HARLEY-DAVIDSON 250 SPRINT

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

ONE of the curious things about the present-day motorcycle sales patterns is that a potential buyer, walking into a dealer’s showroom, may be interested in anything from a miniscule “tiddler” right on up to a big, powerful “brute.” In fact, the very same customer (gaining experience and enthusiasm) may return several times over the course of a few years to progress, in stages, from one of these extremes to the other. Obviously then, the dealer who doesn’t stock a full range of motorcycles (in size and price) is going to watch a lot of buyers take their business elsewhere. Understandably, this casts quite a pall on the profit picture, and anyone who wants to stay in business must, of necessity, offer a broad selection of machines.

The old-line firm of Harley-Davidson is not immune to this, nor are they unaware or unappreciative of what their dealers and customers want. Accordingly, they have been expanding their line of merchandise and today the buyer may have a spiffy scooter, no less than three featherweight “ring-dings”, a fast lightweight, a pair of sizzling-hot medium-heavies and, at the top of the line, the perennially-popular FL-series heavyweights which will go along at a very fast clip, also. We will, no doubt, get to all of these in due time, but our immediate concern is with the real newcomer, the Sprint 250.

Actually, the Sprint is an import, made in Italy by Aermacchi who are a subsidiary of Harley-Davidson. We really don't think it matters greatly where a motorcycle is made, but in this instance we mention it because the machine in question is so typically Italian.

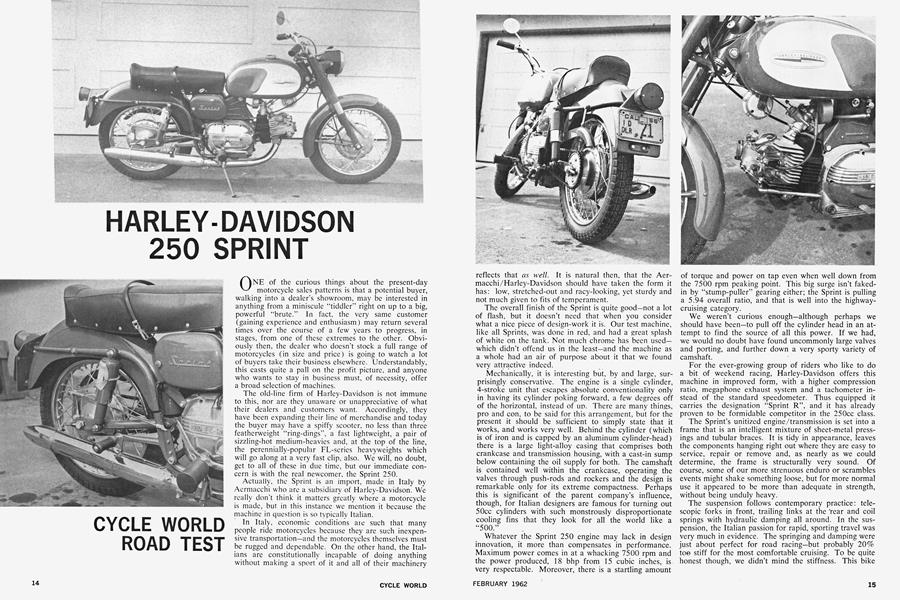

In Italy, economic conditions aie such that many people ride motorcycles because they are such inexpensive transportation—and the motorcycles themselves must be rugged and dependable. On the other hand, the Italians are constitutionally incapable of doing anything without making a sport of it and all of their machinery reflects that as well. It is natural then, that the Aermacchi/Harley-Davidson should have taken the form it has: low, stretched-out and racy-looking, yet sturdy and not much given to fits of temperament.

The overall finish of the Sprint is quite good—not a lot of flash, but it doesn’t need that when you consider what a nice piece of design-work it is. Our test machine, like all Sprints, was done in red, and had a great splash of white on the tank. Not much chrome has been used— which didn’t offend us in the least—and the machine as a whole had an air of purpose about it that we found very attractive indeed.

Mechanically, it is interesting but, by and large, surprisingly conservative. The engine is a single cylinder, 4-stroke unit that escapes absolute conventionality only in having its cylinder poking forward, a few degrees off of the horizontal, instead of up. There are many things, pro and con, to be said for this arrangement, but for the present it should be sufficient to simply state that it works, and works very well. Behind the cylinder (which is of iron and is capped by an aluminum cylinder-head) there is a large light-alloy casing that comprises both crankcase and transmission housing, with a cast-in sump below containing the oil supply for both. The camshaft is contained well within the crankcase, operating the valves through push-rods and rockers and the design is remarkable only for its extreme compactness. Perhaps this is significant of the parent company’s influence, though, for Italian designers are famous for turning out 50cc cylinders with such monstrously disproportionate cooling fins that they look for all the world like a “500.”

