The Fabulous VINCENT

The beginning, reign and decline of one of the most fantastic eras of motor cycling from which came some most remarkable machines, and an incredible heritage.

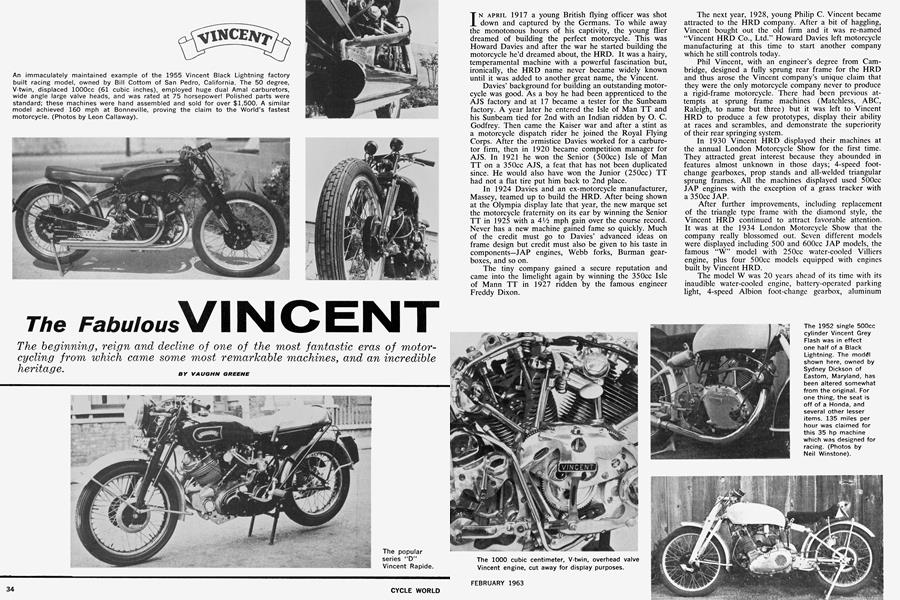

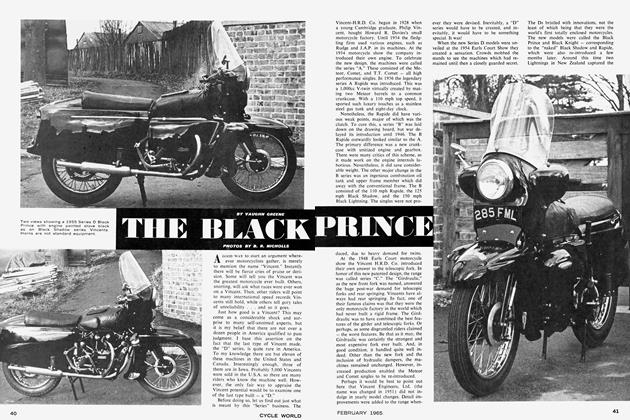

An immaculately maintained example of the 1955 Vincent Black Lightning factory built racing model, owned by Bill Cottom of San Pedro, California. The 50 degree, V-twin, displaced 1000cc (61 cubic inches), employed huge dual Amal carburetors, wide angle large valve heads, and was rated at 75 horsepower! Polished parts were standard; these machines were hand assembled and sold for over $1,500. A similar model achieved 160 mph at Bonneville, proving the claim to the World's fastest motorcycle.

VAUGHN GREENE

IN APRIL 1917 a young British flying officer was shot down and captured by the Germans. To while away the monotonous hours of his captivity, the young flier dreamed of building the perfect motorcycle. This was Howard Davies and after the war he started building the motorcycle he'd dreamed about, the HRD. It was a hairy, temperamental machine with a powerful fascination but, ironically, the HRD name never became widely known until it was added to another great name, the Vincent.

