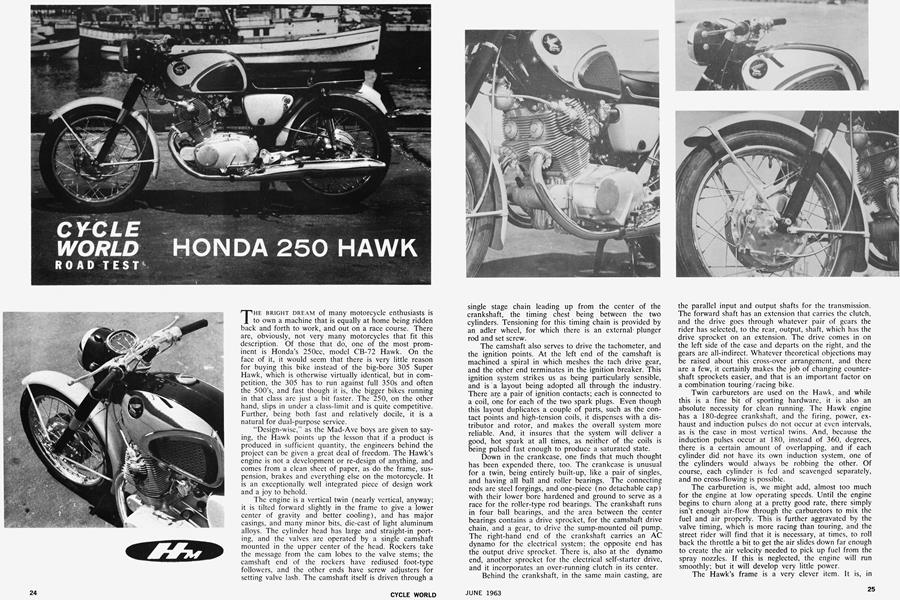

HONDA 250 HAWK

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

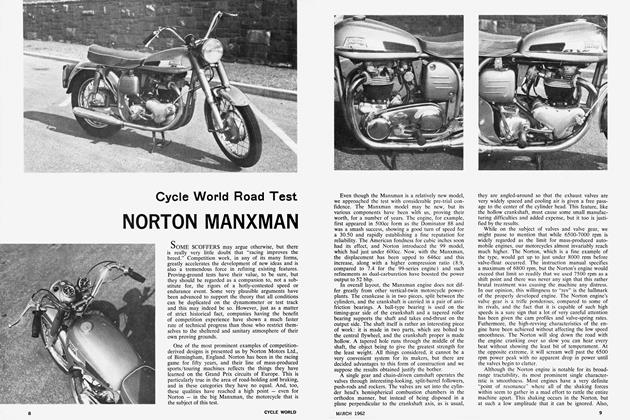

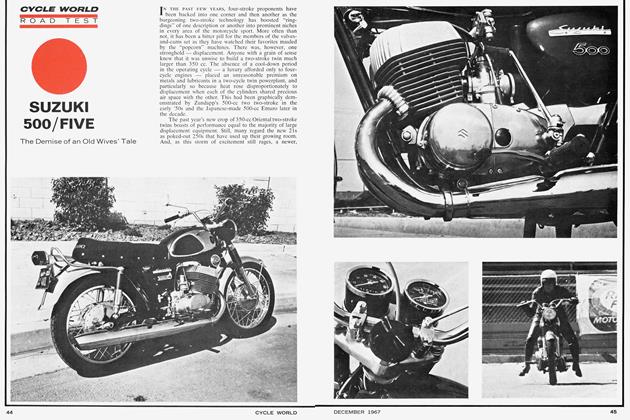

THE BRIGHT DREAM of many motorcycle enthusiasts is to own a machine that is equally at home being ridden back and forth to work, and out on a race course. There are, obviously, not very many motorcycles that fit this description. Of those that do, one of the most prominent is Honda's 250cc, model CB-72 Hawk. On the face of it, it would seem that there is very little reason for buying this bike instead of the big-bore 305 Super Hawk, which is otherwise virtually identical, but in competition, the 305 has to run against full 350s and often the 500's, and fast though it is, the bigger bikes running in that class arc just a bit faster. The 250, on the other hand, slips in under a class-limit and is quite competitive. Further, being both fast and relatively docile, it is a natural for dual-purpose service.

“Design-wise," as the Mad-Ave boys are given to saying, the Hawk points up the lesson that if a product is produced in sufficient quantity, the engineers behind the project can be given a great deal of freedom. The Hawk’s engine is not a development or re-design of anything, and comes from a clean sheet of paper, as do the frame, suspension, brakes and everything else on the motorcycle. It is an exceptionally well integrated piece of design work and a joy to behold.

The engine is a vertical twin (nearly vertical, anyway; it is tilted forward slightly in the frame to give a lower center of gravity and better cooling), and has major casings, and many minor bits, die-cast of light aluminum alloys. The cylinder head has large and straight-in porting, and the valves are operated by a single camshaft mounted in the upper center of the head. Rockers take the message from the cam lobes to the valve stems; the camshaft end of the rockers have rediused foot-type followers, and the other ends have screw adjusters for setting valve lash. The camshaft itself is driven through a single stage chain leading up from the center of the crankshaft, the timing chest being between the two cylinders. Tensioning for this timing chain is provided by an adler wheel, for which there is an externalplunger rod and set screw.