Whatever the Sprint 250 engine may lack in design innovation, it more than compensates in performance. Maximum power comes in at a whacking 7500 rpm and the power produced, 18 bhp from 15 cubic inches, is very respectable. Moreover, there is a startling amount of torque and power on tap even when well down from the 7500 rpm peaking point. This big surge isn’t fakedin by “stump-puller” gearing either; the Sprint is pulling a 5.94 overall ratio, and that is well into the highwaycruising category.

We weren’t curious enough—although perhaps we should have been—to pull off the cylinder head in an attempt to find the source of all this power. If we had, we would no doubt have found uncommonly large valves and porting, and further down a very sporty variety of camshaft.

For the ever-growing group of riders who like to do a bit of weekend racing, Harley-Davidson offers this machine in improved form, with a higher compression ratio, megaphone exhaust system and a tachometer instead of the standard speedometer. Thus equipped it carries the designation “Sprint R”, and it has already proven to be formidable competitor in the 250cc class.

The Sprint’s unitized engine/transmission is set into a frame that is an intelligent mixture of sheet-metal pressings and tubular braces. It is tidy in appearance, leaves the components hanging right out where they are easy to service, repair or remove and, as nearly as we could determine, the frame is structurally very sound. Of course, some of our more strenuous enduro or scrambles events might shake something loose, but for more normal use it appeared to be more than adequate in strength, without being unduly heavy.

The suspension follows contemporary practice: telescopic forks in front, trailing links at the 'rear and coil springs with hydraulic damping all around. In the suspension, the Italian passion for rapid, sporting travel was very much in evidence. The springing and damping were just about perfect for road racing—but probably 20% to© stiff for the most comfortable cruising. To be quite honest though, we didn’t mind the stiffness. This bike is designed for people who really enjoy going around corners with vigor and it is just the thing for that kind of activity. The Sprint is one motorcycle that needs nothing but the rider’s courage to get through the bends in fine, rapid fashion.

The positioning of the saddle, handlebars and footpegs invite this sort of fast riding. The bars are relatively low and flat, and the pegs are mounted well back, so the rider naturally assumes a crouch on the long, narrow saddle. All in all, it is simply too inviting a stance to resist. The final touch—which immediately caused us to head for our favorite twisting road—were the knee-notches in the sas tank. Usually, this kind of a feeling is the incubation period for a good case of “asphalt-rash”, but the Sprint’s excellent handling saved us that embarrassment and we were properly grateful for the favor.

At least the equal of the Sorint’s handling were its brakes, which are uncommonly large for so small a machine and which demonstrated a marvelous effectiveness through all of our testing. These are. like the rest of the bike, conventional in design and construction, yet give very superior results.

We did a fair amount of touring with this machine, and it displayed considerable merit in that category, too. As we stated earlier, the overall gearing is well suited to moderately fast highway cruising and the intermediate ratios are very useful traffic gears. Third gear, in particular, comes in very handy; it covers a speed range extending from barely more than a walk, right up to nearly 70 mph. In most instances, top gear could be used exclusively, the strong slogging-power of this small single being enough to cope with things. However, there were times when that long 3rd gear and a big handful of throttle were just what was needed and it was good to have it available.

Slightly less pleasing was the period of vibration encountered at 55 to 60 mph in top gear. All singles have these vibrations (as do most twins), but the Sprint’s buzzing occurred right at the speed we would like to have used for cruising. Dropping to 50 mph would have solved the problem, but we elected to go past the vibration point, and therefore spent much of our time cranking along at 65-70 mph. Even though this represented a steady engine speed of approximately 6500 rpm, there was no evidence that the Sprint was being unreasonably strained.

Another small complaint we have concerns the positioning of the kick-starter pedal on the left side of the machine, instead of on the customary right. Probably one would get accustomed to this after a time, but we didn’t care much for the arrangement and we were given plenty of practice, as the particular example we had for test was given to moments of sullen reluctance when asked to start. Actually, this hard-starting characteristic was probably not typical of all Sprints. Sometimes our test bike would fire right off, and other times it would be peevish and refuse to run. The trouble might have been some slight mechanical or electrical malfunction, or even faulty technique on our part.