Davies' background for building an outstanding motorcycle was good. As a boy he had been apprenticed to the AJS factory and at 17 became a tester for the Sunbeam factory. A year later he entered the Isle of Man TT and his Sunbeam tied for 2nd with an Indian ridden by O. C. Godfrey. Then came the Kaiser war and after a stint as a motorcycle dispatch rider he joined the Royal Flying Corps. After the armistice Davies worked for a carburetor firm, then in 1920 became competition manager for AJS. In 1921 he won the Senior (500cc) Isle of Man TT on a 350cc AJS, a feat that has not been duplicated since. He would also have won the Junior (250cc) TT had not a flat tire put him back to 2nd place.

In 1924 Davies and an ex-motorcycle manufacturer, Massey, teamed up to build the HRD. After being shown at the Olympia display late that year, the new marque set the motorcycle fraternity on its ear by winning the Senior TT in 1925 with a 4½ mph gain over the course record. Never has a new machine gained fame so quickly. Much of the credit must go to Davies' advanced ideas on frame design but credit must also be given to his taste in components-JAP engines, Webb forks, Burman gearboxes, and so on.

The tiny company gained a secure reputation and came into the limelight again by winning the 350cc Isle of Mann TT in 1927 ridden by the famous engineer Freddy Dixon.

The next year, 1928, young Philip C. Vincent became attracted to the HRD company. After a bit of haggling, Vincent bought out the old firm and it was re-named "Vincent HRD Co., Ltd." Howard Davies left motorcycle manufacturing at this time to start another company which he still controls today.

Phil Vincent, with an engineer's degree from Cambridge, designed a fully sprung rear frame for the HRD and thus arose the Vincent company's unique claim that they were the only motorcycle company never to produce a rigid-frame motorcycle. There had been previous attempts at sprung frame machines (Matchless, ABC, Raleigh, to name but three) but it was left to Vincent HRD to produce a few prototypes, display their ability at races and scrambles, and demonstrate the superiority of their rear springing system.

In 1930 Vincent HRD displayed their machines at the annual London Motorcycle Show for the first time. They attracted great interest because they abounded in features almost unknown in those days; 4-speed footchange gearboxes, prop stands and all-welded triangular sprung frames. All the machines displayed used 500cc JAP engines with the exception of a grass tracker with a 350cc JAP.

After further improvements, including replacement of the triangle type frame with the diamond style, the Vincent HRD continued to attract favorable attention. It was at the 1934 London Motorcycle Show that the company really blossomed out. Seven different models were displayed including 500 and 600cc JAP models, the famous "W" model with 250cc water-cooled Villiers engine, plus four 500cc models equipped with engines built by Vincent HRD.

The model W was 20 years ahead of its time with its inaudible water-cooled engine, battery-operated parking light, 4-speed Albion foot-change gearbox, aluminum head, stainless steel radiator, fully enclosed engine and inconspicuous legshields. The result was weather protection for the rider and a motorcycle that could be ridden in any weather with only the tips of his shoes getting soiled.

Though several unusual machines were introduced, including a sidecar version with a radio transmitter, it was the brand new Vincent engine that attracted the most attention. This engine, so sound was the engineering involved, retained many of the same features until the last Vincent was produced in 1955. In fact, many of the parts in the first and last Vincent engines (valves, pistons, rods, chains, etc.) are interchangeable.

The chief designer, whose accomplishments were later to become legendary, was none other than P. E. Irving, author of Motorcycle Engineering and Tuning for Speed, two standard reference works in the motorcycle world.

This Series "A" Vincent engine is worth examining in detail. With a bore and stroke of 84 x 90mm (3.207 x 3.543 in.) the only difference in the original series and later engines was that the "A" had a 5-stud head while the later series used four through-bolts secured deeply in the massive alloy crankcase. Unusual features of the "A" included the quickly-detachable driveside main bearing, engine sprocket, magneto and oil pump. Twin valve guides were used to obtain cooler springs and the Series "A" used hairpin springs exposed directly to the air. A high camshaft wide-angle pushrod valve train was used, quite advanced for its day, and the rockers were forked to catch the valves. The rocker arm bearings were quickly detachable and the entire assembly could be pulled out by removing one bolt. This feature was retained on all later series, as was the 4-bearing lower end. A Burman gearbox was used and was interchangeable with postwar models.

