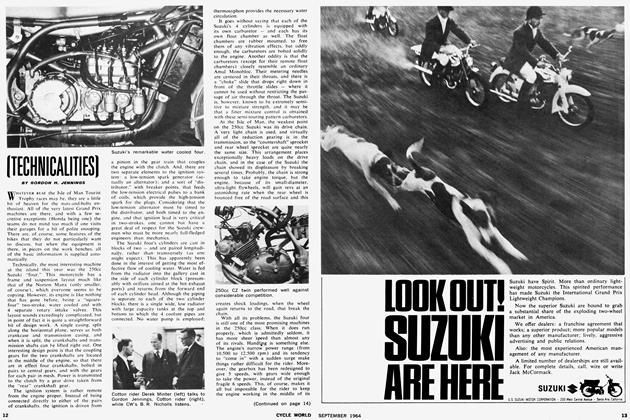

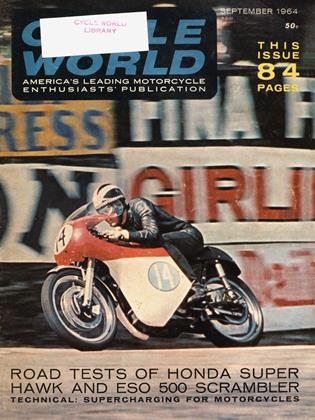

HONDA’S SUPER HAWK was one of the first motorcycles to be road tested by CYCLE WORLD (reported in the May, 1962 issue) and although the machine has been changed little since that time, we are repeating the test. The reasons: that we have acquired several new readers over the intervening years; and that the Super Hawk, changed or not, is one of the most advanced and best performing motorcycles available today. It will top 100 mph, climb to more than 80 mph from a standing start in a quarter-mile sprint, corner beautifully and stop on the proverbial dime — and it is smooth, quiet and starts with an effortless push of a button. In all, a very impressive motorcycle.

As we noted in our previous test, Honda’s racing experience shows in the design of the Super Hawk. Like the GP Hondas, the Hawk has a frame that gains much of its strength from being bolted solidly to the unit-constructed engine and transmission. In theory this makes the whole package lighter, and that may be the case, but there is no arguing the fact that it makes the task of removing the engine/transmission unit from the frame a lot easier. Also, it makes virtually every point on the engine accessible for quick service.

The Super Hawk’s engine/transmission unit was described briefly in our previous report, but a lack of specific information about the internals caused us to overlook a few points. As most of you already know, the Super Hawk engine is a vertical twin, constructed with a maximum use of light aluminum alloys, and having a single overhead camshaft. The overhead camshaft feature is not wasted, as the engine is “tuned” to produce maximum power at 9000 rpm — a peaking-point all but unknown in anything but pure racing engines until the Honda made its appearance. This very high peaking speed has not resulted in a drastic narrowing of the engine’s power range. Admittedly, there is a lot more power on tap when it is buzzing nicely than if the rider uses slogging tactics; but the engine begins to pull reasonably well at 3000-3500 rpm, and it pulls very strongly from 6000 rpm right up to the 9000 rpm power peak. Just past 9000 rpm, the valves begin to float badly, and it is valve float that limits the performance of the stock

Super Hawk — which may account for the popularity of racing valve spring kits made for the Honda. In our last report, we mentioned that the camshaft is driven by a single chain, located in a cast-in tunnel leading up between the cylinders. Chain lash is accompanied by a roller-type tensioner, with an externally-adjustable tensioner, and there is a guide roller to insure that the chain does not do anything unfriendly at high crank speeds. What we overlooked in the camshaft drive system was the automatic advance mechanism. Yes friends, there is a pair of centrifugal advance weights, just like those one might see in an ignition distributor, to advance the camshaft a few degrees as engine speed increases. This sounds rather exotic and exciting, but we suspect that this bit of apparatus was developed just to handle ignition advance, as the ignition breaker cam is located on the end of the camshaft. However, it may provide smoother low speed running to have the camshaft retarded. The advance mechanism, incidentally, starts pushing the valve and ignition timing ahead at 1100 rpm, which is just about idle for the Honda, and advances the timing a total of 40 degrees when the crank speed is at 3300 rpm — after which the timing remains constant.

Another design feature is the use of a cast-iron “skull” in the combustion chambers. These are cast into the cylinder head, and serve as valve seats for both intake and exhaust valves. And, the spark plug threads into this iron insert. By employing this arrangement, which does not take up space in the head for separate valve seat inserts, bigger valves can be used. There is also an obvious advantage in having the spark plugs threaded into iron, rather than soft aluminum.