The camshaft also serves to drive the tachometer, and the ignition points. At the left end of the camshaft is machined a spiral in which meshes the tach drive gear, and the other end terminates in the ignition breaker. This ignition system strikes us as being particularly sensible, and is a layout being adopted all through the industry. There are a pair of ignition contacts; each is connected to a coil, one for each of the two spark plugs. Even though this layout duplicates a couple of parts, such as the contact points and high-tension coils, it dispenses with a distributor and rotor, and makes the overall system more reliable. And, it insures that the system will deliver a good, hot spark at all times, as neither of the coils is being pulsed fast enough to produce a saturated state.

Down in the crankcase, one finds that much thought has been expended there, too. The crankcase is unusual for a twin, being entirely built-up, like a pair of singles, and having all ball and roller bearings. The connecting rods arc steel forgings, and one-piece (no detachable cap) with their lower bore hardened and ground to serve as a race for the roller-type rod bearings. The crankshaft runs in four ball bearings, and the area between the center bearings contains a drive sprocket, for the camshaft drive chain, and a gear, to drive the sump-mounted oil pump. The right-hand end of the crankshaft carries an AC dynamo for the electrical system; the opposite end has the output drive sprocket. There is, also at the dynamo end, another sprocket for the electrical self-starter drive, and it incorporates an over-running clutch in its center.

Behind the crankshaft, in the same main casting, are the parallel input and output shafts for the transmission. The forward shaft has an extension that carries the clutch, and the drive goes through whatever pair of gears the rider has selected, to the rear, output, shaft, which has the drive sprocket on an extension. The drive comes in on the left side of the case and departs on the right, and the gears are all-indirect. Whatever theoretical objections may be raised about this cross-over arrangement, and there are a few, it certainly makes the job of changing countershaft sprockets easier, and that is an important factor on a combination touring/racing bike.

Twin carburetors are used on the Hawk, and while this is a fine bit of sporting hardware, it is also an absolute necessity for clean running. The Hawk engine has a 180-degree crankshaft, and the firing, power, exhaust and induction pulses do not occur at even intervals, as is the case in most vertical twins. And, because the induction pulses occur at 180, instead of 360, degrees, there is a certain amount of overlapping, and if each cylinder did not have its own induction system, one of the cylinders would always be robbing the other. Of course, each cylinder is fed and scavenged separately, and no cross-flowing is possible.

The carburetion is, we might add, almost too much for the engine at low operating speeds. Until the engine begins to churn along at a pretty good rate, there simply isn’t enough air-flow through the carburetors to mix the fuel and air properly. This is further aggravated by the valve timing, which is more racing than touring, and the street rider will find that it is necessary, at times, to roll back the throttle a bit to get the air slides down far enough to create the air velocity needed to pick up fuel from the spray nozzles. If this is neglected, the engine will run smoothly; but it will develop very little power.

The Hawk’s frame is a very clever item. It is, in effect, a single-loop frame, but the engine serves as the front and lower section of the frame. A single large tube leads back from the steering head, and then bends downward to pick up the rear of the crankshaft/transmission casing and rear suspension pivot. Also running down from the steering head are a pair of tubes that bolt to mounting lugs on the cylinder head. Tubular extensions fork away from the main structure to support the seat and carry the rear suspension’s spring/damper units.

As a sometime road-racing machine, the Hawk needs unusually powerful and fade-free brakes — and it has them. The drums are of aluminum, with iron liners, and finned, with a diameter of 8 inches. Both front and rear brakes have double leading shoes, and the way they pull

the machine to a stop is a source of great comfort to the rider. We tried the machine out in semi-road racing fashion, using the brakes very hard for an extended period, and they remained smooth and powerful for the duration of the testing.

Rider position on the Hawk is of necessity, because of the low, flat handlebars, very “Mike Hailwood,” and although it looks ferociously uncomfortable for touring, the controls and the seat arc positioned in such a way that it is, in fact, quite good. In any case, the combination makes the rider feel as though he is very much a part of the machine — and it is fun to drop into a crouch and bare your teeth at other riders as you go by.

Handling was just about what we have come to expect of a Honda: stable and fast-cornering. Fork angle, trail, spring rates and damper settings are near-perfect, and even a fairly timid rider will find it very natural to ride faster and lean over farther than it is his habit to do. We would want racing tires under the machine before getting too serious about competition, but even with the normal touring tires, this is an unusually fast-cornering motorcycle.

Performance was adversely affected by the comparative newness of the Hawk we were testing. A lot of miles were put behind the bike before we began flailing it really hard, but it was still a trifle tight when we ran out of time and had to complete our testing. Therefore, we would say that a Hawk fully broken in would come somewhat nearer the performance of the Super Hawk we tested last year (the report is in the May, 1962 issue of CYCLE WORLD). The 250 Hawk should run the standing-start VA -mile in about 17.3 seconds, and have a top speed of slightly over 90 mph; our bike was too stiff to come up to that standard.

There are, besides the items we have mentioned, a lot of minor things that make the Hawk attractive. The bike has an effective fiber-cartridge air-cleaner, and battery of sufficient capacity to cope with the extended winding-over and fiddling that cold-morning starting can entail. The saddle is wide and comfortable, ane one finds that the combination speedometer and tachometer cluster is a very sensible arrangement indeed — even though it is easy to get confused by the paired needles and small numbers at first. The finish is good, and the styling is really exceptional; the only criticism we have is that the Hawk is definitely on the weighty side for a 250 — but as it is just as fast as almost any other 250, one can’t grumble too much about that. In all, the CB-72 Hawk should be well nigh irresistible to the competition-inclined, pavement-type rider. •

HONDA CB-72 HAWK

$640.00,