Innovation did not stop with the engine. There were twin drum brakes (one on each side of the hub), the wheels were quickly detachable and, since the rear wheel had two drums, two sprockets could be carried. Thus, by reversing the wheel, the gearing could be altered in a minute. There was also lavish use of stainless steel in the new Vincent HRD; axles, brake rods, thumb nuts, motion blocks, gas tank, etc. A dream machine indeed.

The next year engines by other manufacturers were dropped with the exception of 20 special-order Model "W's" with the 250cc water-cooled Villiers. Through 1939 the Vincents remained essentially the same except for minor detail improvements. These models were the "Meteor" (25 hp, 75-80 mph, black and gold), "Comet" (26 hp, 85-90 mph, maroon and stainless steel tank), "Comet Special" (detuned racing engine in standard frame, 28 hp, 100 mph), and "Comet TT Replica" (bronze head, 34 hp, 110 mph).

In the 1935 Isle of Man Senior TT, Vincent HRDs took 7th, 9th, 11th, 12th and 13th places. Not bad for a standard touring machine that cost $800. In 1936, Jock West came in 8th, in spite of breaking a primary at the last minute. Zoller type superchargers were experimented with that year but there was too little time to work the bugs out.

The fabulous Vincent "Rapide" was first shown in October 1936. As a 61-cu. in. V-twin with 45 hp, a conservative 115 mph and weighing 400 lbs., it had nothing in the way of competition. The cylinder angle was 47 degrees and many of the parts were identical with the Vincent single. Weakness later corrected included the 4-speed Burman gearbox that wasn't up to holding the power fed into it and pushrods that wore very rapidly. The Rapide sold for $420 and another of the interesting features was the Smith's 8-day clock to match the 120 mph speedometer.

In 1937 Phil Irving returned to the Velocette factory, not to return to Vincent until the war when he became chief engineer to develop a special engine for airborne lifeboats.

In 1939, just before the war, Vincent announced a new series, the "B" range. Though only one "B" Comet TT Replica was built, it was a most interesting machine since the frame seemed to have disappeared. The front and rear forks bolted to the oil tank which was hidden by the encompassing gas tank. The engine was suspended from the oil tank member and appeared to be hanging in mid-air.

Like other manufacturers, Vincent HRD was engaged in war work during WW II. Because the plant was small it attracted little attention from enemy bombers and consequently, in April 1945, was the first English motorcycle manufacturer to announce a postwar machine. There was a tremendous response (some who ordered in 1945 had to wait two years for delivery) and the factory therefore decided to concentrate its production on Rapides.

The average motorcycle offered for sale in 1946-47 could only be described as miserable in both design and construction. Thus the Rapides became even more highly prized. Nor did the Vincent name go unnoticed in the U.S. Eugene Aucott, Philadelphia, became the first American Vincent dealer. Soon, Vincent H. Martin, Burbank, Calif., was also importing Vincents and the rush was on.

America had always been V-twin country and the odd-looking, ugly Vincent with its skinny tires and girder forks was immediately compared with the HarleyDavidson — thus creating a controversy that still goes on to this day.

The Vincent Series "B" Rapide which so startled the post-war world had a high-cam 50-degree V-twin all-alloy OHV engine with 4-speed unitized synchromesh gearbox. Aluminum alloys were used extensively; crankcase, cylinders, barrels, heads, hubs, shock absorbers, brake adjusters and so on. Unlike American practice, the Vincent used two male connecting rods which not only afforded interchangeability but also gave better cooling through the necessary lV^-in. offset of the cylinders. The liners were deeply spigoted into the crankcase, held in place by long bolts through the heads and attached to the head brackets. These in turn fastened directly to the box section oil tank and the effect was such a strong, vibrationless structure that no other support was needed for the engine.