Wet-sump lubrication is employed in the Honda engine, which eliminates external oil lines and a potential source of leaks. And, too, the fact that the crankcase is split on a horizontal, rather than vertical, plane will tend to prevent leaking. The same oil supply lubricates both engine and transmission (these are in the same case) and a small gear-type pump circulates the oil to both the crankshaft and transmission main shaft. Most of the bearings in the Honda engine are of the ball or roller type, including the

connecting rod bearings, and as these bearings arc rather sensitive to grit, a centrifugal oil cleaner is provided. This is a small drum, chain driven from the crankshaft, through which all of the oil to the engine bearings must pass. As oil moves through the filter, all dangerous foreign particles, being heavier than the oil itself, are caught by centrifugal force and packed into the rim of the filter. The owner's manual provided with the Super Hawk specifics that the filter be cleaned every 2000 miles.

Honda builds the Super Hawk as a sporting model, and this fact is very apparent in the bike’s brakes and suspension as well as in the engine. The brake drums, front and rear, are of fast-cooling aluminum, with cast-in iron liners, and have a diameter of almost 8-inches. The shoes are all “leading,” so there is a fairly strong self-servo action to the braking system that makes control pressures very light. The rear brake on the machine given us for this test was definitely weak, but we have ridden other Super Hawks and this weakness is not typical. In fact, the brakes arc so powerful that riders accustomed to machines less splendidly equipped for stopping will have to be careful not to apply too much pressure. It is quite possible to lock the wheels, if the surface is the least bit slippery, and that sort of thing will usually drop the motorcycle. With a little experience on the Super Hawk, one acquires finesse in applying the brakes, and then their very powerful and light action becomes a definite safety feature.

The suspension is quite conventional in layout, but it gives superior results. Both the springing and damping are somewhat stiffer than average, but they give a reasonably smooth ride, and very good road-holding. Honda engineers have provided quite good clearance under the machine, and it can be heeled over at a considerable angle before things begin to scrape; yet the handling is stable even when cornering with the pipes dragging the pavement. As a matter of interest, you might also be interested to know that the Super Hawk converts into a road-racing machine with very few changes, and it qualifies as one of the better handling bikes in that sort of use. To make the conversion, one has only to fit Honda’s option road racing springs, clip-on bars,

special seat, jets and megaphones. The foot pegs are repositioned higher and further back, which requires that a longer push-pull rod be made for the shift linkage. Finally, you can remove the lighting equipment and electric starter, just to save a few pounds, and the bike will be ready to go. Racing tires are good insurance on a bike set up in this’fashion: you will be able to go fast enough and lean far enough to make them worthwhile. The average Super Hawk buyer will be more than satisfied with the cornering capabilities of the stock machine, but we thought this information might be handy to anyone who might have some notions about going road racing.

The overall finish of the Honda Super Hawk is impressive. As one might expect in a machine that comes from the factory all but “untouched by human hands” (Honda’s manufacturing facilities are automated to a really fantastic extent), the bike has no hand-buffed surfaces, or indeed any evidence of hand-fitting anywhere. But, all of the components, large and small, have the appearance of having been made just for the job they are doing, and made to do the job very well. Everything fits, and everything looks good; it would be unreasonable, at anything near the Super Hawk’s selling price, to ask for more.

Now then; about the performance. We got a lot of static about the speed of the Super Hawk we tested in 1962; most of it to the effect that someone must have slipped us a super-tuned machine. Well friends, there have been times when we thought there was something in that charge; but not any longer. This last test machine was stock, and while its speed at the end of the standing-start VA -mile run was down by 1 mph, the elapsed time for the run (which is a better indication of acceleration ability) was shaved by two-tenths of a second. Thus, it seems that this performance is very close to what may be expected from any stock Super Hawk — and it is very good performance. The 1964 machine did suffer slightly more from valve float than the earlier test bike, but not enough to be significant.

And what does the buyer get besides performance and good handling and brakes and an electric starter? He gets a comfortable riding position, with a nice, soft seat and low, flat bars that lean him into the wind. He also gets a tool kit, complete right down to a pair of scissors, that will cover any sort of road-side repairs. And then there is the lighting system, which does an excellent job of illuminating the road ahead. And a speedometer and tachometer combined in a single instrument-head (both of which showed some error on the high side of the scale). And, last (except for the things we have forgotten) a vast network of dealers with parts and equipment to help the machine back to health when things go wrong. We find ourselves very much impressed, and wondering what, if anything, Honda will do for an encore? •

HONDA

CB 77 SUPER HAWK

$665

SPECI FICATIONS

PERFORMANCE

View Full Issue

View Full Issue