The performance tests on the Sprint were a joy. This machine is fast enough to provide a lot of fun, and yet falls well below the point of being brutish. The clutch distinguished itself by giving a nice smooth engagement and when all the way home, gripped like Al Capp’s 10-day mule glue. The best results were obtained by cranking the engine speed up moderately high, then simultaneously easing in the clutch and winding on yet more throttle. Surprisingly, even though the Sprint is a small-displacement machine, it showed a marked tendency to lift the front wheel and all fast starts were made with some clearance between the front tire and the ground.

Harley-Davidson’s Sprint really is quite a bike. There is a suggestion of heaviness to the machine that many riders will find appealing (although it is not really heavy at all) and it appears to be, in every way, a thoroughly sturdy and reliable piece of transportation—and it has a substantial racing potential. And there is something to be said for the fact that it is being backed-up by the vast network of Harlev-Davidson dealers all over the country.

H-D 250 SPRINT

$695

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cycle Round Up

February 1962 -

The Service Department

February 1962 By Gordon H. Jennings -

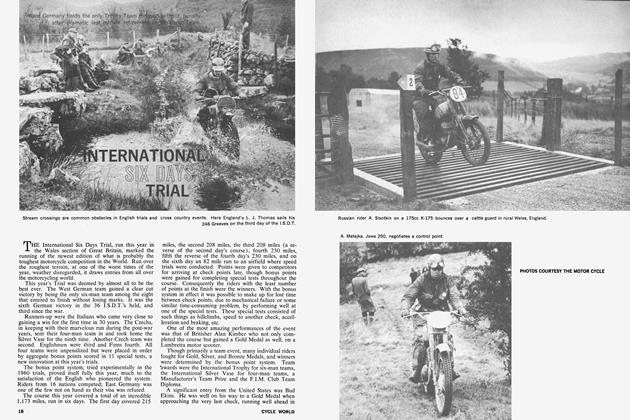

International Six Days Trial

February 1962 -

Technical

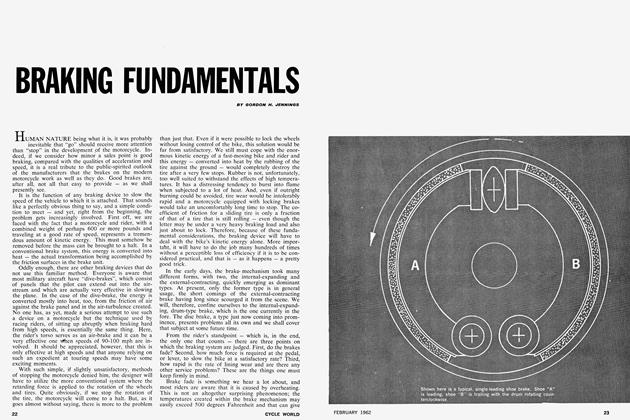

TechnicalBraking Fundamentals

February 1962 By Gordon H. Jennings -

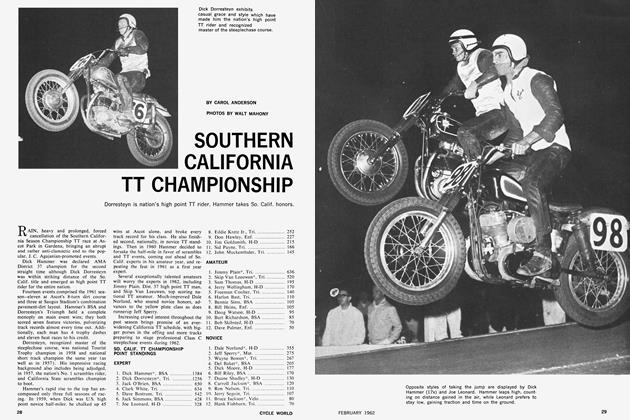

Southern California Tt Championship

February 1962 By Carol Anderson -

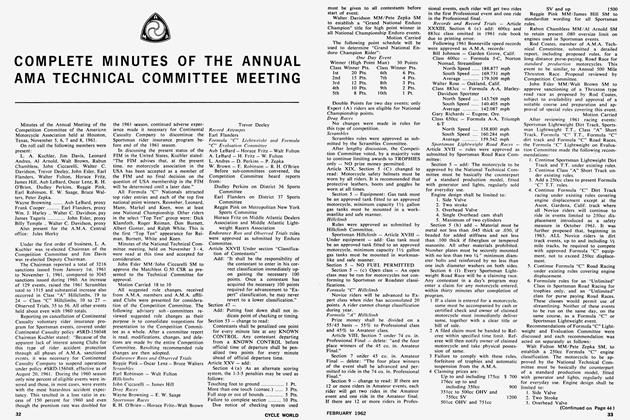

Complete Minutes of the Annual Ama Technical Committee Meeting

February 1962