The lower end assembly was massive. Three roller and one ball bearing supported the mainshaft and the nickel chrome steel rods ran on a casehardened crankpin and each was supported by three rows of uncaged roller bearings. The result was phenomenal bearing life. One Vincent, the famous "Rumplecrankshaft" of Tony Rose, was given a 100,000-mile road test without any apparent wear on the bearings and that same machine is still running with over a quarter-million miles on the clock.

The timing-side mainshaft drove the rotary plunger oil pump. The drive-side mainshaft was splined to accept an engine shock absorber. The materials throughout were the best available; the timing gear was aluminum, the pushrods silver steel, the pushrod tubes stainless steel, alloy rocker bearings, valve seats of aluminum bronze and austinitic cast iron, valves of DTD 49B steel and Silchrome steel, and so„on.

In the gearbox there was a beefy set of internals designed to transmit up to 200 hp and all shafts were supported by ball bearings. A weakness, if it can be called that under such conditions of abuse, showed up in America where lead-footed types stomped a too-weak cam plate bevel to death and this was replaced by a foolproof design in 1953. This bevel had more to do with losing sales for Vincent than any other factor since its replacement demanded that the entire engine be dismantled, which entailed removing the front and rear forks, exhaust pipes, magneto and generator, gas and oil tanks, and so on. Not that the riders lost interest. It was the dealers who rebelled, some stating that they were willing to sell Vincents but not to work on them or honor their guarantee.

Through this gearbox "weakness," another undeserved Vincent legend began. The actual fact is that the Vincent is a wonderfully easy machine to work on and, given anywhere near normal care, malfunctions are very rare. The clutch is an ideal case in point. Phil Vincent wanted that ideal, a dry plate clutch in a wetsump chain case. To achieve this, synthetic rubber seals were used. These seals wore in time, resulting in a slipping clutch as oil leaked in, but three-quarters of the trouble came from owners needlessly messing around with the clutch and gearbox housings. But who could blame them when that clutch-gearbox complex is so easy to dismantle?

The clutch, incidentally, consists of two clutches; a 2-shoe servo clutch and a single-plate clutch disc, and this results in an unusually light clutch lever action for such a powerful machine.

The Rapide framework also had many interesting features. All four brakes could be adjusted by hand from the saddle, both wheels could be removed without tools in less than a minute, the rear chain could be adjusted in a minute, the left and right prop stands could be swung down to make a front stand, and the oil tank contained a check valve so the oil would not run out if the lines were disconnected, very handy for overhauls. An experienced mechanic could completely dismantle a Vincent in an hour, including the lower end.

Other nice touches included hand-operated fittings to disconnect the wiring, raise the rear fender flap, and lower the rear stand. The battery could also be quickly removed by loosening a handwheel. It was also the first British machine to have dual "buddy" seats and there was a sliding tool tray under the saddle.

The rear brakes used a combination cable and rod system but the front, cableoperated brakes seem, at first glance, incapable of working. A single cable runs to a balance beam mounted on the front fork so when the handlebar lever is pulled exactly the same pressure is applied to each brake, thus equalizing any torque and greatly lessening the chance of a skid.

Other features include screen filters in the oil and gas lines and the famous short Vincent handlebars of 25-inches widtH All handlebar levers, the handlebar itself, the saddle, footrests and foot levers are individually adjustable.

A year after the introduction of the Rapide, the famous "Black Shadow" was first shown. Costing $200 more, it had a claimed cruising speed of 100 mph and a top of 125 mph. It had polished rods and rockers and lightened gearchange components, finned cast iron brakes instead of the pressed steel variety and a very gory-looking 150 mph 5-inch Smith's speedometer. The only concessions to speed were carburetors 1/16th of an inch larger and a slightly higher compression ratio. The entire engine was painted in black enamel to assist in heat dissipation.

Upon the heels of the Black Shadow came the "Lightning," the fastest racing motorcycle sold to the public. This sold for $1,500, had 70 hp and was rated at 150 mph. The Lightning was a stripped-down Shadow with aluminum wheel rims, magnesium brake plates, twin straight pipes, twin racing carbs, the compression ratio was to order and all stressed parts were polished and streamlined. Lightnings were put together by hand in a small shop and each was gently ridden for 100 miles on a test track and individually timed.

One of the first "B" Lightnings was owned by John Edgar, Los Angeles, and in 1948 veteran rider Rollie Free set a record of 160 mph with it at Bonneville. This was to start a round of record breaking at the Utah Salt Flats that still continues.

At the 1949 Earl's Court Show in London, the "C" range was introduced. These were essentially the same as the "B" except for a new front fork called the "Girdraulic." This was a combination of girder and telescopic fork with aluminum alloy blades made by Bristol Aircraft Co. It featured a hydraulic damper and selflubricating bronze bushes and is the strongest motorcycle fork ever made.

Also in 1949, the single-cylinder models were reintroduced; the Meteor, the Comet and the Grey Flash. The Meteor was a cheaper version of the $900 Comet and the Grey Flash was a racing model with 135 mph on 35 hp. A small number of speedway engines were also made. These were similar to the Grey Flash but with total loss oil systems and magnesium crankcases.

Speaking of speedway racing. Vincents dominated the tracks in Australia, where that sport is very popular. Vincents competed against Harleys, Indians, Excelsiors, double-engined Triumphs, JAPs and came off with the honors. In 1949, at Victoria, Tony McAlpine won every race he entered with his Shadow sidecar special.

Phil Vincent had assured John Edgar, owner of the "B" Lightning that had gone 160 mph, that the record should stand for 10 years. Only two years later, however, the same Rollie Free who had ridden for Edgar bought a "C" Black Lightning (as the "C" racers were known) and went 156 mph. In 1953, Joe Simpson, Stockton, Calif., upset the applecart with his "C" racer, one of the first sold in this country, and went 160 mph at Bonneville. Phil Irving was sufficiently impressed to ask Joe how he did it. As Joe put it, back in those days the British thought they were doing you a big favor by offering anything larger than a one-inch carburetor so, calling on his hot rod experience, he used bigger carbs, installed larger valves and so on. It was from Simpson's experience that the factory developed the famous ''Big Port" heads with carbs up to 1 9/16th-inch diameter.

Long before this, in 1948, the Vincent Owners Club* was started in England by Allan Jackson. It was, and still is, one of the most highly regarded clubs in England. The VOC has produced several reporters and an editor for the English motorcycle magazines and one woman member, Margaret Ward, is now secretary of BEMSEE. Rab Cook, a staff member of Motorcycling and former editor of MPH, the monthly VOC magazine, was one of the first to advise wearing crash helmets. The VOC started the custom of wearing helmets which soon spread throughout the world.

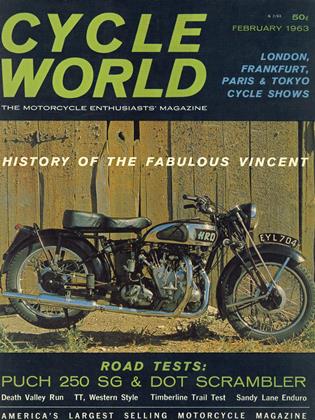

After the "C" series Vincent was introduced in 1950, they remained almost unchanged until the "D" appeared in 1954. The company's policy was to include improvements as soon as they were developed rather than indulge in the razzledazzle "brand new model" stuff every year, so the new "D" promised to be something special. And it was. It was the first standard motorcycle to offer complete streamlining in the form of a fiberglass shell. The motive was not increased speed or better fuel consumption, though these were improved, but to give complete weather protection to the rider. The fiberglass panels were quickly detachable by Dzus fasteners and the rear shell pivoted upwards to give access to the rear wheel. This rear shell also held the oil tank and there was a spacious tool box beneath the hinged saddle.

In these new models, the "Black Prince," "Black Knight" and "Victor" corresponded to the Black Shadow, Rapide and Comet models. The Series "D" Black Shadow and Rapide were naked models, without the streamlining, and were basically the same as the "C" version except for detail improvements. Coil ignition replaced the magneto, a center stand was introduced which was operated by a hand lever, larger tires and a fully-sprung saddle made for a much more comfortable ride.

Phil Irving was chief designer for these remarkable machines and the Vincent company was also building several types of small marine, agricultural and dairy machines. There was a cute little water scooter, a fuel-injected engine based on the Lightning for target drone aircraft, an unusual 3-wheel fiberglass car with standard Rapide engine and the firm also produced a very reliable little moped known as the "Firefly" which could run three miles on a penny's worth of gas. The name of the company was now "Vincent Engineers, Ltd.," the "Vincent HRD Co., Ltd.," having been changed in 1952.

It was against this background that New Zealanders Burns and Wright, using the "Big Port" heads, made their historic runs in February 1955 when Wright set a new world's record at 174 mph and Burns established a new world's sidecar mark at 162 mph. The next year Wright went 185.15 mph (not a record, but a 1-way run of 198 mph was achieved) and Burns upped the sidecar mark to 176.42.

It was indeed a shock then when Philip Vincent announced in the summer of 1955 that he would no longer manufacture motorcycles. For several years it had proven unprofitable; the big hairy machine was a thing of the past, felled by the 250cc motorbike. Knowledgeable riders flocked to put in last minute orders for the Vincents remaining. When the last of the 100 "D" Rapides was sold a total of 13,000 machines had left the factory.

The postwar history of the Vincent might be compared to a skyrocket. At first it was unknown, then it started to gain fame and rose in a rush. There was a time when it ruled over all, but the inevitable slump came, the descent, and then, the end. There were many reasons for this. Although the pre-war company supported works race teams, the later company concentrated on touring machines. The Vincents were also the most expensive motorcycles in the world at that time. Racing sells motorcycles and, naturally, the riders chose to buy cheaper machinery. Therefore, though the singles were as powerful as any OHV machines ever built, they were never too popular. The twins, though capable of tremendous power, suffered from heavy weight as compared to, say, a Manx Norton.

Although no longer manufacturing motorcycles, Phil Vincent promised that as long as a Vincent was still on the road, spare parts would be made. This is still true and it is easier to get parts for Vincents than many 1962 motorcycles. The Vincent company's troubles continued, however, finally going into receivership and was eventually bought by the Harper group of companies. After various troubles Harper Engines, Ltd., is enthusiastically doing repairs and making spares.

Will Vincents ever be made again? Most doubtful. Phil Vincent once said he would build 50 new engines only at $800 each. There was also a shop in England that was making "new" Vincents from spares and another fitted Vincent engines into Manx frames.

No, the gallant old V-twin is forgotten. Or is it? Clem Johnson recently turned 149 mph in the standing quarter on a Vincent. Dave Matson was building a 3engine Vincent to run at Bonneville before he was drafted. Joe Simpson owns the world's most powerful motorcycle, a 150 hp fuel-injected supercharged Black Lightning. George Brown recently set a new world's record for the standing kilometer on his famous "Nero." Simpson, and a handful of others, intend to capture the world's speed record soon.

The Vincent is fading away, having been out of production for more than seven years, but not nearly so fast as its competitors would like. Most often, the "fading away" is that of a black-engined motorcycle showing its license plate to a lesser machine. •

*For information about joining the Vincent Owners Club, write Vaughn M. Greene, P.O. Box 7724, Rincón Annex, San Francisco, Calif.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue